In Wilfrid Sheed’s caustically hilarious 1970 novel, Max Jamison, the titular hero—the “dean of American critics,” as someone introduces him, and also a bit of a bastard—can’t shut down his brilliant critical instincts even when off the clock. When is a brilliant critic ever off the clock? He pans his wife (“God, he hated stupidity”), and lying awake at night, he pans his life (“The Max Jamison Story failed to grip this viewer. Frankly, I found the point eluding me again and again. The central character is miscast”). He disparages his looks (“Thinning hair might be all right but not

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

William Eggleston’s Democratic Forest begins with a single tree. Then, across ten volumes and more than a thousand photographs, we see a collective landscape, a vision that sweeps around the United States and overseas, through city centers and to the most forlorn edges of forest on a country road. But in the opening images, we are squarely in the American South, with an open ruin of a building, a gray storm waiting at the end of a road’s curve, the shell of a formal plantation house whose grand arcade has been overtaken by branches, neat crops stretching to a vanishing

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

We had a pleasant little party the other day, what can I say: tra-la-la, Aldanov in tails, Bunin in the vilest dinner-jacket, Khmara with a guitar and Kedrova, Ilyusha in such narrow trousers that his legs were like two black sausages, old, sweet Teffi—and all this in a revoltingly luxurious mansion . . . as we listened to the blind-drunk Khmara’s rather boorish ballads she kept saying: but my life is over! while Kedrova (a very sharp-eyed little actress whom Aldanov thinks a new Komissarzhevskaya) shamelessly begged me for a part. Why, of course, the most banal singing of

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

The reason we love a song usually has to do with longing: for a person, a time, a way of life. That is why my teenage songs have stuck by me. Back then, I did hardly anything but long. This yearning led me to doggedly pursue music and unreasonably identify with what I liked. Jonathan Lethem memorably described this phenomenon in his 2012 essay about the Talking Heads: “I might have wished to wear the album Fear of Music in place of my head so as to be more clearly seen by those around me.” This way of thinking might

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

Per publishing custom, the first pages of In Other Words, Jhumpa Lahiri’s fifth book and first essay collection, present a selection of critical praise for her previous work. The nature of this praise, all of it pertaining to Lahiri’s 2013 novel The Lowland, is both predictable and particular, with an emphasis on the author’s reputation as “an elegant stylist.” The blurbs celebrate Lahiri’s “legendarily smooth . . . prose style,” her “brilliant language,” and her ability to place “the perfect words in the perfect order.” Beyond the usual hosannas, what emerges is the sense of an author defined by her

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

A PARADOXICAL DILEMMA awaits the art restorer charged with repairing the damage done by time and mishap to an Alberto Burri painting, because his canvases were made by employing just those elements: aging, accident, and downright destruction. Trained as a doctor in his native Italy, Burri served as a medic during World War II, was captured in Tunisia, and was interned in a POW camp in Texas, which is where he began to paint. When he returned home, he found a culture beaten down by years of Fascist rule and a landscape blasted by Allied bombs. The ravages of war

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

“My true vocation is preparation for death.” That was the reply offered by polymath, scholar, filmmaker, archivist, and painter Harry Smith when asked what among his many pursuits he believed to be his “truest.” “For that day,” he continued, “I’ll lie on my bed and see my life go before my eyes.” If Smith’s declaration evokes the gnomic, ironic, dissolute, and fanciful, it also characterizes an artist who prized his own obscurity (and the obscurity of his myriad and often uncompleted endeavors) even within the more rarefied cultural circles of the postwar decades. The underground’s underground bard, Smith became famous

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

BETWEEN 1999 AND 2006, artist and musician Wynne Greenwood toured as the queer-feminist band Tracy + the Plastics. She performed live as front woman “Tracy” alongside other prerecorded, bewigged, and made-up selves: brunette “Nikki” (the “artistic” keyboard player) and blond “Cola” (the “political” drummer). Appearing on small TVs or in video projections behind her, the two virtual band members would harmonize, interrupt, and converse with her (and each other), creating a complex, layered set of performances. The group has now been both revived and archived in two exhibitions, for which present-day Greenwood refilmed the Tracy parts, performing with the original

- print • Feb/Mar 2016

The Los Angeles–based poet Melissa Broder writes about the hot-pink toxins inhaled every day by girls and women in a late-capitalist society (a few evocative phrases from her latest book: “diet ice cream,” “pancake ass,” “Botox flu”) and the seemingly impossible struggle to exhale something pure, maybe even eternal. “I tried to stuff a TV / in the hole where prayer grows,” she wrote in her pummeling 2012 collection, Meat Heart, which was followed by the searing Scarecrone in 2014. Here, from her website, is her version of an author’s bio: “when i was 19 i went thru a breakup,

- print • Apr/May 2016

I don’t care how much your parents fucking loved you—you’ve got problems. Me, I was abused by an alcoholic father, molested by a neighbor, kidnapped and raped at fifteen, so my PTSD is like a fungus with more PTSD mushrooming on top of it. I go to therapy to tell all these crazy stories over and over till they become just stories. Like a house that grows smaller and smaller out the back window of a car. Luckily, I’m a musician, so I can also write songs about this stuff. I can’t tell you how powerful it is to write

- print • Apr/May 2016

The protagonist of Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7 conjures the material for two hours of plot by getting her cards read in anticipation of a call from her doctor. “I can’t see you yet,” the tarot reader says to the distraught, beautiful woman. “The cards speak better if you appear.” Madame Irma reshuffles the deck after laying out a series of foreboding cards, claiming they are “difficult to read.” Fearful and impatient, having purchased enough portents for one afternoon—“The illness is upon you”; “I see evil forces. A doctor”—Cléo aborts the reading and soon bursts into tears. At

- print • Apr/May 2016

Scene: the kitchen table in Diana Abu-Jaber’s grad-school apartment. It’s 1986 and she’s making pad thai as she and her friend Liza discuss a) the militant women’s-studies reading group that recently invited Abu-Jaber to a meeting only to disparage both the story she just published in a literary magazine and the food she brought along; and b) Abu-Jaber’s newfound and financially expedient side gig as an author of “adult” novels.

- print • Apr/May 2016

THE WORLD OF CHARLES AND RAY EAMES (Barbican Art Gallery/Rizzoli, $75), with a dust jacket that folds out into a colorful poster in the image-grid style the design duo popularized, may seem like an Eames lounger: Something you can settle into and use to travel back in time to, say, 1956. But don’t get too comfortable. This catalogue is not about midcentury modern furniture and decor, but instead shows how the Eameses communicated their rationalist vision of design: a way to provide “the best for the most for the least,” as they often put it. Even their famous Pacific Palisades

- print • Apr/May 2016

“If Elvis Presley is / King,” Amiri Baraka’s “In the Funk World” asked, “Who is James Brown, / God?” This, as far as black people throughout the world are concerned, is not a question but an assertion. “You want to say Elvis was King? Feel free,” we might say. “But he never ruled us!”

- print • Apr/May 2016

“I WANTED,” Marcel Broodthaers declared in his 1954 poem “Adieu, police!,” “to be an organ player / in the army of silence / but played hopscotch / on the pink dew of blood.” Either choice—each one an irresistibly visualized paradox—gives vivid testimony to the multifarious career of this Belgian artist who began as a poet and (after encasing fifty of his unsold volumes in plaster) became a sculptor, collagist, painter, filmmaker, and all-around provocateur who parodied the institutional qualities of a museum by creating one of his own in his Brussels studio. With strong roots in Surrealist subversion, his comically

- print • Apr/May 2016

The first essay of Geoff Dyer’s new collection, White Sands, features the perpetually unsatisfied author on a junket to Tahiti. He’s supposed to be writing about Gauguin, whose famous painting Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? gives the piece its title, but—and this will be no surprise to readers of Dyer—he winds up writing about writing about Gauguin. Turns out tropical paradise is no paradise. The trip may be free, but it sure ain’t fun. The food is bad and overpriced; the view from the hotel is compromised; the monuments are just dumb rocks.

- print • Apr/May 2016

Mark Twain was at the peak of his fame when a London club granted him an honorary membership. Told his only predecessors were two explorers and the Prince of Wales, he sized up his own inclusion nicely: “Well, it must make the Prince feel pretty fine.” The planet’s most celebrated American author until Ernest Hemingway came along—and guess whose laurels have proved more durable?—Samuel Clemens was never one to take a backseat to anybody. No wonder, then, that he seems much more himself as the undisputed star of Chasing the Last Laugh, Richard Zacks’s entertaining account of the international lecture

- print • Apr/May 2016

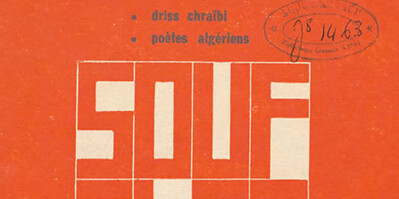

The great Moroccan writer Abdellatif Laâbi was just twenty-three years old when he met the poets and painters who would help him revolutionize the worlds of art, literature, and politics across North Africa and the Middle East. It was 1965, and Morocco was poised between a once-promising independence, which it had won from France nine years earlier (only to see it diminished by the restored monarchy’s crackdown on dissent), and the “years of lead” (zaman al-rasas), which would stretch into four decades of increasingly brutal repression under the reign of King Hassan II. It was also the height of the

- print • Apr/May 2016

MY COPY of Raymond Pettibon’s mammoth new anthology of drawings, Homo Americanus: Collected Works, sat untended atop a week’s worth of review copies until I took a good look at its cover. The image is a classic Pettibon, save for a few flourishes of watercolor: It shows a mohawked, guitar-wielding SoCal punk rocker of 1980s vintage, sporting a rainbow-colored Black Flag T-shirt. But on closer inspection, I realized that the appendage caressing the ax’s neck isn’t the punk’s left hand at all—it is, instead, an enormous erect penis. Since there’s a thirteen-year-old girl in my house, I smuggled the book

- print • Apr/May 2016

Sarah Bakewell’s previous book, published six years ago, told the story of two lives: the one Michel de Montaigne lived in sixteenth-century France, and the one that became “the long party” attended by everyone who read him over the years after his death. The party was an intimate affair because Montaigne often seemed to know us better than we know ourselves, and certainly expressed many of our thoughts better than we do. Bakewell’s new book, At the Existentialist Café, has the same double motion. It recounts the lives of the writers and philosophers who hung out at that literal or