He climbed to the top of the tree. The freight still passed, its many-colored, many-shaped cars looking like the curious shapes of a puzzle.

Down the road Layton saw his grandmother coming. Beside her walked Mrs. Fields, who lived in the cabin with her ailing husband and his mother, Granny Lincoln. Nobody knew how old Granny Lincoln was except Granpa Fields. He claimed that his mother was born a slave and when she was a girl had seen Abraham Lincoln campaigning for the presidency. The two old women wore wide straw hats, which cast long boatlike shadows in front of them. Their aprons bulged with vegetables as they approached in the dust, an ancient silence walking beside them, a part of them, and yet, like them, a part of the land.

Leaning out from the tree with his feet firmly set in the notch where the limb sprung from the body of the tree, and holding to the neck of the tree with his left hand, Layton raised his right hand at the train. How many times had he waved at trains? If he could live as long as the number of times he had waved, he knew, without counting them, that he would live to be as old or older than Granny Lincoln. But there was something about waving at a freight train that seemed dry and meaningless. He lowered his hand. He had always waved at the swift passenger trains, and many times when he went across the river and sat by the tracks, people on the train would wave back. He never knew if the white faces waving at him would ever make the engineer stop the train for him. His brother had ridden on a train when he had gone off to Vietnam. But that was two years ago and his brother had been killed over there. They said he had been missing in action. He thought of himself in a few years riding on a train or maybe even an airplane and being a soldier somewhere. He would fight in his brother’s place. He would save up all his money and come back to New York, give it all to his mother to help her. Yes, he would do all that and then he would buy a car, come back to Holly Springs and take his grandmother to Illinois where his uncle Joe lived. Uncle Joe had said that he wanted her to stay with him, but she had always refused.

Layton watched the last car on the freight. The hot white dust clung to the smooth hard surfaces of the tree like powder.

Long before the cement factory was built several miles down the road, Layton had fallen from the tree, but it had been because he was careless. Now with the dust from the trucks and cars and the factory, all the trees and shacks in Holly Springs took on the look of the blight. Granny Bridges called it the blight. It had come with the bauxite mines years before and now it had spread over the land like a creeping fever. A dry fever. One that made you sneeze, cough and choke. It killed the trees, the grass and gardens. There were certain vegetables that his grandmother could not grow anymore. Something about the land refused the seed, as if the land was sick, and didn’t know any longer what its nature was.

Once he recalled, when Granny Lincoln was brought out to sun, some big trucks loaded with ores stopped in front of the house. The men had heard about some sweet water around somewhere in the area and wanted some. Granny Lincoln had wanted to know what the men were doing carrying away her yard, and when Granpa Fields tried to console her, she refused to listen. Finally she had taken consolation in the Bible, saying that all of those trucks and men were signs. She said it was written that in the latter days, Satan and his angels would come forth from the earth seeking whom they might devour.

He began to climb down, the deadly powder making his descent as treacherous as his ascent. He had seen no sign of life on the freight. He had only shaken white dust into the air. It was a three-o’clock afternoon sun, hot, direct, lapping at the wounded earth with a dry merciless tongue. Layton did not feel angry at the sun, not really. He had learned somewhere in school that the sun was the source of all power. It was the sun that made the gardens grow, made the fields of hay, and cotton, corn and sorghum. It was the sun that drew up the rain from the ocean and sent rain down to make things green. Yet he knew it was by some terrible agreement, something beyond his comprehension, that allowed the sun and the whitemen to weaken the land. It was the same feeling which took his joy away when he thought of his coming new life in New York. It was like waving at a freight train. Somewhere he felt betrayed. Perhaps he was betraying the land himself. He felt that it all was a part of a great conspiracy . . . with the sun in the center. He did not like to think of leaving her to the mercy of the heat and the dust. And yet . . .

The only thing that gave Layton any real consolation was the fact that his grandmother was indestructible. He watched her slow pace up the road, her blue apron bulging with vegetables she had gotten from Granny Fields. She would sit on the porch in the evenings and the white dust never settled on her. Sometimes, he would think, gwine live forever. . . .

The two old women entered the bald yard in front of the shack. Their heads were bent as if they were watching the direction of their shadows, but Layton felt instinctively that his grandmother knew that he was in the tree. She never had to look at things to recognize them.

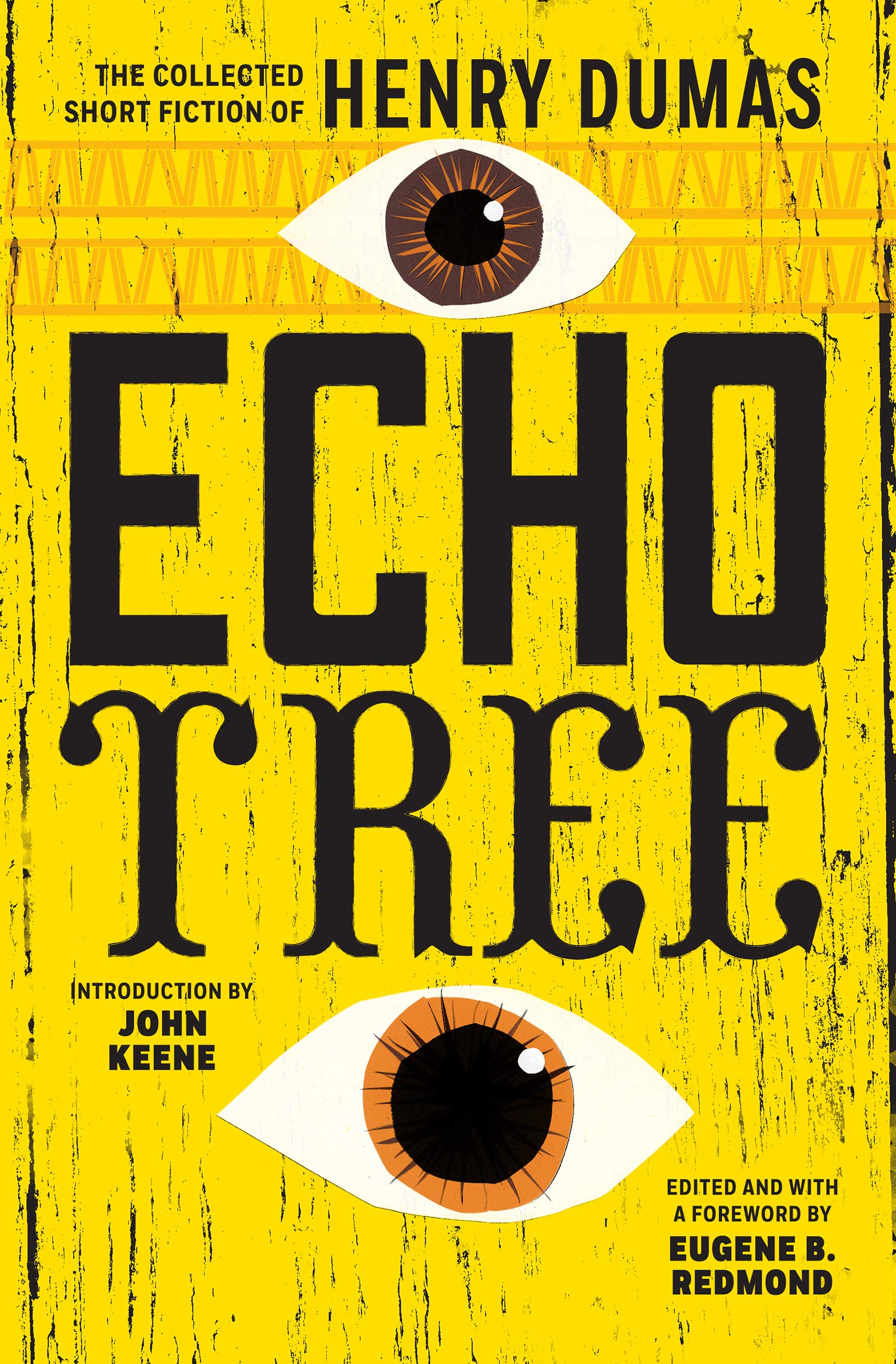

Used by permission from Echo Tree: Collected Short Fiction (Coffee House Press, 2021). Copyright © 2003 by the Estate of Henry Dumas