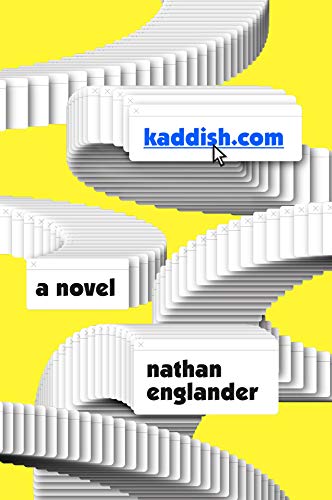

There is an oft-quoted line from the Talmud: “And whoever saves a life from Israel, the Scripture considers it as if he has saved an entire world.” Nathan Englander’s latest novel, Kaddish.com, is centered on a son’s preoccupation with saving his father’s soul—not for this world, but for Olam HaBa, or the World to Come. The novel is the Pulitzer Prize finalist’s most humorous and moving work since his best-selling debut collection, For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. Divided into four parts, Kaddish.com follows its protagonist’s transition, from secular, single, cynical Larry to devoted husband, father, and Yeshiva teacher Reb Shuli.

More than twenty years ago, Englander went through a similar, if reversed, transformation: Raised in an orthodox Jewish household, Englander as an adult became an avowed atheist. His writing reveals the frictions between these two versions of the Jewish-American experience—the plots of his books often hinge on bifurcations, secrets, and ghosts. But Englander’s concerns move beyond those specific to his upbringing by focusing on larger questions about the permeable borders of modernity and tradition, morality and immorality, believers and non-believers, individuals and families—definitive themes in American literature of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. While the basic story of his latest novel is well-charted territory for Englander, Kaddish.com does not feel like a hollow repetition. This is because Englander has added a new element to the binaries he explored his earlier works: how the emptiness we encounter in this world is magnified by the terror we feel about the unknown in the next.

The novel begins with Larry, a firmly secular Jew, mourning his father’s death at his religious sister Dina’s Memphis home. Larry is out of place among a pious, observant congregation. It’s not just discomfort he feels among them and their rigid rules for mourning, but a kind of suffocation that leads to despair. On the final evening of shivah, his sister reminds him of his obligation as the only son to recite the Kaddish for their father for the next eleven months. To say that she is worried is an understatement. But for Dina, the recitation of Kaddish is not about being religious or believing. It is about fulfilling a duty, as mechanically and methodically as possible. “You can think nothing and feel nothing and eat your cheeseburgers every meal,” she tells Larry. “But you can’t skip a minyan. Not once. Not ever. It’s what our father expects—what he expects right now from Olam HaBa.”

Larry responds with his trademark tragic humor: “Why does everyone keep acting like I’m not Jewish? . . . You think I don’t know the rules? You think, without you watching, I’d cremate him and stuff his ashes in a can? That I’d plant his bones in some field of crosses and pour a bottle of bourbon on the mound?” As we get to know Larry, we understand that he struggles less with belief than with the almost obsessive nature of following those beliefs. For Larry, to believe in Jewish law is to be committed fervently, deeply, and literally to rules that must be followed in order to secure the “best conditions in the World to Come.” To not do so would be cataclysmic—a paralyzing thought.

Sitting alone in his nephew’s room, Larry reels from the week-long ascetism—no drinking, no smoking, no masturbating—and finally turns to the forbidden internet for some relief. How, Larry wonders, can he find someone to “say the Kaddish in his stead?” He finds the answer in kaddish.com, a website devoted to connecting Jews with rabbinical students who are “the perfect match for the fallen.” It was, as Larry notes happily, “like a JDate for the dead.” A Yeshiva student named Chemi takes over the burden, praying for Larry’s father three times a day for the next year.

Englander is a master at displaying the way a single decision, made in a private moment, can stay with us for the rest of our lives and haunt our future. The remainder of the novel is devoted to the aftermath of Larry’s choice to shirk the most important duty to his beloved father, “white bearded and full of faith . . . who saw his true nature, loving Larry for exactly who he was and cherishing the man he’d become.”

Rather than follow Larry’s “transformation,” we instead jump forward in time, meeting Larry just as the secret of his father’s kaddish begins to unravel. Twenty years after his father’s death, Larry has become Reb Shuli, an Orthodox Jew and middle school Yeshiva teacher, now married to a pious and practical woman, Miri. Shuli, who recites his “‘lost soul’ narrative” at every Shabbat dinner and any other occasion to inspire his wayward students, loves his devoted wife and his two young children. All seems to be well, until Gavriel, a young student who has just lost his father, finds himself in Reb Shuli’s office. Echoing the revelatory figure of Gabriel in the Book of Daniel, Gavriel resurrects Shuli’s greatest urge: to track down Chemi and regain his birthright to pray for his father. The journey takes Shuli back to his past, and also back into the world of forbidden modernity for religious Jews, and to Jerusalem, the contested homeland. With this new journey, Englander plays with the traditional redemption narrative—Shuli was once lost, and twenty years later, he is even more so.

During this quest, his father appears in his dreams, ephemeral and tender, closer and farther than ever. Shuli’s wife Miri, who exasperatedly learns about his mishaps as she observes his increasing erratic and anxious behaviors, asks him to confront his grief and stress by visiting a therapist or taking pills. Shuli, however, seeks a more spiritual solution. “You and I have dedicated our lives to saving Jewish souls,” he tells his wife. “What about saving mine?” Miri begs him to reconsider his mission. “After all the good you’ve done, you think for one youthful mistake God will call back your soul?” she asks. “You really believe that’s how Heavenly justice works?” But for Shuli, it’s not about feigning innocence—he can lie to everyone, but he knows that he and God will forever know the truth. “If I’d acted out of ignorance, then no,” he tells her. “But even then I knew better. Even then, I was already not so young.”

Shuli’s spectacular belief in God’s “life-threateningly real” judgment is part of what separates him from the other believers, who seem to approach the rituals and laws in Jewish life with the same rigidity, but never seem to rise above the level of performance. In some ways, Shuli’s commitment and fervor to belief is naïve. But in his dedication to this quest, as well as his previous refusal to live by these religious rules, Shuli shows an admirable level of devotion, a refusal to do anything half way. For Shuli, to live in this world is to also pave one’s way in the world to come; as he tells a proprietor in a Jerusalem shop whom he promises to pay back, “Debts, in this world, I no longer let sit.”

Leah Mirakhor is a writer. She teaches at Yale University.