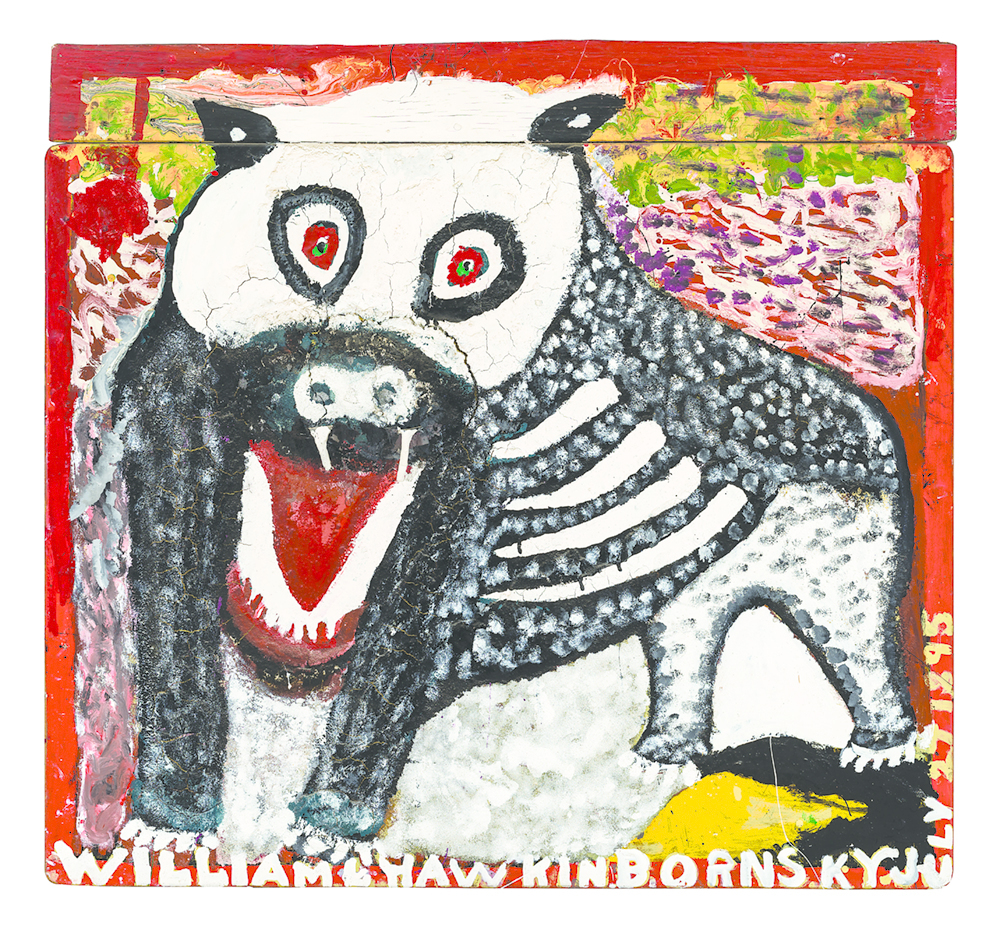

William L. Hawkins painted a near-encyclopedic array of subjects: animals both familiar and exotic, the Last Supper, cityscapes, stadiums, winter landscapes, Old West scenes, a bullfight, a jukebox, Jerusalem, the Statue of Liberty, the Nativity, the moon landing, and the rock of Gibraltar. Hawkins was a longtime resident of Columbus, Ohio, but his vision extends to distant locales, taking in everything from Bible history to Mr. T. On almost every one of his paintings you will find his date and place of birth (“William L. Hawkins Born KY July 27, 1895” or some variant thereof) prominently marked in assertive strokes across the bottom or along the side of the image. The lettering is as energetically declarative as his depictions: a snake and an eagle in battle, a charging rhino, a rearing horse—even the state office tower in Columbus—all pulsate as if they might burst across the edges of the Masonite board on which they’re painted. These works have a rough, garage-made quality, as he often used hardware-store enamels, thickly applied, as well as sand, gravel, cornmeal, found objects, and newspaper clippings.

and plywood, 443⁄8 × 473⁄4".

Hawkins drove a truck for a living well into his eighties; before that, he ran numbers, ran a brothel, and served in the army. He was an inveterate collector of odds and ends, many of which he repurposed in his imagery, drawing on magazines such as National Geographic and Smithsonian and books like The Golden Book of America for source material. The very definition of a self-taught artist (“I’m nothing but a junk man,” he once told Gary Schwindler, who contributed an informative essay to this volume), he instinctively understood the role of the outlandish, cast-off, and commonplace in the creation of the mythic. In a series of several Last Supper paintings, Hawkins varied his treatment of the iconic figures, sometimes using strangely askew, collage cutouts to render Christ’s eyes, or replacing his face entirely with that of Stevie Wonder. Even the food gets a witty twist: Platters of spaghetti and meatballs, pizza, and Jell-O have been inserted to make for a tastier meal than the usual Passover fare. In a painting titled Founding Fathers, those familiar faces—Washington, Jefferson, et al.—have been colored super-white, their mouths filled with jagged teeth to monstrous effect, and each has been given a bow tie and what could be a bellhop’s red jacket.

Hawkins’s animals read as both fearsome and endearing. The wide and childishly eager gaze of Tasmanian Tiger #2, 1986 (above) softens the appearance of its gaping red maw, calling to mind a panting puppy rather than a devouring beast. Eyes, incongruous or exaggerated, are often set to mischievous effect. The bull in Charging Bull with Matador #1 appears to prance rather than charge, and its collaged, quite feminine eye seems about to wink seductively. In Hawkins’s art, the signifiers fly every which way, into and past one another. His color-rich domain is carnivalesque, a locale where the fantastic jostles cheerfully with the quotidian.