It is a misconception that witch hunts only occurred during the Middle Ages—many took place during the alleged lucidity of the Renaissance. Men exploited the climate of suspicion to dispose of women they didn’t want around. Whole family lines were wiped out. Nonconforming women were denounced, humiliated, and killed. Centuries later, this kind of persecution continues in insidious ways, underpinned by relentless misogyny and victim blaming. The same female figures are still considered dangerous: the single woman, the childless woman, the aging woman—all dismissed with fear, pity, or horror.

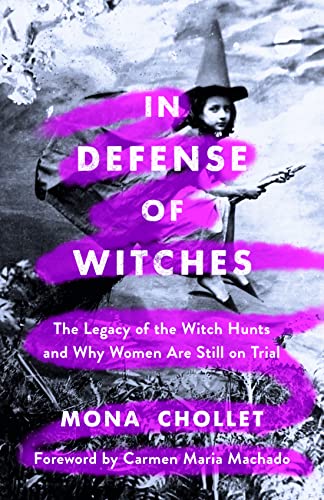

This is the premise of Mona Chollet’s In Defense of Witches: The Legacy of the Witch Hunts and Why Women Are Still on Trial (translated by Sophie R. Lewis): the indictment of modern women is tethered to archaic conceptions formulated in the fifteenth century. Swiss-French author Chollet has spent fifteen years as an editor at the monthly French newspaper Le Monde diplomatique, covering international politics and economics. In 2017, she took a sabbatical to write In Defense of Witches, drawing from writers, sociologists, philosophers, pop culture, and conversations with friends: prismatic ways by which to examine the witch as a timeless symbol of female insolence, independence, and perpetual subjugation. I recently met with Chollet, who discussed overturning the witch’s symbolism, the commodification of despised women, and her own reluctant feminism.

SARAH MOROZ: What was your starting point for this book?

MONA CHOLLET: I wanted to write about child-free women and aging women. I couldn’t decide between the two subjects, and neither was satisfying on its own. Then I thought, I could write a book about women who are not socially accepted. I realized that both these kinds of women are, in their own way, witches. Single women are perceived as a threat to society. I started to read about witch hunts, which really continue today. They don’t take the same form, but there is still a feeling of suspicion—single women worry people. It’s a relief when a woman is tied to a man. I went back and forth between the witch hunts of yesteryear and the circumstances of today, showing how certain “types” of women—definitions forged in the fifteenth century—are still considered dangerous. I wanted to write about all the situations in which the figure of the witch is embodied, maybe not even on a conscious level. A woman who’s aging, who’s single, who doesn’t have kids—she awakens something threatening, or is disapproved of. She’s not explicitly treated like a witch, but the past gave us an interpretive framework for this figure that still applies. We see an old woman and automatically reject her. I think there’s a historically informed dimension to that, and these definitions still shape the ways in which women are detested.

In her foreword to your book, Carmen Maria Machado writes, “like so many things capitalism touches, [the witch] is in danger of dissociating from her radical roots. What could have once gotten a woman killed is now available for purchase at Urban Outfitters.” This is something you allude to in your text, too: “witchcraft is also an aesthetic, a fashion . . . and a lucrative money-spinner.” How do you wrestle with this misappropriation of such a charged historical figure?

There’s an interesting movement of salvaging the figure of the witch—overturning the stigma and the pejorative associations. There’s this twisting of her into a powerful figure when, in fact, she was very vulnerable, targeted as weak and incapable of defending herself. She was tortured and killed. There was no victory at the time—witches were powerful only in the imaginations of the people persecuting them. She has been recast and valorized: that’s a good thing but, of course, there’s the spiral into commercialism. As women, we still need to be reminded of our strength, so it’s not surprising that there is a market for merchandise.

Did you hope to reach a particular audience with this work? And did the book’s reception in France surprise you?

I had no precise intention, but I was really struck by the fact that we haven’t granted the proper weight to this period. I think there’s an enormous heritage that explains a lot about the way women feel about womanhood and about how we’re treated. Doing this work helped me realize an ultimately simple thing: even when we talk about the single lady with her cat today, there’s an obvious trace of the witch with her familiar, the chat diabolique.

I was also writing about topics that were very personal. When you work on something close to who you are and your own needs, people are touched by that. Things in which you felt really alone suddenly become shared. As for the reception, based on events in bookstores, it was always young women who were attending and who told me the book had changed things for them.

Did you get a response from men too?

I know a few men who read it, but when I was doing book signings, men were asking me to sign the book for their girlfriend/sister/mother/daughter. They weren’t going to read it. It’s not new or surprising that men don’t read many books written by women—even less so when they’re focused on women-specific subjects—but it’s frustrating. Because men live with women, they should be interested in their experiences.

You draw clear parallels between an antiquated culture of suspicion and modern-day considerations of nonconforming women. Given this stubborn persistence of certain gendered attitudes, how do we change the narrative?

I’m almost fifty, and over the course of my adult life, the evolution has already been amazing. I grew up in a world where feminists were just a few strange women, always mad, and not to be trusted. Feminism was so unpopular. Now, it’s extraordinary the way young women behave—they don’t want to please men at all costs—and I admire that very much. I was raised to please men and be an “acceptable” woman, to not be angry, or too demanding. I see how young women push that, and push men to evolve and understand things about them. This social blackmail—that if you’re not a “nice” girl, you’ll never be loved—today, they don’t care! My hope is that men will be forced to evolve and be interested in women’s experiences. But it’s a big struggle. In France, I’m really struck by the violent reaction against this. Many men are resisting this evolution with all their strength, because they’ve been living in a world that is so comfortable. It’s really about including your experience of the other in your vision of the world. And many men are not willing to do that.

In the book, you admit to your own timidity with feminism. You call it poule mouillée feminism or the “‘scaredy-cat’ branch of feminism.” You write: “I stick my head above the parapet solely when I can do nothing else, when my convictions and aspirations force me to. I write books like this one to boost my courage.” Can you expand on this?

I was raised in the 1980s and it was such a conservative time. Women were not supposed to be bold. But I became a feminist anyway because I needed to. It’s mostly related to the fact that I wanted to write. And when you write, you become very threatening to men. You feel you are transgressing. As a young journalist, too, it was not easy to work at newspapers because men were always outnumbering us and were always in positions of power. There was a future where women weren’t welcome. And then there’s the fact that I never wanted to be a mother. So, I had no choice. I had to embrace feminism. Of course, it’s a good thing. I wanted to insist on the fact, though, that I was afraid, and I’m still afraid. I think it’s good to be honest about it. We can’t always be strong and confident. It’s not easy—it has a social cost. But not being a feminist also has a social cost.

Is there a specific threat underpinning the fear?

There are a lot of consequences: harassment online and even among family. It’s very violent to be called ugly or crazy or both, to be threatened with rape or murder. But maybe it’s also a fear of not being the “nice girl” that I was raised to be. There’s a great French philosopher, Manon Garcia, who wrote We Are Not Born Submissive: How Patriarchy Shapes Women’s Lives. She talks about submission and the advantages it has had—and that’s a good analysis. There are women who defend the social order as it is. For them, it’s a better bet. You saw what we call the tribune Deneuve? [In January 2018, one hundred high-profile French women, including actress Catherine Deneuve, denounced #MeToo as “going too far” in the French newspapers, including Le Monde and the left-leaning Libération.]

Yeah, ugh, I saw that.

Of course, I was sorry to read that. But I think it translates an attitude. It’s like what Andrea Dworkin wrote about right-wing women—some women chose to be on the side of patriarchy, because they feel they gain from it. They don’t want to fight all the time, to go against the tide.

If you were always a “nice girl,” who or what helped you transition into being less “nice”?

It was cumulative experience that brought me out of it. The injustice of being a woman moved me. I read Susan Faludi’s Backlash at a young age, right when it was published—it wowed me. I was helped along by reading.

Sarah Moroz is an arts and culture journalist who has written for The Cut, the New York Times, The Guardian, and other publications.