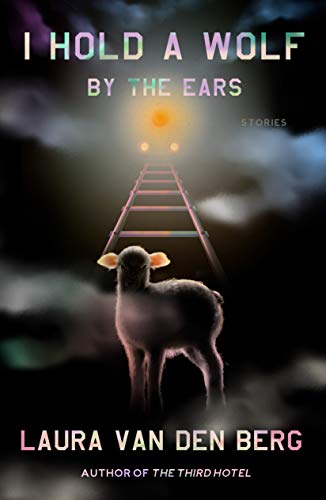

Laura van den Berg writes ghost stories: In her new book, I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, absences assume a life of their own, demanding to be acknowledged. The dead, the forgotten, and the lost have a shimmering vibrancy, becoming more present than the real. Like her ghostly figures, van den Berg comes home in this collection. Short stories were her first literary love, and I Hold a Wolf by the Ears is her return to the form after two successful novels.

The book also represents a more literal homecoming. Van den Berg’s stories traverse the world, but almost always weave their way back to Florida, her home state. It’s partly Florida that she credits for her work’s strange, “saturated” quality, its uncompromising expansiveness and otherworldliness: “I needed to be able to open this portal and climb into the sky,” she told me.

Bookforum spoke with van den Berg about the American South, the weird existence of the business traveler, and the difference between writing about the gig economy and working in it.

Most stories in this collection don’t take place in Florida, but they all bear some connection to the place. In recent years, there’s been a flow of art about Florida, as well as a kind of memeified version of the state. What makes it such good fodder for fiction and art?

I grew up and went to college in Florida, so I’ve spent more than half my life here. There’s no question that it’s been the most formative place for me. I profiled an artist named Beverly Acha, who is from Miami, and she talked about how when she went to art school in New England, people would ask her: “Why is everything so saturated?” And it took her a while to understand that the palette of this place was formative for her. I’ve had a similar experience. When I was doing my MFA everyone was like, “Why is everyone so weird!” And I didn’t think everyone was weird! I thought I was writing realism!

It’s also worth saying that Florida is worlds stacked upon worlds, with significant differences in culture, demographics, and weather. Literature from Florida is finally starting to reflect the diversity of the state. When it comes to the memeification of Florida, this gets flattened into caricature. That’s where the writers and artists come in—we tell stories that are more complete than these caricatures. We’re perhaps compelled by the saturation, the strangeness, an overall feeling of precariousness—especially as climate change becomes more and more of an emergency.

Do you think of yourself as part of a tradition of Floridian or Southern art?

Yeah, I totally do now. I resisted that for so long because when I left here, I had in my mind that the North is where things happen. Ideally New York, but Boston is acceptable. I was very eager to shed my Florida-ness, which, of course, only asserted itself in my work all the more. There was something about visiting in short increments and allowing myself to see, over time, what an interesting, endlessly complex place this is. I also have a more expansive concept of the American South than I did previously. My mom is from Nashville, and she was always like, “This is not the South.” It took me a while to understand that what she meant was, “This is not the South of my childhood.” But, of course, the American South is much more expansive than any one person’s definition of it.

This idea of visiting a place to gain perspective makes me think about the role that tourism plays in your book. Your characters visit Iceland and Mexico and Italy, and I’m curious about how tourism can serve a work of fiction.

Being from the Orlando area, travel literature with all its attendant flaws and complications, has always been interesting to me—that question of, “How are places narrated by an outsider?” I’m also interested in characters traveling for work, because that is a very specific kind of liminality. You’re like a tourist with a job, which is true of the narrator of “Karolina,” the story that’s set in Mexico City. I’m interested in the ways in which the positionality of the traveler can complicate the access that they have, choose to have, or choose not to have in the place they’re moving through.

In stories like “Volcano House” a lot of the travel takes place on organized tours. What is it about these experiences that you find helpful in building a story?

One very simple way to think of fiction is as different contexts colliding. A tour, from the outside, appears to have one perspective. But really, there are myriad contexts within the context of the tour. You have this group of strangers, they are traveling together, they are eating together, they are presumably staying in the same hotels, so there’s a kind of intimacy to it and also a real anonymity. And I think that that sort of friction, that contrast, that countercharge is super interesting. In “Cult of Mary”—the story about the mother and daughter touring Italy—the tour appears to be a united front. But you have the perspective of the guide and different political perspectives among the travelers.

“Cult of Mary” delves into politics, but, like a lot of these stories, it straddles the line between the very contemporary and the otherworldly. The story “Lizards” portrays a version of the Kavanaugh hearings alongside an almost supernatural haunting plot. Which events have drawn you to engage with these more political themes?

Certainly “Lizards” came out of the Kavanaugh hearings. I kept writing a scene where a husband and wife were washing dishes and watching the hearing, and I could never get past that. And then I got this idea that he was sedating her with a La Croix–like seltzer, and I was like, “No! That’s too weird!” But the more I thought about it the more I was like, “That’s maybe just weird enough.” I needed to be able to open this portal and climb into the sky with the introduction of the sedative seltzer.

In that story, and also in “Karolina,” I was thinking about the role that white women played in the 2016 election. The husband is the villain in “Lizards,” but the wife character, while a victim, is also just relieved to be able to switch off her brain. She’s really angry about the Kavanaugh figure. But what is she willing to give up in the service of dismantling the structures that make a person like Kavanaugh possible? Maybe not that much.

A lot of your characters, including the husband in “Lizards”—whose day job is waiting in lines—are exhausted by the demands of the gig economy. What kind of opportunities for character-building do you think arise from gig work?

There were drafts of the story where the husband had no characteristics other than being a closet Kavanaugh supporter who was drugging his wife. And to show him in contexts where he’s capable, and questioning, and in pain, and humiliated, just suggests a broader range of humanity for him.

The character in “Your Second Wife” is most comfortable in her gig of impersonating dead wives for bereaved husbands. She’s comfortable performing someone else’s identity, in a very defined context with lots of rules and restrictions. And she is compelled to think about what it means that she is so good at this job that allows her to stay in a constant state of performance—to not ever have to engage with her own self and her own regrets and her own desires. And on the one hand, there’s a kind of precarious freedom in it. But, of course, in the real world, people are not gigging because they’re trying to escape their own selfhood, it’s an economic model that we’ve found ourselves mired in.

I want to stay on this idea of women impersonating one another for a minute. There are so many instances in this collection of women assuming other women’s identities. How do you conceive of this relationship between femininity and ghostliness?

In this collection, I was really interested in writing woman-to-woman relationships. This would often concern two women kind of colliding in some way, or an absence creating a kind of presence. I think of that as being one of the fundamentals of haunting. An absence—a death—creates its own kind of presence, and that presence has its own consequences, its own complexities. And so, in “Volcano House,” for example, you have two sisters. One is a shooting victim and is in a coma, and one has kind of moved in with her brother-in-law to oversee her sister’s care. The more time she spends with him, the more they adopt marital rhythms. There’s deep love between these sisters, but they weren’t very close before the shooting. So, the narrator is not even mourning her sister’s imminent death as much as she’s mourning the relationship that they will never have. She’s mourning the absences that just can’t be filled.

I want to close by asking you about the title story and title phrase, “I Hold a Wolf by the Ears.” What does the phrase mean to you, and what is its relationship to the other stories in the collection?

Well, one thing that I hope the women in this collection are doing for each other in some of the stories is providing alternate models of ways to be in the world. And, in that way, they become sort of their own portal, where the narrator is able to look through the window of this other person and see a new path.

But all of these stories concern situations that are irresolvable—partially because of the emotional material, partly because the problems the characters are wrestling with are both personal and structural. That phrase, “I Hold a Wolf by the Ears,” is like, you’ve gained some sort of control over the situation, but how do you move forward? The wolf can still probably shake its head and then bite your hand off or it’s going to be unsustainable to keep holding the wolf by the ears. Someone’s gonna get tired eventually. These characters have found a tenuous way to live in a deeply imperfect world, and when the events of the story implode their coping mechanisms, they have to find another path.

Eleanor Stern is a writer based in Eastern Europe.