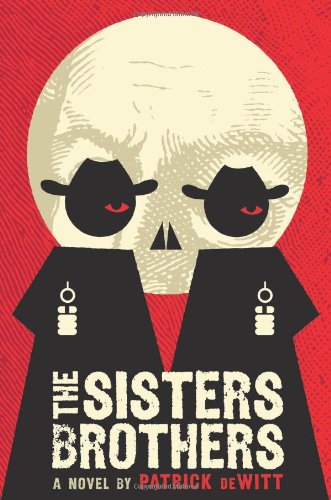

In 2009, Ablutions: Notes for a Novel introduced author Patrick DeWitt as a master of corrosive comedy. That book follows a barback at an L.A. watering hole who, with alarming (and somehow hilarious) alacrity, ruins his marriage, robs his employers, and calls in a bomb threat during a shift. For all of its chaotic scenes and drunken antics, DeWitt’s debut proceeded with a raconteur’s wit and surprising control, qualities that also distinguish his follow-up, The Sisters Brothers, released this week. The new book is a Western, but it, too, is about a job of sorts: Siblings Eli and Charlie Sisters are professional killers employed by a mysterious crime boss known as the Commodore. They travel from Oregon to California on a mission to kill a man named Hermann Kermit Warm for reasons that are for most of the book unclear. Along the way, Eli, the narrator and the sweeter of the two killers, bickers with Charlie, falls in love with a hotel prostitute, and relates his misadventures with droll restraint and a sense of wonder. Bookforum recently asked DeWitt about living with ghosts, his attraction to Westerns, and the sad undertones of brotherly love.

Your protagonists are morally problematic. In Ablutions the main character engages in all sorts of quasi-sociopathic behavior. In The Sisters Brothers, the two main characters are professional killers. And yet they’re so charming, for lack of a better word.

There’s a hurdle to clear when your protagonist is unlikable in terms of who they are and what they do, but obviously I wanted the reader to root for both Eli and the bar-back protagonist from Ablutions, even if it was against their (the reader’s) better judgment. The way to accomplish this, I decided, was for the protagonists’ core unhappiness to be relatable to the layman, and also for the protagonists to possess something like charisma, or as you say, charm, because we’re so much more forgiving of a person when he’s entertaining.

Both of your books feature characters who feel trapped by the work they do. At the same time, these characters’ jobs provide the context in which they achieve some sort of independence. Did you see similarities in how the bar-back in Ablutions and Eli Sisters in the new novel find their freedom?

There’s a link, yes, an intentional one. The work theme of Ablutions was under-discussed in reviews, but for me that was one of the focal points of the story. The book starts when the job starts, and ends when it ends. And it’s the same, basically, with The Sisters Brothers. I’m not a lazy person, but from the first shift of my first job I simply loathed working. It represented nothing more than a freeze frame in terms of my improving as a writer. I resented this, but was also frightened by it. This has stayed with me, I guess.

What drew you to write a Western?

It started out as a bit of vague dialogue, and if you’d told me it would become my second book I would have been very confused and probably a little worried, too. What happened was Eli got to me. And then Charlie got to me. And then that whole world got to me, and my goose was cooked.

One thing that’s different about the books is that in The Sisters Brothers, Eli strives for some kind of human connection, although it’s usually hard to come by. He and his brother love one another, but they can’t quite express it. At one point, Eli tenderly holds a man’s hand, but that hand has been chopped off.

The constipated male-bonding theme! There’s something so sad about that chopped off hand part; it chokes me up a little. But yeah, this phenomenon is interesting to me, when men can’t tell men that they care about each other. And then when they finally spill the beans, it doesn’t even feel good, it just kind of hurts.

Both of your books have these isolated unreal moments—ghosts, hexes, dream sequences. There’s a ghost in Ablutions. And there’s a witch in the new book, who casts a spell that prevents Eli from leaving a particular house—at least for a while. How do these fantastic scenes interact with the rest of what seems to be a fairly realistic novel?

The supernatural or magical parts were more prominent in an earlier draft of The Sisters Brothers, but I cut them back drastically to make way for the brothers’ relationship, and for Eli’s relationship with the world. I didn’t like the idea of removing those parts entirely, so it was a question of finding a more modest place for them. I decided to go the spare route, to the point that most of those story lines eventually vanish or dead end. I lived in a haunted house for a while, and my roommates and I were harassed by the ghost. She’d sit on our chests when we slept and we’d wake up gasping for air. As unpleasant as this was, our lives didn’t revolve around it. It was just another thing to worry about, along the lines of making rent. This phase was something I referred to in my mind when I was deciding how and where to position the supernatural elements in the book.

You leave a lot of motives and emotions unexplained. In three different episodes, for instance, we encounter a man who is sobbing so hard he cannot speak; he is referred to as “the weeping man.” Most novelists would probably explain why he is sad, but you pointedly don’t.

You know, all these things are just weighing each character out against the larger story. It’s not something I approach intellectually or with any plan in mind—they’re instinctive decisions. I seem to have an affinity for veiled scenarios and veiled characters, and I seem to prefer the open-ended to the fully explained, but I don’t consider the why of it; it’s just my natural inclination. I mean, I couldn’t care less why the weeping man is weeping! It literally never occurred to me to investigate. His function is to weep, nothing more.

I remember when Ablutions came out, hearing back from some people who felt that what was missing was the protagonist’s back story—the explanation of why he was the way he was. And I couldn’t think of something I had less interest in exploring. It’d be like doing homework.

The Sisters Brothers is (along with Ablutions ) one of the funniest books I’ve read in a long time. A lot of the comedy is fueled by imagination—how far can you take a scenario? But I think it also has something to do with your syntax. How much do you find comedy through style?

Maybe not style so much as rhythm, I think. Timing, rather than the content—rather than what’s being said. Comic writing is something I arrived at the long way around. In the years I was trying to figure out how to write I felt a kinship with—I guess you would call them unhappy authors. And it was a given that I would write unhappy books. So it came as a surprise to me, and not a particularly welcome one, that I had any kind of aptitude for comic writing. I didn’t want to make people laugh. I wanted to make people die! And I had this notion that humorous writing was secondary to the other urge, which is idiotic. Obviously I’ve come to embrace it, though the humor’s usually tempered with something fairly nasty.

Chance plays a significant role in your novels. What role does luck play in your fiction?

There’s a line in A Streetcar Named Desire where Stanley Kowalski says: “You know what luck is? Luck is believing you’re lucky, that’s all . . . To hold a front position in this rat-race, you’ve got to believe you are lucky.” That sums up a minor theme that runs throughout The Sisters Brothers, echoed by both Eli and the Commodore, and I guess it’s a sentiment I’ve taken to heart. It sounds a little brutal, doesn’t it? But, I do think there’s something to it.

How do you think you’d fare in the world you portray in The Sisters Brothers?

Are you calling me a pussy?

No, of course not! You obviously know how to adapt to various situations, at least as a writer. I hear that you’re working on screenplays as well as novels.

I wrote the screenplay for a film called Terri that will be released in June or July. Azazel Jacobs directed it and also helped with the story. Going in, I had a concern that the constraints of the format would be a pain, but I really enjoyed doing it, and I imagine there’s more screenplay work down the road for me. But I’ll always go for the novel or short story over anything else. Right now I’m working on a new novel about a corrupt investment banker who expatriates to France to avoid imprisonment. It’s in that dizzying phase where the scenarios materialize and I need to figure out where to put them. I know he’s going to go to an autopsy in Paris. I know he’s going to get plastic surgery. I’m pretty sure he’s going to get a hand job on a senior-singles cruise. This is the fun part, the part I’ll forget a year from now, when I’m pulling my hair out and wishing I’d never started the thing in the first place.