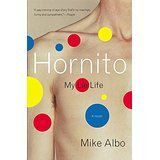

Mike Albo’s first book, Hornito: My Lie Life (2000), labeled a novel, switches between the viewpoint of a gay kid trying to stay alive physically, mentally, and spiritually in the American suburbs, and that of his adult self, hanging out in New York City’s queer scene in the 1990s. He tries to find love, or decide if he even wants love, while dealing with the world’s association of being gay with “dirtiness.” It feels both true and wildly imaginative, as if the “this is just a novel” shield protected Albo the writer so he could let Albo the character slide all the way off the rails. Some of his sentences, even at their funniest, gave me what Hornito’s main character would call “cry-mouth,” like this passage:

When I was a kid, I looked deep into the cruddy, misshapen plastic faces of my soldiers and Galactic Man toys. They would hold their weapons and helmets and ray guns with their fixed wartime expressions, but I would look for the hint of feeling in them. I would stare at them and wait for their faces to crack and for them to sigh and say something like “I’m really really homesick” so that my life would have an emotional crescendo.

Albo is a master at turning nostalgia against itself: Just as I was losing myself in the sights, sounds, and smells of the ’70s—recalling playing with those toys or listening to that music—the scene or tone would change. Toward the end, as the book cuts between Mike the teenager’s diary and Mike the grown man’s ultra-dreamy thoughts about an unattainable lover, the tension mounts and the writing becomes almost musical, overlapping so beautifully that you stop wanting to separate what is happening to Mike at fifteen from what’s happening to Mike at twenty-seven. It’s as if two instruments are playing the same song, only one is slightly out of time. Albo seems more at home in New York’s tradition of downtown performance than in any literary canon, but his own work has influenced some of the boldest young writers around, not least Brontez Purnell, author of the memoir Johnny Would You Love Me If . . . (My Dick Were Bigger), who read and spoke with Albo earlier this year at the Bureau of General Services—Queer Division, an LBGT bookstore and event space in Manhattan. (The discussion was moderated by Ted Kerr and William Johnson.)

Brontez Purnell: I tried to interview you for the first issue of my zine Fag School, in 2003 or 2004, but I lost my Hotmail account.

Mike Albo: Those were the creepy early days of the Internet! Hornito was such a strange book: It wasn’t a bestseller or anything, but there was something about it. . . . I’m so grateful for the people it brings to me.

Purnell: I was young and didn’t quite have access to that life until I moved to San Francisco and was like, “Oh, I can go out and have sex, I can be funny, I can be vulnerable.” Paired with the feminist background I had, and, like, confessional storytelling, Hornito was really a touchstone.

Moderator: Your first novel and Johnny Would You Love Me are both fiction, correct? The press release says they’re fiction, but they blur the line between fiction and memoir. Was there hesitation about going full memoir?

Purnell: I went back home to Alabama and I was at Barnes & Noble and I went to the memoir section and I just got so fucking grossed out. I was just like, “No.” You know what I mean? Yes, obviously it’s based on a lot of real things in my life, but I’m an actor, so the book is sometimes what I wish I did and what I wish I didn’t do. And there’s another thing, too. This girl who’s a big journalist and I had this conversation about how, with women writers and gay-male marginalized writers, they always want us to spill our guts so they have dirt on us, to throw it back in our faces. A friend of hers was trying to write a cookbook, and the publisher said, “Well, you should find a way to mix your sex life in with the cookbook.” He was like, “Do you have any problems with your father?” And then she was like, “I’m trying to write a cookbook, why are you asking me to spill my guts?” So, I mostly say that it’s a fake memoir.

Albo: I think all memoirs are lies, because everything you write is fiction. Technically, you can’t write something like, “Um, that’s Paul, not the Paul I mentioned before, but the other Paul.” So you have to create fake names. You have to zip up scenes. It becomes fiction by just putting it down on paper.

Moderator: Mike, you’ve mentioned that Spermhood is like a sequel to Hornito?

Albo: Yeah. Purely because they’re both based on diary entries. Hornito came from when I was in grad school for poetry. I was at Columbia. The only classes I think I tuned in to besides poetry were nonfiction. I started writing all these essays. It was also based on my diary from 1997, and this guy that I was just over the moon about. Hornito was this blob of diary entries and truth that I fictionalized. Spermhood is also based on a diary, from 2012. It was about all the times when I went to these clinics to jerk off into a cup to have a child, and how weird that is, and all the weird straight porn you have to watch at these sperm clinics, and how casually homophobic the reproductive industry is. Suzanne, my friend, was the birth mother. And gay-male sperm is quarantined if you’re an anonymous donor. We didn’t know where that fit in with us doing it in a clinic, so Suzanne and I had to portray ourselves as a sexual couple—I felt like I was in East Berlin. They were both emotional stories, and I haven’t done that in a while, so it seemed like Hornito 2.0.

Moderator: You deal with depression, isolation, with drug use, both awesome and non-awesome, and you’re also talking, in both books, about what it is to get older and stay queer or stay, like, outsider. What is that experience for you and why is it important to put it down on the page?

Albo: It’s so weird that queer has become a term that I gravitate toward now, because I didn’t know that being gay was going to be so boring. I was so nervous about being a father figure of some kind, I was like, “I’m not gonna be there all the time, like, I don’t know who I am for this child.” Suzanne, who’s “Caroline” in the book, said, “I want a queer family. I didn’t want a traditional family.” That was really liberating to me. Post-child I feel like the same person and the same weirdo. It’s not like in those movies when someone has a child and then their life changes and they, you know, sell their car and center themselves. I’m so un-centered, I’m the same weirdo that I’ve always been, so I guess I’m queer.

Purnell: Here’s the thing about the word queer, OK? I’ve been trapped in San Francisco for too long, and the word queer—it’s like everyone’s queer now. I’ll be sitting there talking to a guy who vaguely thought about sucking a dick in college, sort of. And he’s like, “Our struggle is queer freedom.” I like to refer to myself as an old-school homosexual, not a queer. But that’s just me. I came in through this ’90s thing that doesn’t happen anymore. You had to stay up to watch the independent-film channel to see Beautiful Thing at 12 am. Or you had to mail off to Kill Rock Stars and you had to really fight for that—wait three weeks for records or old-school homocore zines. Information filtered in so differently. I feel, with the Internet and how awesome and democratic everything has become, it’s also just shut a lot of shit down. People who would have written a personal zine now just post on their Facebook page or whatever. I get older, and I definitely feel alienated. I was watching a movie last night, In Search of Margo-Go, and there was a line in it: “Stuck in the groove of a record that’s out of print.” I feel that way, but I also love the groove of that record. It’s great.

Moderator: But the groove you guys are both in is actually like a really soft groove. Right? There’s a line in Hornito where you’re like, “I always struggle for the soft stuff.” There’s a line like that toward the end. And then, one of the best lines in your book is when you say, “If there’s a hell, gay boys are going to go there for how we treat each other.”

Albo: Reading Johnny, I was struck by the dance scenes. You’re at your dance class and there’s a spiritual element to it. It’s a gross word to use, but there’s a spirituality that you’re addressing that I hope I am addressing, too. I’m not sure it’s very popular in popular-gay-marketable culture. Whatever that means. We’re not allowed to be thinking too much.

Moderator: Or feeling too much.

Albo: Yeah, or showing our shitty thoughts. As successful or liberating as gay culture has become, we’re still not able to be sexual in this really weird way. And, when you bring it up, it’s like, stop complaining.

Purnell: I fucking hate that. First of all, I’ll bitch any goddamn time I feel like, when I feel like it. It goes back to masculinity. Your soccer dad saying, “Hey, toughen up kid, you know it’s all in your mind. It’s you and not the world that’s crazy.” I learned a long time ago that I am fucking nuts, but the world is nuts also.

Moderator: Both books talk about HIV and how it was experienced in different times. But there’s a through-line from the late ’90s to 2015. You both pick up on similarities, and, obviously, differences. And I wonder if there’s been excitement around that for both of you, or pushback?

Purnell: I was completely afraid. I’m in that weird snapshot generation—none of my friends were dying, but we were pre-PrEP. In my twenties, living in San Francisco, I was at bars with boys from Treasure Island Media [a gay pornography studio]. I was having sex with some of the Treasure Island Media boys. And there was still a slut-shaming division. In the San Francisco hub, there were definitely the boys who had their monogamous boyfriends. Then there were the boys who didn’t quite fit in, and if you’re a boy who doesn’t quite fit in, you’re going to try more extreme sexual shit. We were the boys getting drunk and getting fucked at the park. Going to the bathhouse on drugs. It was important for us to write about our experience.

Albo: There’s nothing like putting your sperm in a lesbian to make you think about your sexual activity. I would be like, “I know I’m negative, I know I’m negative.” In Spermhood, I write about my first date. I was in college. I went out with this guy who had watched his lover die. He thought HIV could be contracted through saliva, so we rubbed cheeks. On his bed. With the sperm donation, all that stuff came up again. I was just so scared all the time that I was infecting these women. No matter how many tests I took.

Purnell: Growing up, I’d meet men in their ’40s, who I would date, who said they thought my sex life was so crazy. “When I was your age, I didn’t do any of the shit you do. I would have never thought of it.” One guy explained it really well to me. He said, “HIV just kinda happened upon us. I feel sorry for your generation because when you have bareback sex, you’re making a moral choice.”

Moderator: As someone who does AIDS work, I’d be reading your book and thinking “don’t say that out loud!” But it’s important that we say those things out loud, because fiction is how we change hearts and minds, right? You can only read so many Huffington Post essays. On the page, Brontez, you’re sometimes fiction, sometimes not, right?

Purnell: I’ll never tell.

Kathleen Hanna is the lead singer of The Julie Ruin. The Punk Singer, a documentary about her, was released in 2013. Her review of Purnell’s Johnny Would you Love Me If . . . appeared in the Apr/May 2016 issue of Bookforum.