Nell Zink lives in Brandenburg, Germany, but writes mostly about Americans and their countercultures and excesses. Her novels tend to be funny, immensely contemporary, and a little chaotic—in their careening prose style as well as in their joyfully unwieldy premises. She’s written about a group of anarchist squatters navigating real estate and movement strategy in Jersey City (Nicotine); a white lesbian who, having gone on the lam, successfully passes as Black in the woods of Tidewater, Virginia, where Zink grew up (Mislaid); and, most recently, a Lower East Side post-punk couple whose daughter stumps for Jill Stein (Doxology).

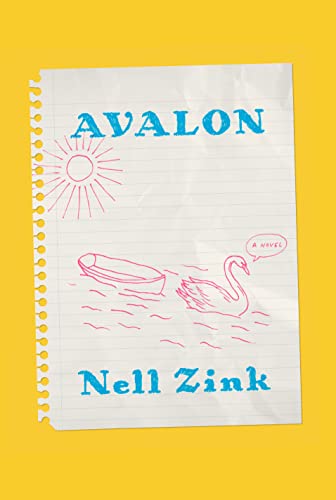

Her latest novel, Avalon, is narrated by Bran: a Zoomer orphan who’s spent her Cinderella-ish childhood living in the custody of a threatening and reactionary common-law family, the proprietors of a Southern California topiary nursery. After her high school friends go off to college and leave Bran laboring in the dust, she meets Peter, an East Coast aesthete and the sort of person for whom “getting a degree was basic hygiene, like washing behind your ears.” Like Zink herself, Peter has seemingly read everything, and his appearance in Bran’s life activates her desire to become a self-taught antifascist screenwriter, and also to get a boyfriend. As she slowly liberates herself from life on the farm, she and Peter follow each other around California, talking about utopia and flirting.

When Zink and I spoke last week, she had recently returned from a rafting trip on the Oder River.

How was rafting?

So many things went wrong in interesting ways, yet we managed not to lose our lives. We ended up like in that classic cartoon scene where you’re drifting down a river, and suddenly you find the water is moving faster and faster and you hear that rushing sound of a waterfall. There were all these moments of disastrousness but with happy endings.

That sounds like a lot of your fiction. In Avalon, there’s danger in the background, and your characters spend a lot of time trying to produce utopian cinema against the grain of a culture that they think encourages violently fascist artistic tendencies.

Which they see everywhere, because they are everywhere. It’s become impossible to get people’s attention with work that’s not somehow violent and exploitative and dystopian.

Do you think that’s true of literary fiction?

I’d say, yeah. It’s not like I read everything, but the way you get people’s attention is always by, you know, violating the cosmic order. Great stylists do it with every single sentence, or once a paragraph—they’ll do something terribly wrong. The use of words is unexpected and that’s why people admire them: because there’s this constant feeling of alienation, of getting a jolt. Harmonious stuff that goes down too easy isn’t admired as art.

But increasingly, I’ll read reviews that make a book sound completely harmless, like nothing terrible happens in terms of content, and then when I read the book it turns out that alarmingly bad things happen starting on page one! I don’t know whether people are desensitized because they’re used to reading such horrifying stuff or watching horrifying TV. I’m thin-skinned about violence, so in my own work I try to keep the stakes high without actually having the content go too far. There’s some pretty hardcore stuff implied in my books, but I try not to make it exploitative, where I’m just trotting out the acts of violence to keep people turning the page. Which I think is, unfortunately, a lot of what it goes on in some very acclaimed literary fiction.

Avalon is set in LA, and so many of the concerns of the novel—surface and superficiality, the film industry, Adorno—cohere around its setting. With the exception of The Wallcreeper, all your books have a similar relationship to other US cities. Why do you keep writing about America?

I have a lot of American material stored up and I guess I’m working my way through it. My uncle, who died very recently and whom I visited frequently, moved to West LA in 1955, and my grandma lived in Santa Monica, plus I was born near there, so I have a relationship with that town that seemed to me like something I could use.

I live in Germany now, but I’m not part of any expat community here—for twenty years, all my friends were German, before I met the writer Rebecca Rukeyser last summer. It would seem weird to write about Germans and have them speak English. It crossed my mind that my next novel could be about expats. There seems to be more interest in Europe than there used to be. What do you imagine when you think of a novel that takes place in Europe? The most conspicuous thing to me is the welfare state. Maybe because in my consumption habits I’m a bottom feeder, unless you count the organic food.

Bran, the narrator of Avalon, is truly pitiful and disenfranchised. But she’s also got a pluckiness and chutzpah that I’ve seen in a lot of your characters, many of whom are also young women fleeing from terrible men. What draws you to that profile, of punky women with bad boyfriends or bad stepdads?

Thirty years ago, when I was writing stories about animals, a lot of my heroines were, like, heroic baby lambs that would get very huffy when they realized something was going terribly wrong—there’s an injustice taking place!—and then they’d hammer on it with their little flinty hooves. Completely ineffectual, but righteous. I guess that must be an ideal of mine. For this book, I was thinking a lot about the literature of chivalry that I was raised on—books like The Little Duke by Charlotte Yonge. And the kind of poems I don’t think they make kids read anymore, things like “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” or books about Spartans. Even something like Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, where there’s this idea that if you learn to survive absolute privation, you gain a kind of strength that isn’t available to everyone. The novelist Atticus Lish gets at that idea too, but always through very hardcore situations, like the military or being a refugee or a terminal patient. But it seems to me that life in an unpleasant family or relationship can also instill those attitudes.

In all your novels, we see a scrappy DIY counterculture of some kind, whether it’s squatters or punks or lesbians. Usually there’s a lot of fondness for those subcultures, but in Avalon, the fringe-y characters are kind of threatening—there’s a biker gang that chases Bran around and terrorizes her.

You know, with that sort of character, you either make them violent and scary and proud of it, and then you’re just in cliché land—you might as well be watching TV—or you portray them really well, like, say, Tom Drury does. In his very first novel, The End of Vandalism, there’s a character who’s an arrogant small-town asshole, and he does such an incredible job of conveying how this character thinks he’s perfectly harmless and nice. It never crosses his mind that he’s a bad guy.

But I’m more interested in figuring out what I can give to readers that doesn’t fascinate them simply because it’s like watching a car crash. Of course, there’s irony in there, because I make Bran’s early life a total car crash, before she enters this strange relationship with Peter. There’s a threat that things are going haywire, but it’s not that you think this guy might want to hurt her. I try to bring in an element of unpredictability without making things too realistic. The arbitrariness of reality doesn’t work in fiction. People want foreshadowing and purpose. That’s why I put the end at the beginning. The first page of the novel gives away the conclusion.

There’s all this great material in the book about work. But then Bran—who’s narrating the book in the first person—skips over the details of a lot of her labor, as if she wants to spare the reader from hearing about her hours spent doing topiary grooming. Why not give us lengthier descriptions of her work?

I think Bran, as a narrator, wants to cut to the chase. It wouldn’t make sense if this character were to suddenly develop a Notebooks of Gerard Manley Hopkins–style interest in describing boxwood leaves. It just would not. I mean, a beautiful, luminous description of doing something tedious—I could write one of those, but it wouldn’t involve Bran. I myself have had transcendent experiences of mindfulness by doing some repetitive task. I vacuumed pools, I did masonry work where I was doing the same little gesture with a hammer eight hours a day every day. My attention span really expanded. When I sat down to read a difficult book, I could concentrate on it much longer after I had done that work. But that’s my story, not poor little Bran’s. She just wants to have an excuse to raise her head and look people in the eye.

I was intrigued by the very clear dichotomy between Bran, who’s essentially feral, and Peter, who wants to seem omniscient and well-read to the point of being a little bit annoying. It occurred to me that most characters in fiction probably fall somewhere between those two poles. I wondered what you thought you were able to achieve with such extreme characters.

It just interested me: the contrast between her being quick-witted but not well-read—she does know a little bit about Arthurian legend—and Peter’s erudition. And the question is: Why is that interesting to him? He can’t learn anything from her. Is it just the way she looks? And why is she interested in him? Is it just the way he looks? I wanted to keep that a little bit up in the air. Is what’s going on just teen horniness, or is there something he has access to that he understands that she needs?

What do you think?

I don’t know yet. I mean, I only wrote it like a year ago, and I tend not to feel like I get my own books until it’s been longer than that.

What were you reading while writing this book?

I was reading the kinds of essays, in German, that academics write about the kinds of things that Peter is obsessed with. But my big reading event of that period was the diaries of Victor Klemperer—one of the great reading experiences of my life. It’s like if Proust were not about venal parties. It’s nonfiction, and takes place from 1933 to 1945 in Germany, from the point of view of a middle-age Jewish intellectual who survived it all out in the open, because he had a so-called Aryan wife who stood by him. He lived without having to go to a camp. And it’s so incredibly moving, because it’s a diary, so as he’s writing it, he doesn’t know what’s going to happen. There are constant bits like, Hitler’s going to get voted out. He’s going to lose the war. Everybody secretly hates him, nobody takes this guy seriously. The Americans will be here next week. It’s the most magnificent book.

Because of that, I had it on the brain that it’s possible for a book to be truly good. And, not being Victor Klemperer, I thought—well, it’s not like he’s such a great writer, but he was unbelievably brave to do it at all, and his wife was unbelievably brave to smuggle his diary pages across town for safekeeping. Everybody was brave as shit to make this book exist. It makes you think writing books is not a complete waste of time, which is always a good starting point.

I definitely think Avalon is about bravery!

Maybe that was a reason to want to have a brave character, without her, you know, having to fight in a war.

You famously wrote your first few books really quickly. I thought of that process when Bran says that to write a screenplay, “All I had to do was open my mind and channel the culture.”

Channeling the culture is easy, but it’s not what I do. I get quoted as saying I write fast, because I didn’t always know what writers mean when they talk about their process. In my mind, I do a draft, and then I revise it. Whereas other people—I think they write the exact same way, but they talk about it differently. They spend years planning, and then they go to some writers’ colony for three weeks and hammer it out. But they’re smart enough to know that for PR purposes, they started writing this novel the day the last one came out. I got a real object lesson in this from a writer I met recently at a dinner party. She started talking about her process, and she said it involves a lot of knitting. She was like, “My new book took me ten years to write. I must have knit a hundred sweaters!” I thought, this is the exact attitude your accountant always wants you to develop. They want you to think of everything as work-related.

So you can write off all that yarn.

Other than collecting receipts for your taxes, I do not see the point of thinking like that, except that it saves you from being quoted in the New Yorker saying you wrote a novel in three weeks, like I was. I mean, I drafted the first part of The Wallcreeper in four days, and for that I’m a legend even to myself. But doing the rest of it took me almost a year.

How did this one go, comparatively? It’s very breezy to read, but it’s also a classic novel of ideas. Did it involve more research?

Compared to Doxology, it was a cakewalk, because I knew exactly what I wanted to do. In terms of research, the issues that come up in the book have been building up in my mind for like twenty years. I could make a case for saying it took me twenty years to write this book.

But I want to say something else about “channeling the culture”: that it’s the easiest thing in the world to do. To just open your mouth and talk the way other people are talking—if you do it with a certain level of articulation and brilliance, it can be a whole lot of fun to read. But that’s not, to me, what a writer should be doing if they want to look in the mirror and respect themselves. I want to be constantly undermining my own stream of consciousness, teasing out what’s wrong with it myself. I know that to a lot of readers that makes my writing fascinating in a way other people’s writing isn’t necessarily, and that’s why I have no desire to stop doing it, even if it’s not really a recipe for commercial success.

Lisa Borst works at n+1.