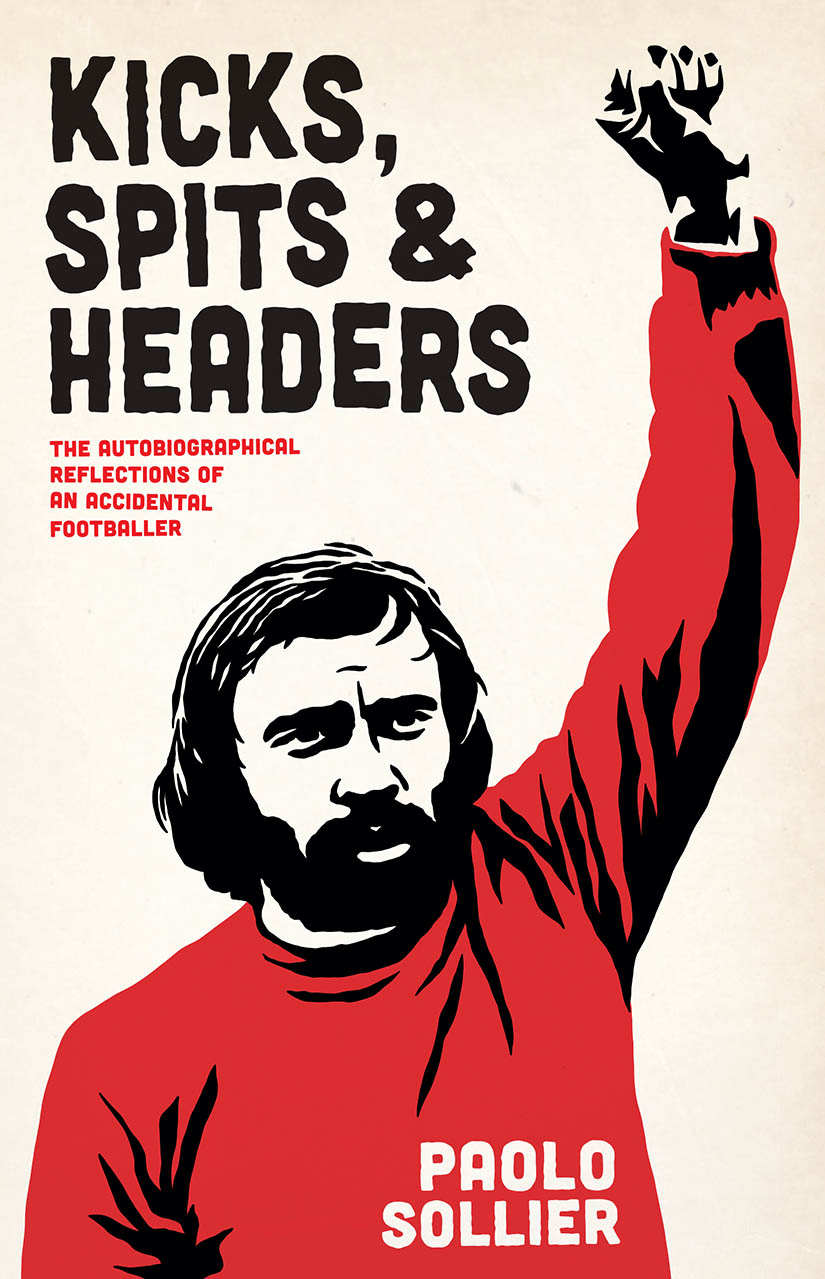

In the 1920s, an anarcho-syndicalist union in Germany distributed a pamphlet beginning: “May God punish England! Not for nationalistic reasons, but because the English people invented football! Football is a counterrevolutionary phenomenon.” Fifty-five years later, in his recently translated memoir Kicks, Spits & Headers: The Autobiographical Reflections of an Accidental Footballer (1976), Torinese leftist radical and professional footballer Paolo Sollier claps back: “I think that sports are an important field to be active in. One which the left has always avoided because of a question of priorities, but also because of its own inability.” Sollier’s discussions of popular football culture emphasize that the sport has the potential to retain its radical roots despite its standardization and cooptation by elites.

Written in full-frontal, beatnik-worthy streams—jumping quickly from a defense of left-wing political violence to regret about sleeping with a fascist woman back to reports about comrades framed by the Italian state—he proposes that football can be a terrain for building proletarian consciousness. Or as anarchist writer and footballer Gabriel Kuhn puts it in his definitive radical history of the sport, Soccer vs. the State: “The instrumentalization of football has little to do with the game itself. The powerful instrumentalize everything, including sports, arts, and consumer culture.” While some Marxists might still claim that organized sports are an “opiate of the masses,” Kuhn counters that “the solution is not to fight football but to fight a power structure that relies on mass control and distraction.”

Rather than faulting the game for the political alienation of workers, Sollier points at Janus-faced Marxist organizations. Critiquing the Italian Communist Party (PCI), for example, he asks cheekily, “Is the Party the opium of the people?” In the late ’60s and early ’70s, autonomist Marxism and workerism developed critiques of the state-form, trade unions, and mass political parties. Abandoning the fixation on a vanguard, those militants and theorists instead saw working-class power in wildcat actions and the refusal of work, worker’s inquiries, student movements, and alternative forms of life. Sollier brought this perspective to the pitch. An active member of the ultra-left political party Avanguardia Operaia (Workers Vanguard), for every goal he scored for Perugia, his contract stipulated the club take out two subscriptions to the party’s newspaper.

At times, Kicks, Spits & Headers reads like an Nanni Balestrini novel, in the form of an unedited diary. As in the latter author’s account of the 1960s workers’ revolts We Want Everything, Sollier’s direct first person has the effect of making the tension of those years feel more present. Between gripping accounts of major football matches that led his lower-league team to second place in the top flight, Sollier recounts Molotovs thrown into the offices of a neo-fascist organization, the 1969 Piazza Fontana terrorist attack, and the general pressure during the “years of lead,” when state repression and revolutionary violence were ubiquitous. All of this is braided with raunchy Bukowski-style sexcapades and decorated with handsome language: “eyes fixed like boiled eggs” or “I certainly feel more homosexual than I do prettyboyimperialist.”

During the postwar years, liberal and Communist party leadership helped build the First Republic through heavy industrialization, extractivism, and mass-consumer culture, founding a deeply corrupt system including many politicians and functionaries whose past alignments with Fascism were ignored. Simultaneously, as elsewhere in Europe and South America at the time, unprecedented amounts of money poured into football, and ticket prices skyrocketed, keeping many workers out of stadiums. This explains why Sollier’s scorn is most often reserved for consumerism and the cult of celebrity. “This issue of signing autographs is really a dangerous mania,” he writes of his refusal to sign autographs. “These hurried scribbles are an example of one of the rules of this system: to give value to things that don’t have any.” Not even children should get autographs from famous footballers, he exclaims: “No for god’s sake, educate them from the start.” Instead, he used interactions with fans as a tool of political outreach. When a “comrade” from Avanguardia Operaia asked for his signature, “I told him to go fuck himself. . . . I told him that being revolutionaries means being different, means changing things, from the big things to the little crap like this.” As Sandro Mezzadra describes in the book’s preface: in the 1970s, for many people the stadium became a training ground “in Italy, not merely in the sense that they became familiar with techniques to confront the police, but also because they had a chance to experiment with practices of community building among friends that in a way resonated with the ones promoted by the revolutionary movement.”

In recent years more attention has been given to how corporate and political powers use organized sports for their ends, and how corporate forces can be contested on the same stage—what sportswriter Dave Zirin terms the “Kaepernick Effect.” Predictably, sporting leagues have been quick to recuperate anti-racist and social-justice issues. Beginning in June 2020, following the George Floyd rebellions, footballers and referees in the Premier League (England) have been taking the knee before each match. Watching a Crystal Palace game recently, I noticed Wilfried Zaha of the Ivory Coast standing at attention; he later commented that racism from fans continued notwithstanding the now-emptied gesture, so why play a part in the charade. In one of the most striking moments in Sollier’s book, while playing against Lazio, an Italian team with a strong fascist fan base (to this day), he finds himself faced a mob of ultra-right-wingers flying the fascist salute and shouting “Sollier asshole.” He chooses not to respond, knowing that his signature raised fist would be used by the media to further their “both sides” narrative about leftist youth vs. fascist thugs.

After the Russian state invaded Ukraine, there was no shortage of reactions by football organizing bodies. Russia was kicked out of World Cup qualifiers, their teams banned from European club competitions; a great number of articles were written about the sanctions on Chelsea-owner Roman Abramovich. Many pointed to glaring contradictions: Why didn’t this happen when Russia invaded Chechnya or annexed Crimea? Why wasn’t the US similarly punished after the invasion of Iraq? Why do Israeli clubs play in European leagues as they violently occupy Palestine? With these debates in mind, Sollier’s autobiographical screed looks incredibly prescient. He acknowledged the possibility of radical culture developing through football but also knew it didn’t stop at the edges of the pitch. “The accusation is that I opportunistically use sports to do politics. Except that I do politics completely independent of the fact that I’m a footballer.”

Andreas Petrossiants is a writer and editor living in New York. His work has appeared in Historical Materialism, Artforum.com, Bookforum.com, The Brooklyn Rail, Hyperallergic, Frieze, AJ+ Subtext, and e-flux journal, where he is the associate editor.