If jails and prisons are to be abolished, then what will replace them? This is the puzzling question that often interrupts further consideration of the prospects for abolition. Why should it be so difficult to imagine alternatives to our current system of incarceration? There are a number of reasons why we tend to balk at the idea that it may be possible to eventually create an entirely different—and perhaps more egalitarian—system of justice. First of all, we think of the current system, with its exaggerated dependence on imprisonment, as an unconditional standard and thus have great difficulty envisioning any other

- excerpt • June 23, 2020

- excerpt • June 18, 2020

In 2005, three police officers in Florida forcibly arrested a five-year-old African American girl for misbehaving in school. It was captured on video. The singer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte, like most others, was appalled by what he saw and initiated a campaign to train the next generation of civil rights activists: the Gathering for Justice, which in turn created the Justice League, an important force in the Black Lives Matter movement. At the core of the group’s demands is a call to end the criminalization of young people in schools.

- print • Summer 2020

In the twelfth century, the city of Cahokia, settled on mounds near the Mississippi River, had a population greater than London’s. Its trade and travel routes stretched to present-day Minnesota and Louisiana. Around 1350, Cahokia’s residents abandoned the city for unknown reasons, but its traces remained. In 1764, traders led by Auguste Chouteau built a fort across the river and saw the abandoned mounds. Assuming they were the remains of a long-gone civilization, the French traders thought the people living around them—a different group of indigenous people than Cahokia’s inhabitants—were colonizers. Chouteau’s men believed they had as much right to

- print • Summer 2020

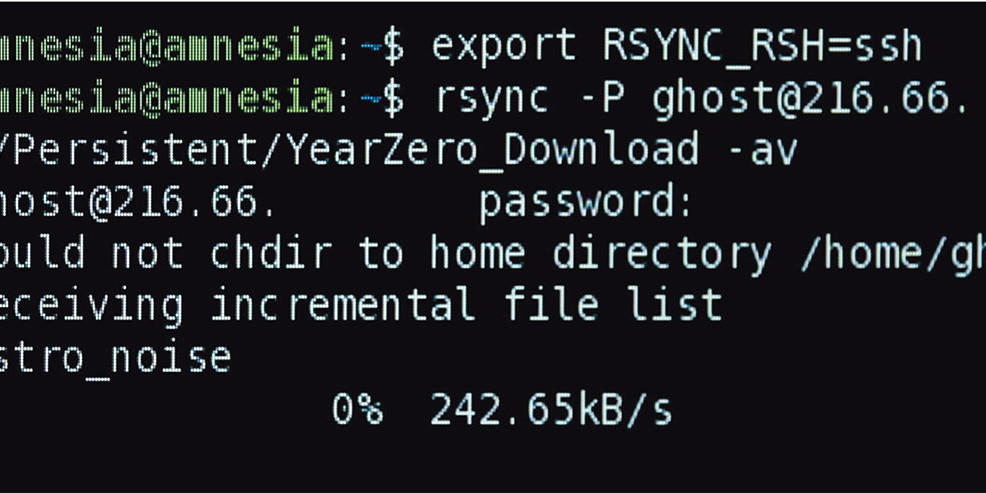

The mood, when a story about Edward Snowden begins any time before the news-breaking Guardian piece of June 5, 2013, is a clean dramatic irony. We know the identity of the anonymous source; the characters don’t. The greatest secret-exposer of his generation was himself an unexposed secret that winter and spring, a cipher who insinuated his way into journalists’ lives through encrypted channels, making vague and terrifying claims that were hard to grasp and verify. He could be a liar or a catfisher. It could be a sting; you’d spend the rest of your life in jail.

- print • Summer 2020

When Karla Cornejo Villavicencio was fifteen and growing up in New York, she called the restaurant where her father worked as a deliveryman and pretended to be a beat reporter at a city paper to get an abusive manager fired. In 2010, after she wrote an anonymous essay about being undocumented and a student at Harvard, she received her first offers to publish a memoir, which she rejected. But she is not, as she tells us in The Undocumented Americans, a journalist. “Journalists are not allowed to get involved” the way she gets involved, nor to “try to change the

- excerpt • May 7, 2020

Institutionalists have been warning about the breakdown of democratic guardrails for quite some time. An optimist might have fretted about these trends but noted that everything would be okay so long as the President acted like, you know, a grown-up—someone who recognized that with great power comes great responsibility. Unfortunately, Donald Trump really does think and act like a toddler. He has done so for most of his life.

- review • April 23, 2020

Even before the COVID-19 disaster, the American healthcare crisis felt so patently absurd, so coeval with a very 2016 flavor of political cynicism, that many Americans might be surprised to recall just how old the debate over reform really is. The first call for universal coverage arrived during the 1912 election, when rogue Progressive Party candidate Teddy Roosevelt campaigned on a national system modeled off those already available in Europe.

- excerpt • April 21, 2020

One of the key lessons of the history of fascism is that racist lies led to extreme political violence. Today lies are back in power. This is now more than ever a key lesson of the history of fascism. If we want to understand our troublesome present, we need to pay attention to the history of fascist ideologues and to how and why their rhetoric led to the Holocaust, war, and destruction. We need history to remind us how so much violence and racism happened in such a short period. How did the Nazis and other fascists come to power

- excerpt • March 30, 2020

Photo: Lord Jim/Flickr. a little knowledge can go a long way a lot of professionals are crackpots a man can’t know what it is to be a mother a name means a lot just by itself a positive attitude makes all the difference in the world a relaxed man is not necessarily a better man […]

- print • Apr/May 2020

For a long time, the internet seemed to resist description. Like the unconscious, the early Web was baffling, unsettling, even a little embarrassing. New users, unaccustomed to virtual terrain, compared it to a dream. Its inventors favored unhelpful hyperbole: Theirs, they claimed, was the greatest invention since penicillin or the printing press. Novelists steered clear of online life altogether, brandishing their abstinence as a sign of literary integrity.

- print • Apr/May 2020

Vladimir Putin’s Russia lends itself to being seen in Manichaean terms. Commentators at home and abroad like to picture a desperate struggle between the centralized state and a righteous but comparatively powerless coalition of prodemocratic forces. This black-and-white view goes back at least to the Soviet era, when small groups of dissidents who celebrated “living in truth” and refused to surrender to the hated regime found an eager audience among Cold Warriors. Their enduring romantic vision has shaped much of the Western discourse about Russian politics, at the cost of much-needed nuance and sober assessment.

- print • Apr/May 2020

“There are no ‘good guns,’” Charlton Heston once told Meet the Press. “There are no ‘bad guns.’ Any gun in the hands of a bad man is a bad thing. Any gun in the hands of a decent person is no threat to anybody, except bad people.” The merits of Heston’s argument notwithstanding, the dramatic force of his delivery was undeniable, affirming the actor’s status as one of Hollywood’s iconic heroes. Who could speak with more authority of guys good and bad than the man American audiences had grown up seeing in cowboy buckskin, shining armor, military fatigues, and the

- review • March 13, 2020

According to the CDC, the United States performed eight COVID-19 tests on Tuesday. Zero by the CDC itself, which seemed to stop testing six days ago, eight by public health labs. [1] The CDC offered no data at all for Wednesday. U! S! A! We are, of course, the greatest country on earth, so I’m betting we can do even better today: 8 + 2 = a perfect ten! No, wait—aim higher, America! 8 + 3. This nation goes up to eleven.

- excerpt • March 3, 2020

In a campaign that included many startling pronouncements, Trump’s pledge to build the wall in June 2015 became the iconic phrase that stitched together a right-wing nationalist tapestry of resentment, nihilism, and violent nostalgia. Mexico would pay for it. A form of imperial tribute recast as reparations to a wronged and aggrieved America, whose sovereignty had been violated by unchecked “illegal immigration,” unfair trade deals, and unfavorable inter-state alliances. Justice would finally be secured by a president with the boldness to reassert the rightful order among nations. The American people would remain composed of the white citizenry the founders envisioned.

- excerpt • February 25, 2020

The neighbors thought my mother was crazy. How to explain that she sometimes put her washing on the line, sometimes in the field, sometimes on the grass, and sometimes even hung it from the branches of trees? What sense did it make that she would often lay it in the shade or in the windiest spot weighted down by large stones like the punctuation marks of some secret message?

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Whether or not he was born that way, Ross Douthat is a defeated man. The child of hippie aspiring writers—a father who became an attorney and a mother who became a homemaker (both became published writers late in life: the father a poet, the mother a contributor to the Christian journal First Things)—Douthat arrived at Harvard in 1998 yearning to live the life of the mind and found himself among a horde of grade-grubbing careerists, most of them from affluent families, biding their time until they filled their reserved slots among the neoliberal power elite. This state of affairs became

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

When Hosea Hudson, a labor organizer and member of the Communist Party (CP) in Birmingham, Alabama, approached potential recruits, he didn’t minimize the stakes of what he was asking them to do: “You couldn’t pitty-pat with people. We had [to] tell people—when you join, it’s just like the army, but it’s not the army of the bosses, it’s the army of the working class.” For a black worker in the Deep South of the 1930s, there was no way to justify lying to fellow workers about what they were signing up for. Assassinations of labor organizers, often simply recorded as

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

As we enter what feels like the second or third decade of the 2020 presidential campaign, a question hovers menacingly over American politics: Can liberals get a grip? Three years into the Trump era, it cannot have escaped anyone that the country’s political system is in the throes of a major crisis. Yet the mainstream of the Democratic Party remains bogged down, lurching back and forth between melancholy and hysteria. “The Republic is in danger!” the Rachel Maddows of the world intone, but aside from a Trump impeachment that has no hope of actually removing him from office, the solutions

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Journalists often describe Chelsea Manning as a “whistle-blower.” This is understandable—I’ve called her that myself. The act for which Manning is best known, for which she has been celebrated and persecuted, is usually understood as a bold instance of whistle-blowing. But this is not how Manning primarily describes herself. On her Twitter profile, she identifies as a “Network Security Expert. Fmr. Intel Analyst. Trans Woman” and, first on the list, “Grand Jury Resister.” Grand jury resistance is the reason for Manning’s present incarceration. Last March, she was taken into federal custody for refusing to testify as a witness in grand

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

In the downstairs bar of a Brighton comedy club, I sat with sixty or so activists clustered around tables to discuss the four-day workweek. They were participating in The World Transformed, a radical gathering held alongside the Labour Party’s annual conference, where the party’s left wing hashes out proposals that it hopes Labour will adopt. Indeed, by the time this panel met, a shorter workweek had already been announced by Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell in his floor speech. The people in that club, then, were thinking about implementation, as well as dreaming about what they’d do with more free time.