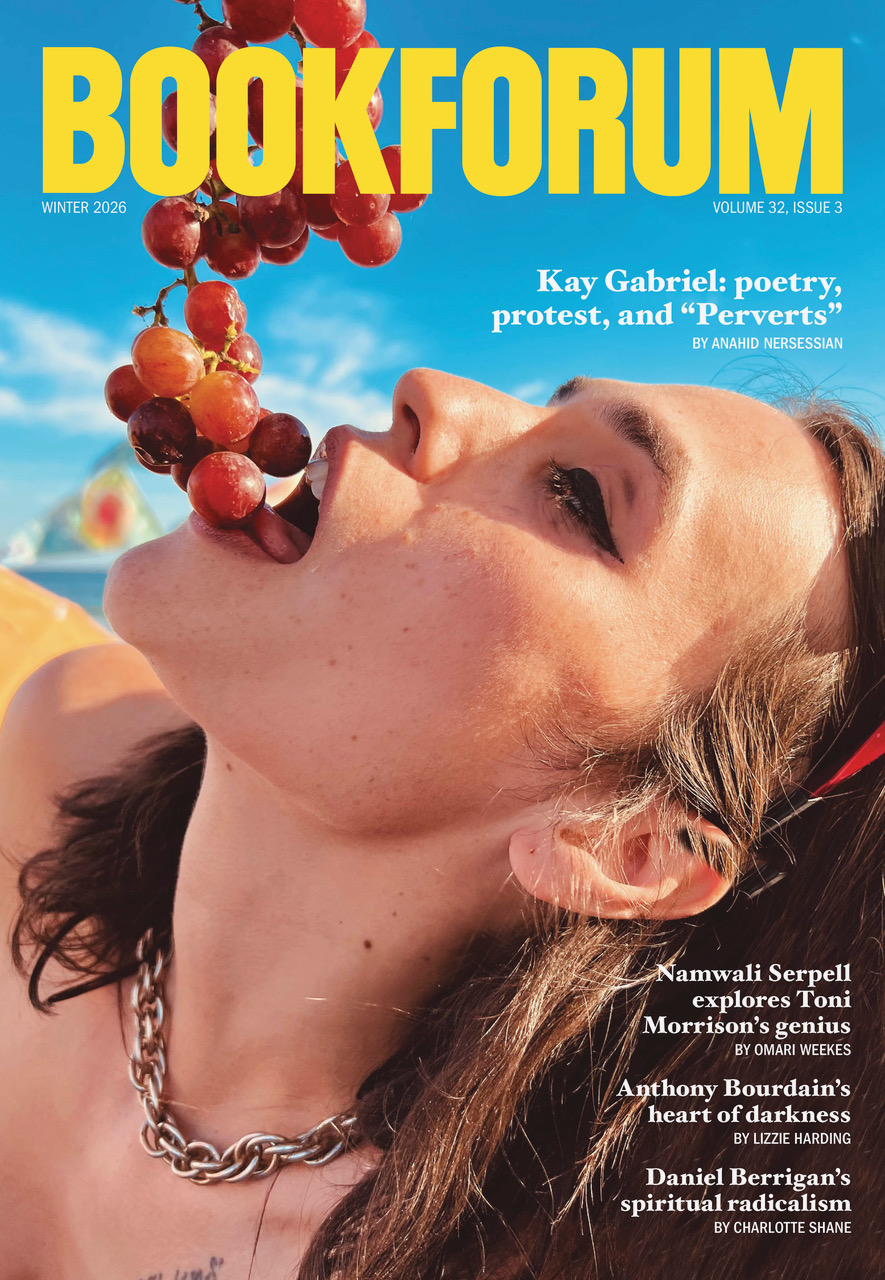

We’re happy to announce that the Winter 2026 issue is online now! This edition includes essays and reviews on Kay Gabriel and the “Nightboat School of Poets,” a collection of Anthony Boourdain’s writing that reveals new facets of the late chef’s personality, the enduring power of Catch-22, and much more. Plus: Omari Weekes on Namwali Serpell’s study of Toni Morrison, Mary Turfah on Wasim Said’s Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza, Andrew Chan on Taylor Swift, a conversation between Christian Lorentzen and A. S. Hamrah, and more. Subscribe or renew your subscription today to receive the print issue and support Bookforum. And consider making a donation or gifting a subscription. Thank you, as ever, for reading!