George Plimpton slept with Anne Roiphe and forgot about it. Doc Humes would show up on her doorstep late at night—then walked out of her life forever. Recalling her intimate encounters with another literary Olympian, William Styron, Roiphe writes, “I try to say interesting things to him. His eyes are always far away as if he were staring at me across a muddy river where the mist never lifts.”

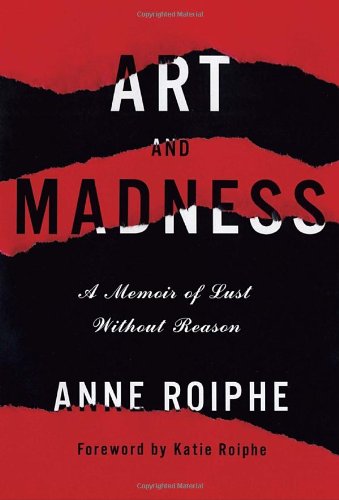

Call it the fog of gender war. Even if the introspective young narrator of Roiphe’s sex-trophy memoir, Art and Madness, can come across as a glutton for punishment, her experience of the hard-partying New York literary circle of the 1950s and ’60s might have been the best an intelligent and attractive young woman could have hoped for. “We girls, not yet called women, were like the Greek chorus,” Roiphe writes, “mopping up after the battle was over, emptying ashtrays, carrying the glasses to the sink.” She contemplates this tumultuous decade or so of her life with the cool remove of someone who has had a half century to think it over, during which time she has become an accomplished writer. She put herself through more emotional suffering than it was worth, she decides. But even if she paints an unsentimental portrait of the celebrated Paris Review set, it’s easy to understand why she remained a part of it.

Admittedly, readers of the author’s childhood memoir, 1185 Park Avenue (1999), will understand her reasons even better. That book picked through Roiphe’s upbringing, a privileged one soured by the stigma of Jewishness and by her supremely dysfunctional parents. In Art and Madness, we see Roiphe as a young adult yearning to break free in an era “when the lid was on.” Like her bohemian peers, she longs for a life that is “like the big waves at the shore, to be rushed into, to be ridden up and down, life that tasted of salt and could pull you out over your head.”

For a young woman who grew up with servants cutting the crusts off her sandwiches, Roiphe does an admirable job replicating the adventures of Henry Miller, André Gide, and her other literary heroes. While her classmates at Smith college are knitting socks for their Harvard boyfriends, she’s staking out a lesbian bar in Greenwich Village and losing her virginity to an American writer in Paris. That relationship ends the moment she realizes he lacks talent. “Perhaps I was a gold digger and my gold was literary fame,” Roiphe muses, with typical candor. She sees more promise in the man who becomes her first husband, a striking playwright who speaks in long, eloquent sentences but pawns her heirlooms to pay his bar tab and picks up other women right in front of her. On their honeymoon, he disappears on a four-day bender.

But Roiphe ignores her own needs to care for him—and for their child—in the name of art, which she sees as the only viable escape from everyday lies and convention. Great creators, therefore, “have permission to do the unthinkable because they cannot be bound by our rules.” But when her husband’s play flops, she starts to see the injustice of their arrangement for what it is. The marriage ends, and Roiphe is twenty-seven and ostensibly without a cause. The most surprising moment in this thoughtful memoir, then, is not her lukewarm account of the legendary scuffle between Humes and Norman Mailer, but her revelation that “there had never been a moment in my conscious life when I was not planning on becoming a writer.” Turns out that Park Avenue girl with the nice legs had words in her head the whole time.