In January of 1965, FBI agents closing in on mobster Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno discovered that the hellion son of an FBI informant code-named T-10 was raising hell alongside Bonanno’s own teenage son. Agents looked to exploit the two boys’ relationship to help break the case—until, that is, J. Edgar Hoover ordered his underlings to instead warn informant T-10 that his son’s mob associations might harm the confidential source’s fledgling political career. The Justice Department never did manage to pin a decent indictment on Joe Bananas. But T-10—and his fledgling political career—did just fine. He later became the fortieth president of the United States.

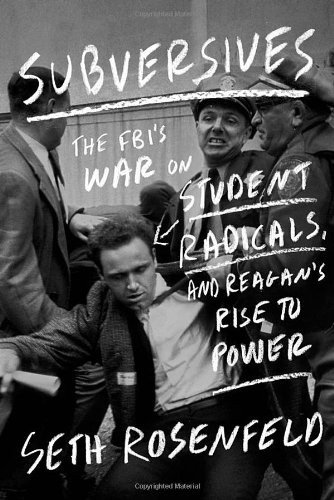

This is just one of at least a dozen revelations about one of the most studied men in history in Seth Rosenfeld’s new book. “Here was Ronald Reagan,” writes Rosenfeld, “avowed opponent of big government and people’s over-dependence on it . . . taking personal and political assistance from the FBI at taxpayer expense. . . . Moreover, he seems to have been unaware, or unconcerned, that in doing so he was becoming beholden to the Boss,” who now possessed the sort of blackmail-worthy secret anyone who has seen the recent film J. Edgar knows made even presidents slaves to the FBI. But such questions were moot when it came to Reagan: As readers of this unbelievably good book will learn, he was unblackmailable. There had never been any favor too big for Reagan to volunteer for Hoover, and no favor too small for Hoover to tender him in return—including, in March of 1960, sending out agents to track down a rumor that his daughter Maureen was living with a married man.

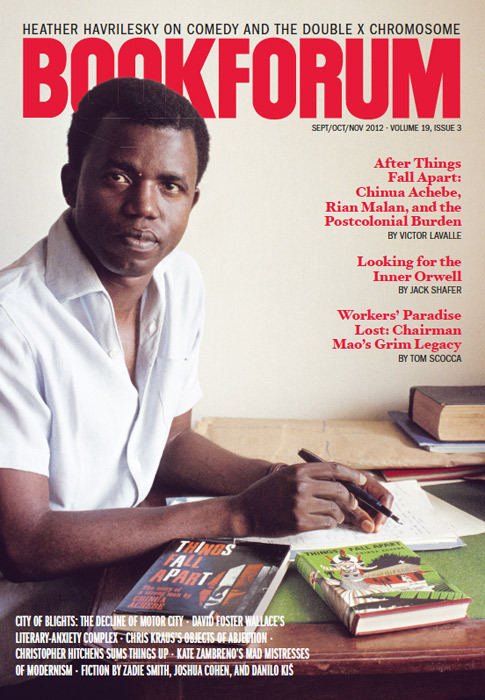

Rosenfeld reveals that Reagan’s relationship with the FBI, which began in 1947, when he became president of the Screen Actors Guild, was far deeper, and creepier, than anyone has ever known before. But documenting the depth of that covert alliance is only one of the amazing things this sweeping book accomplishes. The product of more than thirty years’ indomitable work acquiring the files via the Freedom of Information Act to yield these new secrets, this volume is also an outstanding primer on the postwar Red Scare; a riveting account of the origins, development, and philosophy of the New Left; and a penetrating look into the mind of Reagan. But most of all, it is the best account I’ve read of how the FBI corroded due process and democracy.

The core of the book pairs J. Edgar Hoover and Ronald Reagan’s twin obsessions with the University of California. The FBI founder’s paranoid fixation began in 1942, when he became convinced that UC Berkeley’s nuclear laboratories were nests of Soviet spies. One day in 1945, his agents scrawled down the license-plate number of a car in front of the home of a suspected nuclear-lab spy. The vehicle belonged to Clark Kerr, then an obscure labor-studies professor visiting a friend nearby. Kerr, a Quaker pacifist whose rare combination of uncompromising principle and institution-building skill makes him an unsung hero in Rosenfeld’s book, led a movement in the 1950s to fight compulsory loyalty oaths for faculty. The data already in his FBI files sealed the bureau’s conviction: He was working for the other side. So, Hoover decided more than a decade later, was Kerr’s greatest adversary, Mario Savio, a founder of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement in 1964, and with it, the New Left. Hoover was open-minded in targeting enemies, if not in anything else.

Hoover’s obsession with the university intensified in 1959, when a test for incoming freshmen included the question “What are the dangers to democracy of a national police organization, like the FBI, which operates secretly and is unresponsive to criticism?” What followed was one of those laugh-to-keep-from-crying moments that students of FBI history know too well: The bureau acted like a fascist organization by targeting anyone accusing it of acting like a fascist organization, all in order to publicly prove it was nothing like a fascist organization. Hoover’s right-hand man, Cartha “Deke” DeLoach, “swiftly mounted a covert public relations campaign intended to embarrass University of California officials and pressure them to retract the essay question.” The regents soon cravenly apologized, but the bureau still deployed thirty agents to discover who wrote the offending question. They settled on a UCLA English professor named Harry Jones, and they were probably responsible for the poison-pen letter later addressed to the UCLA chancellor reporting that the professor and his wife were “fanatical adherents to communism”—all a bit disconcerting to poor Professor Jones, who was actually a fanatical conservative, and (of course) hadn’t even written the question. That investigation also produced a sixty-page report on the University of California system that read, Rosenfeld writes, like “a description of a foreign enemy.” It portrayed the schools, which Clark Kerr had by then taken over and masterfully turned into the greatest university system in the world—neither Reagan nor Hoover cared a whit about that—as containing “a wide range of political beliefs,” but also fatefully harboring faculty members guilty of offenses such as getting Communist books in the mail, having “immediate relatives” who subscribed or contributed to publications deemed subversive, or urging the abolition of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The next year, police used high-powered fire hoses to wash students seeking admission to public HUAC hearings down San Francisco’s city-hall steps. The FBI report on the incident, “Communist Target—Youth,” said the whole thing had been orchestrated by Communists, and complained that Kerr refused to discipline a single student who was there.

Here Reagan enters the multilayered narrative. The former movie star, who helmed TV’s General Electric Theater, begged the bureau to let him turn “Communist Target—Youth” into a teleplay. Since the trial resulting from the FBI report had led to an embarrassing acquittal (the student who had supposedly started the riot by leaping a barricade and beating a policeman had been forty feet away when the incident occurred), Hoover shunted Reagan off. The one thing the FBI dreaded more than anything else was embarrassment, though it is typical of Reagan’s cast of mind that he would have been indifferent to such embarrassment. In Reaganland, there only were good guys and bad guys, and anyone who hunted Reds for a living was good. Which was why, long ago, T-10 had become one of the best informers the FBI ever had.

A month after his 1947 election as president of the Screen Actors Guild, he reported to two FBI agents that a couple of his political rivals within SAG “follow the Communist Party line.” He then tagged eight actors as outright Communists. Later, the SAG executive director, probably at Reagan’s direction, helped the FBI finger fifty-four more. Rosenfeld names them for the first time here. They included J. Edward Bromberg, a character actor who begged not to have to testify before HUAC because of a bad heart, was called anyway, was blacklisted, and died six months later of a heart attack. Reagan was still at it thirteen years later, reporting a kid who pestered him with questions “right down the Commie line” during a speech he gave at a “Democrats for Nixon” rally. The FBI duly opened a file on the kid under the heading “Security Matter—Communist.” (At that time, when an estimated 17 percent of American Communist Party “members” were actually FBI infiltrators, lefties joked that the party would collapse without the FBI dues.) This is the opposite of what Reagan always claimed: He said he never “pointed a finger at any individual.” It is also the opposite of the assertion of his most respected biographer, Lou Cannon, who wrote in 2003 that “I know of no one, either publicly or privately, whom Reagan called a Communist other than those who proclaimed their own Communism.” That sentence was once justifiable enough—precisely because Rosenfeld’s revelations are new. Cannon’s passage continues, however: “He realized that such accusations often damaged the accuser, and his sense of fairness led him in the direction of scrupulous political dialogue and away from personal vilification.” And that line is perfectly irresponsible. When it came to those he judged subversive, Reagan had no sense of fairness at all—like the time when a Black Panther was scheduled to address a course at Berkeley in 1968 and Reagan said, “If Eldridge Cleaver is allowed to teach our children, they may come home one night and slit our throats.”

That’s simply the public record. And now we have the private record. In 1966, Rosenfeld shows, Hoover secretly helped get Reagan elected governor, then in 1967 conspired with him to get Kerr fired. Around the same time, the FBI helped Reagan cover up lies on a report in which he omitted his past membership to organizations officially deemed subversive by the attorney general—and Reagan signed a form acknowledging that such false statements were punishable as a felony. (One of the great pleasures of the book is watching Rosenfeld, who has a true reporter’s nerves of steel, confront his subjects with these facts. Deke DeLoach denied the bureau would ever do such a thing; next, the Los Angeles special agent then in charge tells Rosenfeld it was standard procedure.)

As the political temperature in Berkeley intensified, Hoover’s vendetta against Savio took a harrowing turn. Savio was a reluctant revolutionary. He had more or less quit movement politics by 1966 and was utterly indifferent to the charms of Berkeley’s very few actual Communists (one of the only things I can fault Rosenfeld for is not noting that the FSM’s most memorable slogan, “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” referred to the annoying old Commies). Savio was also a veritable pacifist—one with profound psychological troubles. None of that made any difference to the FBI, which placed him on its Reserve Index—a list of over ten thousand people who were to be rounded up for incarceration in the event of a national emergency—because, an FBI document reveals, of his “contacts with known Communist Party members, his contemptuous attitude, and other miscellaneous activities.”

In 1972 this “contemptuous” man checked into the Neuropsychiatric Institute at UCLA to receive treatment after a bout with homelessness. “The FBI promptly updated its detention list to show the hospital as Savio’s residence, in case agents needed to arrest him as a security threat during a national emergency.” Rosenfeld calls his masterpiece of historical reconstruction and narrative propulsion Subversives. I don’t think he’s referring to the FBI’s targets.

Rick Perlstein is the author of Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (Scribner, 2008) and is at work on a book about the 1970s and the rise of Ronald Reagan.