Los Angeles is traditionally where factoids become fables and get passed off as philosophy. The true mystical secret of Zen ideas in particular is that they’re stupid. California is pretty stupid, too—which means that warmed-over takeout Zen has done a good business there. Consider, just for instance, the success of the Nichiren Shōshū sect: Its promoters have melded simplistic Zen ideas with materialism, and throughout the ’80s, suburban Angelenos gathered in living rooms, all chanting for happiness and/or a new car. It worked, too: Lots of them did eventually get new cars.

There is no LA without the transmutation of the great teachings of history into bumper stickers. And, at the top of that society’s circle of drivers, who, if not actors, will give us spiritual counsel?

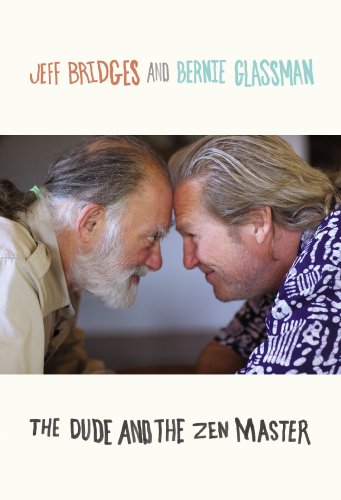

Jeff Bridges and Bernie Glassman, both Buddhists, are extremely good people, although only one of them has an Oscar. They have devoted substantial effort to ending hunger. Glassman has pioneered the idea of building functional businesses that employ the seemingly unemployable, starting with a bakery in Yonkers—the profits from which went to create housing.

They met, sure, in LA. “I met Bernie at a dinner thrown by a neighbor of mine for him and Ram Dass,” says Bridges, and then much later Bernie thought they should write a book about how Bridges’s character of the Dude, from The Big Lebowski, was a very Buddhist fellow, and Jeff Bridges was like, “OK, great,” and they “went up to my ranch in Montana” and “jammed for five days” while some guy named Alan took photographs of them and recorded their dialogue. Then Bernie’s wife dealt with the transcripts. (So it has ever been.)

The result is The Dude and the Zen Master (Blue Rider Press, $27), a book of “jamming” dialogue, a tremendously harmless, good-natured pile of mindlessness. The good news is that it’s innocuous, unlike works produced by many of the recent capitalist philosophers of Los Angeles, the Louise Hays and the Marianne Williamsons.

The less good news is that it doesn’t really go anywhere. The Big Lebowski is the only Coen brothers movie that I cannot watch and also the only Julianne Moore movie I cannot watch. Those are two of my favorite things—and yet, when this film starts, some sort of horror creeps over me and I have to stop. This book may explain why.

As an item of pop-culture consumption, The Dude and the Zen Master is mildly useful for the Jeff Bridges fan. He discusses working with Sidney Lumet (he wasn’t afraid of rehearsals!) and Francis Ford Coppola (he used improv!). His parents, Lloyd and Dorothy Bridges, were really quite amazing. Burgess Meredith introduced him to John Lilly, “perhaps most famous for his work with dolphins and interspecies communication, as well as experimenting with LSD.” He “got into drugs.” Hal Ashby infuriated producers because his scripts barely indicated the ideas he was seeking to develop into feature-length films.

What else? Bridges sleeps naked. He’s spent nearly as much time with his stand-in, Loyd Catlett, as he has with his wife—sixty films! He makes little sculptures of human heads and gives them to people. When he met his wife, she had a broken nose and two black eyes, and he was a “pouting asshole” for the first three years of their marriage.

Then, as you read along, the metaphors under discussion start to hollow out and magnify, as they would in a hallucination. The 1994 LA earthquake, and how it shattered expectations. How chicks and their mothers peck shells open from the inside and the outside at the same time, allegedly. (“If you’re attuned enough, you can hear the pecking of the universe saying, Peck peck peck peck peck, I want to be born!”) Hotei (also known as Budai), the deity with his bag of tools, is like Jonathan Winters wandering around a pharmacy. Solzhenitsyn. Wavy Gravy. Richard Feynman. Clowns. Santa Claus. Camus. Hitler. Lenny Bruce. 9/11. Primo Levi. The earth vibrates at 440 Hz. (It does no such thing.) The tallest tree gets the most wind.

Bernie does an annual retreat at Auschwitz-Birkenau. He also has pioneered a performative variation of the notion of a meditation retreat by taking to the streets without ID or money. “I always remember Robin Williams, back when he was Mork, saying that reality is a concept,” Bernie says. “Years ago I was watching TV and I heard these doctors talk about rebirthing,” Jeff says. So he sat down with his mother and she told him about his birth.

There are several pages—literally, many pages—that meditate on the song “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” as a teaching.

You have to befriend the self—that’s another teaching. “You’ve got to befriend the fact that Jeff can only do so much,” Bernie says to Jeff. “He does what he does,” Jeff says. “And because he’s famous, he’s overloaded by requests,” Bernie says.

At the end of the book, it’s like a long lost weekend in Los Angeles, and you really do feel like you’ve gone out of your mind. Maybe that’s a good thing—a Buddhist exercise in its own right?

“I remember meeting the artist Mayumi Oda at your Symposium for Western Socially Engaged Buddhism,” Jeff says at one point. “I looked at her gorgeous prints and asked her, ‘How do you do this?’ And her answer was, ‘It’s like I’m already dead.’” Yes! That is how I felt after finishing this book.