“This is not a novel,” says Poul Hannover, witness to this amazing story of the Holocaust. “No fancy trimmings.”

None are needed in Bo Lidegaard’s Countrymen. Lidegaard, the editor in chief of Danish newspaper Politiken, has pain-stakingly reconstructed an extraordinary story. And he tells it with the assurance of a journalist who knows he’s making literature.

Denmark had scarcely resisted the German invasion in April 1940, accepting Nazi occupation “under protest.” (The Germans preferred the term “under protection.”) For the next three years, the Danes were haunted by such questions as Why didn’t we put up a proper fight? and Was it right for politicians to have cooperated with the occupying power? As Lidegaard puts it, “There were no easy answers. . . . The war had amply demonstrated that even much larger countries could not stand against Germany.” So was it wrong for the Danes to have shunned the inevitably punishing outcome of armed resistance? Most Danes probably agreed with their prime minister, Thorvald Stauning, who recommended that they “play for time”—and “avoid . . . major disasters.”

As it turned out, the Danes seized the next opportunity to prove their courage. By the close of 1943, there were 150,000 German soldiers in Denmark, then a country of about 3.8 million people. But the war news by the summer of that year emboldened the Danes, and by August there were sporadic strikes and even sabotages of equipment and supplies intended for the Wehrmacht. Cooperation between the Danish and German governments came to an abrupt end, and martial law was imposed.

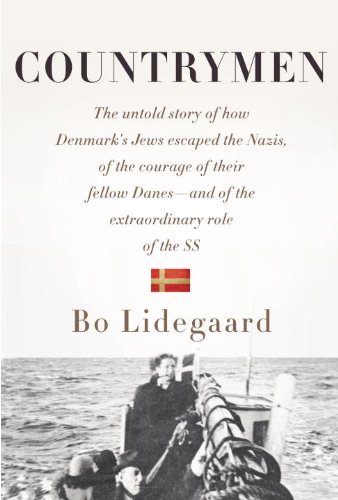

Everyone knew what would happen next: the roundup and deportation of the tiny country’s Jewish population. Over two incredible weeks—from September 26 to October 9—7,742 Danish Jews and 686 non-Jews who had married into Jewish families were evacuated from Denmark, most from Copenhagen harbors on cutters and other small boats, braving the choppy waters of the Baltic Sea for Sweden and safety.

The flight of the Danish Jews is spirit-stirring material that has somehow never been the subject of a book, though the basic facts have been known for decades. In a bizarre paradox, it was Adolf Eichmann who alerted much of the English-speaking world to the story, via an account reprinted in Life magazine in 1960: “Denmark created greater difficulties for us than any other nation. The king intervened for the Jews there and most of them escaped.”

Actually, King Christian X didn’t openly intervene—he mainly galvanized Danish resistance when he said that the right attitude for Danish citizens would be for “all of us to wear ‘the star of david.’” The king’s stance reflected a belief that most Danes already held. Since the early 1930s, the Social Democratic Party had succeeded in linking “the Danish” with “the democratic,” using the terms synonymously. “Hence,” writes Lidegaard, “to be a good, patriotic Dane was tantamount to resisting totalitarian ideas and defending representative government, democracy, and humanism.”

The Danes defied the Nazis through their criminal code, which banned anti-Semitic propaganda “not only up to the German invasion but, remarkably, also during the occupation.” The result was “a strong sense . . . of a national ‘we,’ which included every citizen adhering to the principles of democracy and its underlying humanitarian values.” German police, aided by Danish SS volunteers, captured fewer than three hundred Jews; Danish police were given orders not to assist the Nazis.

Using diaries, journals, scrapbooks, and recollections from the children and grandchildren of the survivors, Lidegaard pieces together the harrowing stories of the refugees as they were hidden, smuggled, and finally transported to Sweden, which had bravely ordered its small navy to repel German vessels. As one Danish “helper” put it, “Our only real asset in the fight against the Gestapo . . . was our will to help the persecuted.”

One refugee recounted having “to hold on tight” to the ship’s rails “so as not to be swept overboard.” A Jewish doctor carried a syringe of morphine to use on himself and his wife if they were discovered; in case the Gestapo had come, he recalled, “I wouldn’t have hesitated.”

The Jews had one very unexpected ally: Georg Duckwitz, a conservative German patriot and member of the Nazi Party who worked to maintain the policy of reason aimed at avoiding an escalation of violence in occupied Denmark. After martial law was imposed, Duckwitz became “a crucial liaison between Danish politicians and the German authorities,” Lidegaard writes. Duckwitz’s actions may have filtered down to German police and soldiers, who had in many instances looked the other way as Jews escaped.

A Swedish doctor who treated many of the evacuated Danish Jews recorded in his diary that “they reported that the Danish people did everything to help, and that the German soldiers wanted to see them slip through.” The German police’s lack of enthusiasm, Lidegaard concludes, “was due neither to a lack of manpower nor to one of capacity. It was due to a lack of will.”

In the final analysis, Lidegaard writes, “the escape of the Danish Jews was possible because they acted on their own initiative when warned of the impending threat against them.” And what made the mass evacuation possible, he continues, “was the fact that Danish society as a whole had so quickly, so consistently, and with such determination turned against the very idea underpinning the persecution of their fellow countrymen.”

It’s a shame that the epic story of Countrymen had to wait so long to be told in full-length book form. On the other hand, we are fortunate that Lidegaard persevered in pulling together so many disparate sources to reconstruct this heroic saga. And it’s especially moving to see him connect with the last of the children who escaped with their parents—as he notes, they well understand “that they constitute singular contemporary and personal witness to the making of a miracle.”

Allen Barra writes about books for American History magazine and TheAtlantic.com.