For most of Stax Records’ initial run, from roughly 1961 to 1975, its headquarters on Memphis, Tennessee’s McLemore Avenue was the capitol building of southern soul. It wasn’t just a record label, but the headquarters of a creative movement: the place where an integrated (in multiple senses) cluster of artists and businesspeople created a new kind of popular music, sold it to the world, and tried to unite their divided community by example.

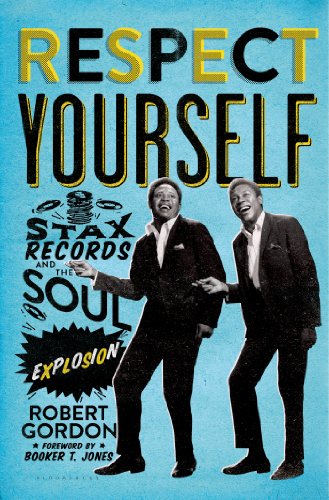

That’s a compelling story, and Robert Gordon’s well placed to tell it: He’s a historian of Memphis music, and the codirector of a 2007 PBS documentary about Stax, which, like his new book, is called Respect Yourself (after the Staple Singers’ 1971 hit). It’s also a story that’s been told before, notably in Rob Bowman’s 1997 book Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records. Bowman was more concerned with the record-by-record history of the label; Gordon focuses more on the evolution of Stax as an organization, and touches on what Stax’s success at the time meant for Memphis and for the civil rights movement across the nation.

Despite Respect Yourself’s subtitle, there’s not much here about Stax’s sound in the context of the ’60s and ’70s “soul explosion”—the musical arms race that drove black American pop forward from the dawn of Motown to the rise of disco. Where Gordon digs deeper, though, is the story of the people behind Stax, beginning with Jim Stewart, the white country fiddle player who created one of the great R&B labels, saw it through to its peak of success, and was ultimately dragged down by its crash.

Stewart launched Satellite Records in 1958 to put out a country single called “Blue Roses,” by the forgotten Fred Byler; shortly thereafter, his sister Estelle Axton joined him as a business partner. Axton and Stewart had a bit of success recording various local Memphis artists, and set up shop in a shuttered movie theater in a racially mixed neighborhood on the south side of the city, putting under one roof a label office, a recording studio, and a record store where Axton could keep an eye on what kids were listening to. Carla Thomas, who would later become known as the Queen of Memphis Soul, and her father, Rufus, heard about Satellite from a postman; they dropped by unannounced, and ended up recording a couple of successful songs there.

When Carla Thomas’s “Gee Whiz” caught on in 1961, Stewart made a handshake deal for national distribution with Jerry Wexler from New York’s Atlantic Records. Wexler came to Memphis to visit and found a city so segregated that there wasn’t a restaurant in town that would serve both the white businesspeople and the black musicians. The group resorted to meeting in Wexler’s hotel room and ordering room service—which resulted in the police banging on Wexler’s door.

Racism drove nearly everything in Memphis at the time, Gordon suggests, but the no-big-deal attitude toward race at Stewart and Axton’s label (which changed its name to Stax in 1961) allowed them to have one stroke of luck after another. Axton’s son Packy was a hard-drinking screwup who started a band with some solid local musicians; after Estelle convinced them to change their name from the Royal Spades to the Mar-Keys, they had a national hit with the instrumental “Last Night.” A cluster of the studio regulars (some white, some black) started playing together as Booker T. & the MG’s, and quickly became the Stax house band.

With keyboardist Booker T. Jones and guitarist Steve Cropper leading the way, Stax records barreled out of radio speakers. Their dance tracks led with in-your-face horn sections and constantly tossed their hooks back and forth between instruments; their plaintive, swaying ballads hinted at the musicians’ years of listening to the Grand Ole Opry and Dewey Phillips’s free-form WHBQ radio shows. Stax, in those days, was still a tiny, casual company, and they’d audition strangers who wandered in. One day, a driver named Otis Redding, who’d brought another act to the studio, asked Cropper to let him sing, and ended up recording his first single: “These Arms of Mine.”

The hits kept flowing in, and kept crossing over from R&B to the pop charts: Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood,” Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man,” Carla Thomas’s “B-A-B-Y,” the Bar-Kays’ “Soul Finger,” Rufus Thomas’s “Walking the Dog,” and one phenomenal Otis Redding single after another. The Stax artists even traveled to Europe together. At marketing director Al Bell’s suggestion, Stax’s producers shared a pool of royalty money, to encourage them to help out on one another’s records.

Everything was going great—and then everything fell apart. In December of 1967, Redding, who’d become Stax’s biggest artist, was killed in a plane crash along with most of his band, the Bar-Kays. The following April, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered at the Lorraine Motel—a favorite hangout spot for Stax affiliates. Meanwhile, the label’s distribution deal with Atlantic collapsed, and Jim Stewart discovered that, thanks to a document he’d signed without reading it carefully, Atlantic owned all of Stax’s master recordings up to that point, and had Sam & Dave under contract to boot.

Miraculously, Stax rebounded. Stewart sold the company to Gulf & Western, and gradually ceded control of its day-to-day operations to Al Bell. (Axton, who didn’t get along with Bell, was bought out.) Johnnie Taylor’s double-platinum hit “Who’s Making Love” demonstrated that the label was still in fine shape. And a lot of new employees entered the picture, including a security guy named Johnny Baylor, who is unambiguously the villain of the second half of Respect Yourself.

Baylor generally solved problems by waving a gun at them; that was useful when, for instance, thugs started hanging around near Stax’s headquarters. (Gordon quotes Baylor’s “right-hand fist,” Dino Woodard: “We let them know that, hey, they cannot bother the artists because it disturbed the mentality of the mind.”) If Respect Yourself were fiction, Baylor might just have been a goon with no sense for music; as it happens, he doubled as Luther Ingram’s manager and produced “(If Loving You Is Wrong) I Don’t Want to Be Right,” which put a certain amount of money in Stax’s coffers and, evidently, a great deal in his own.

Al Bell, meanwhile, officially became Stax’s co-owner, and set about becoming a celebrity in his own right. He had an enormous vision for Stax as an empire of American culture, and sometimes it bore fruit. The 1969 sales conference, unofficially known as the Soul Explosion, at which Bell announced a slate of twenty-eight new albums put Stax back on the map as a major pop-music force. (The breakout album turned out to be an eccentric four-song LP, Hot Buttered Soul, by a former Stax session musician who was then best known as a songwriter for Sam & Dave: Isaac Hayes.)

By 1972, Bell had built Stax into something much bigger than the little family it had once been. (That wasn’t entirely a good thing. Bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn couldn’t get into the Stax office one day in early 1972; he’d forgotten his employee ID, and a newly hired security guard didn’t recognize the man who’d played on dozens of the label’s hits.) Isaac Hayes became an enormous star, despite at least one armed confrontation between his entourage and Johnny Baylor’s. And the August 1972 “Wattstax” concert—a daylong Stax revue at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum—was a triumph (and sold a pile of soundtrack LPs and movie tickets, and made it much easier to move Stax product on the West Coast).

The label’s big records kept coming, although they dried up a little by the mid-’70s, once the scattering of Stax’s core musicians meant that there was far less of an identifiable Stax sound. (Regrettably, Gordon goes into much less detail about the creation of latter-day hits like Rufus Thomas’s “(Do the) Push and Pull (Part 1)” than about, say, earlier Stax classics like “Hold On, I’m Comin’” or “Knock on Wood.”) Everything else, though, started wobbling. CBS Records, which had never been able to do much with R&B, began distributing Stax in 1972, and their relationship gradually turned awkward, then combative.

A few months after Wattstax, financial problems hit, and Stax started drawing huge loans out of Memphis’s troubled Union Planters National Bank. Where did all that money go? It’s not totally clear, although there was, for instance, a November 1972 incident in which Johnny Baylor was stopped at an airport with $129,000 in cash and a check from Stax for another $500,000. That marked the beginning of a nine-month span during which Stax paid Baylor upwards of $2.7 million. (Gordon is drily funny on the subject: “Two million dollars doesn’t just walk out of the room. It swaggers.”) Stewart, who’d quietly left the company, nonetheless pledged his personal wealth as collateral to Union Planters.

That was unwise. By the beginning of 1975, even Isaac Hayes was suing Stax, Union Planters had seized the company’s music-publishing division, and the label was having cash-flow problems severe enough that it couldn’t make its payroll. Al Bell attempted to sell Stax to King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, who was assassinated before the deal could go through. Shortly before the end of the year, Stax was forced into bankruptcy, and armed men escorted the last remaining employees from the building.

There’s a natural temptation, when an institution that used to be good heads downhill, to find some outside force to blame. It’s reasonable to argue that the disastrous disorganization of Union Planters or the devouring capitalism of CBS or the pervasive racism of Memphis had a little, or a lot, to do with why Stax failed, and Gordon gives space to all of those arguments, as well as taking some carefully honed jabs at Johnny Baylor for swaggering away with sums greater than the rest of the company’s payroll combined. But by the time Stax closed, its ending wasn’t a tragedy. Otis Redding’s death stilled a great creative force reaching its prime, but Stax, eight years later, had completed its work—all of American R&B had already been altered by the sound that its black and white masterminds had dreamed up together in Memphis.

Douglas Wolk writes about pop music and comics for Time, the New York Times, and elsewhere.