ABOUT FOUR-FIFTHS OF THE WAY through this vast and rich omnium-gatherum of epistolary activity by Malcolm Cowley, this almost throwaway line in a letter to Yvor Winters arrives: “I’m weak, deplorably weak, in knowledge of the sixteenth century lyric.” Nobody’s perfect! The remark doesn’t come off as disingenuous; instead, it reflects Cowley’s enduring engagement (he was then sixty-nine) with verse techniques and history as both a critic and a practicing poet himself.

“Poet” ranks just above “translator” at the bottom of the multiple job descriptions usually applied to Malcolm Cowley, one of the most important and influential men of letters (or freelance literary intellectuals, if you prefer) of the twentieth century. Yet his lifelong grappling with poetic matters (he was an acolyte of Amy Lowell’s at Harvard before and after World War I) speaks to the degree, impossible to imagine in our balkanized literary situation, to which literature in its every manifestation was all of a piece to him, something he regarded in its broadest, most inclusive vistas. Declaring his aims as a literary journalist in 1944 in a grant application, he stated, “I would like to write about the books of today from the standpoint of the classics, and to write about the American classics as if they were books that had just appeared.” Which is precisely what he did over the course of an immensely influential critical and editorial career that spanned seven decades, finding the commonalities that made American writing, well, American and playing a key role in defining the canon of our national literature at points when such judgments were up for grabs.

Malcolm Cowley, who died in 1989, is nowhere near as famous or well regarded as he deserves to be, for complicated reasons I’ll get into shortly. A startling percentage of my best-read friends think I’m talking about Malcolm Lowry when I start going on about him, as I tend to do. As a young editor at Viking in 1981, I was introduced to Cowley, whereupon I experienced exactly the same feelings that Billy Crystal felt when he first met Mickey Mantle. In shaking the hand of this deaf and elderly man, I was but one degree of separation from the greats of American literature—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Cheever, Faulkner, Tate, Cummings, Wilson, Kerouac, Crane, Dawn Powell, many others—whom he knew variously as a friend, editor, critical interpreter, and occasional adversary. A couple of years before his death, I actually became his last editor, seeing into print the monumental and fascinating volume The Selected Correspondence of Kenneth Burke and Malcolm Cowley and commissioning The Portable Malcolm Cowley. So caveat lector, your reviewer is deeply in the tank.

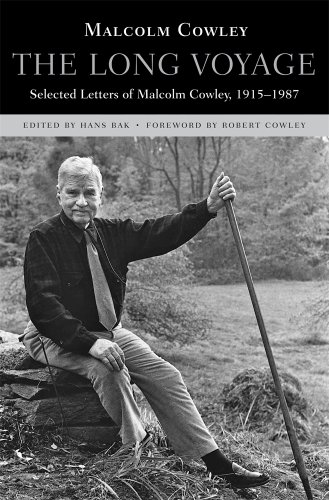

It is an index perhaps of Cowley’s eclipse in his native country that the task of winnowing through his correspondence has fallen to a Dutch scholar of American studies, Hans Bak. On the evidence of The Long Voyage, the product of editorial acuity and old-school industrial-strength scholarship, Professor Bak harbors in his capacious brain enough knowledge about twentieth-century American literature to match the English departments of any five Ivy League universities picked at random. Cowley sent letters the way today’s teenagers thumb out text messages, and Bak had to carve this 850-page book from some twenty-five thousand items residing in the Newberry Library, as well as hunt down many more letters in collections around the country. (It is exceptionally painful to learn that the letters Cowley wrote in the ’30s as the literary editor of the New Republic were all lost when their fuckwit office manager sold the files off for scrap paper—a true literary-historical holocaust.) Bak’s commentary and notes are helpful, to the point, jargon-free, and superbly well-informed, and the letters themselves have been selected and judiciously edited to form an almost biographical narrative. Because the book focuses on letters that illuminate Cowley’s involvement with both literature and politics, the private man barely makes an appearance, but that absence is more than made up for by his son Robert Cowley’s foreword, a moving act of filial piety and a shrewd assessment of the shape and significance of his father’s career.

And why should anyone produce an 850-page volume of Malcolm Cowley’s letters, and why should you care that someone did? Because, simply put, the American literature of the twentieth century would look considerably poorer and less interesting without his activities as a critic, editor, and memoirist, and our broader understanding of American literary history much less clear. Consider this partial list of Cowley’s greatest hits:

• He edited the single most important anthology in our literary history, The Portable Faulkner, the first time that any critic had fully perceived the overall unity of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County saga and assembled the pieces necessary to demonstrate it. In 1946, the year of its publication, Faulkner’s books were totally out of print; by 1949 he had been recognized as America’s greatest living novelist and was justly awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

• Gertrude Stein gave the American writers who flocked to Paris in the ’20s their indelible tag, “the Lost Generation,” but it was Malcolm Cowley who first gave his cohort its enduring narrative of rebellious escape from, and chastened return to, America in Exile’s Return (1934), a memoir and generational “collective novel” that beat Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast to the punch by three decades. We take the near-mythic saga and achievements of this generation for granted today, but as Cowley writes in his elegiac retrospective chronicle and portrait gallery, A Second Flowering, his memoir was “howled down by older reviewers [who] ridiculed the notion that the men of the 1920s had special characteristics and that their adventures in Paris were a story worth telling.”

• On July 14, 1953, Cowley wrote to Allen Ginsberg that Jack Kerouac “seems to me the most interesting writer who is not being published today.” He then undertook a dogged four-year campaign to persuade a reluctant Viking Press to overcome its editorial and legal reservations and publish On the Road. On April 8, 1957, he succeeded, concluding his on-target acceptance report in this fashion: “The book, I prophesy, will get mixed but interested reviews, it will have a good sale (perhaps a very good one), and I don’t think there is any doubt that it will be reprinted as a paperback. Moreover it will stand for a long time as the honest record of another way of life.” This Lost Generation stalwart, who knew the temper of postwar malaise and rebellion in his bones, was indispensable in the injection of the Beat Generation’s sensibility into the American cultural bloodstream, with seismic effects still being felt today.

• Three years later Cowley did something similar, writing back to Pascal Covici of Viking from Stanford, where he was a visiting instructor of creative writing, that “I’m interested in the work of a rough bird in the class named Ken Kesey. . . . [His] book may turn out to be something rather powerful.” A year later he wrote to Wallace Stegner that “we’ve taken Ken Kesey’s novel, ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S HOUSE [sic]. Much enthusiasm among the younger Viking editors. It’s interesting how the judgments on that book divide along age lines—Kesey speaks for the younger generation, and, liking his work too, I’ve been an exception among the gaffers.”

(I’m a book editor by profession, and I happen to be the same age that Cowley was when he wrote that letter. He never settled into comfortable complacency, always remaining open to the challenging and the new. Do you see why I crush on this guy?)

• Thirty years earlier Cowley had discovered another major American writer when he persuaded the New Republic, which did not do fiction, to publish the then-eighteen-year-old John Cheever’s first story, “Expelled,” a lightly fictionalized account of his expulsion from Thayer Academy. Five years later he brokered Katharine White of the New Yorker’s first acceptance of a Cheever story, and he would offer valuable career advice to Cheever for the rest of his life. In the ’30s at TNR he helped start the critical careers of such giants as Alfred Kazin, Lionel Trilling, and F. O. Matthiessen, among others, in some cases being repaid for it rather meanly years on.

And that’s just for starters, and that’s why you should care.

UNSURPRISINGLY, ROBERT COWLEY describes The Long Voyage as “a matchless portrait of the literary situation in the twentieth century” and “a significant contribution to American literary history.” Well, a son would say that, but in fact he is exactly right. Cowley arrived at Harvard from Pittsburgh in 1915, and the letters to his high school chum Kenneth Burke from that period are the usual callow pronouncements of a hyperliterate undergraduate. But in 1917 he volunteered to serve in France as a munitions-truck driver, a job shared by many significant figures of his literary generation, including Wilson, Cummings, Dos Passos, and, of course, Hemingway. Reflecting the “spectatorial attitude” he would later ascribe to that group of authors in Exile’s Return, Cowley writes to Burke of “above all seeing the events that are going to dominate the history of the world for the next century” and sharing “the great common experience of the young manhood of today, an experience that will mould the thought of the next generation.”

From 1921 through 1923, he lived in France on an American Field Service graduate fellowship, completing a thesis on, of all unlikely figures, Racine, and plunging into the thick of the Lost Generation’s Gallic adventures—the little-magazine wars, the thrilling scrapes with the Dadaists, attendance at Stein’s famed salon on rue de Fleurus. Like so many of his countrymen before and after, he found his American identity strengthened by contact with European culture, responding to a slighting letter on American vulgarity from Burke with this hilarious apostrophe: “I’m not ashamed to take off my coat anywhere and tell these cunt-lapping Europeans that I’m an American citizen. Wave Old Glory! Peace! Normalcy . . .”

Returning to New York in late 1923 to the bohemian precincts of Greenwich Village, Cowley began his ceaseless and financially precarious career as a freelance critic and journalist, a grind that would occupy the rest of his life. (A checklist of his writings published in 1975 ran to 240 pages, and he had more than a decade’s worth of activity to go.) Then as now, careerism ran rampant in this town: In 1924 he wrote to Harold Loeb that “the disgusting feature of New York is its professional writers, who are venial to the last degree. Out of business, into literature, there is nobody to respect.” From the scramble and churn Cowley evolved an efficient and transparent style, one suited to what he characterized as his “practical brain . . . [a] classical brain which builds a perfectly proportioned edifice, which writes prose that is simple and clear.” By writing reviews and essays that were built for distance and clarity rather than speed or flash, Cowley became perhaps the least quotable of our major critics, saving his wittier barbs for his letters, as in this sharp dissent on Robert Frost:

He’s a genuine Hitchcock chair, a saltbox cottage, a grandfather’s clock, a well sweep carefully preserved after the electric pump system has been installed; he’s everything nice in the antique shop, but he isn’t the voice of America.

After spending the better part of the ’20s patching together a living, in 1930 he went on staff at the New Republic as a literary editor, taking the place of Edmund Wilson, who had suffered a nervous collapse. And that’s when all the trouble began.

IN 1922 COWLEY WROTE to a friend, with in retrospect rather ominous prescience, “I have a very shallow foundation for theories on society; among literary ideas I feel more certain.” The ’30s were the radical decade in American literature, and few people who did not carry a CP membership card got as caught up as he did in the Marxist faith that artists and workers needed to make common cause. In so doing Cowley proved himself the very model of a fellow traveler—perhaps the paradigmatic figure among a group of writers and artists who made the worst possible political choices for the most idealistic of reasons. Alas, as he ascended to the influential position of TNR’s chief literary editor, he had the bulliest of pulpits to proclaim and apply that faith, in the weekly leaders he wrote and the hard left slant he gave to the review section.

How politically naive was Malcolm Cowley in those years? Naive enough to tell Kenneth Burke that “in running a book department, I’ve noticed that even unintelligent reviewers can write firm reviews, hard, organized, effective reviews, if they have a Marxian slant.” Naive enough to preach to R. P. Blackmur “that the conception of the class struggle is one that renders the world intelligible and tragic, makes it a world possible to write about once more in the grand manner.” Naive enough to write to Edmund Wilson in 1937, by which point most intelligent people had come to their senses about Comrade Stalin, of the Moscow show trials that “I think that their confessions can be explained only on the hypothesis that most of them were guilty almost exactly as charged.”

Putting such convictions into action in thought, critical word, and editorial deed, Cowley richly earned the enmity of the Trotskyite critic who called him “a cop patrolling his beat in the book review section of The New Republic with readymade memoranda drawn up for him by his Stalinist master.” Well, not exactly, but the charge stuck. As the ’30s come to a close, we see him drawing into a defensive crouch, as he justifies himself to such friends as Wilson, Allen Tate, Hamilton Basso, and John Dewey against just such charges. With the world increasingly under the threat of fascism, he cannot bring himself to openly break with a position of Popular Front solidarity. As late as 1938 he can write to Wilson, “I think that Russia is still the great hope for socialism.” As late as 1939, after the Russian-German nonaggression pact, he can write to Newton Arvin that “Stalin’s course has been admirably calculated” and refer in a letter to Van Wyck Brooks to “the immense moral prestige that communism—and through communism, Russia—has enjoyed in the western countries.” Finally, in a long and heartsick letter to Wilson in February 1940, Cowley reckons with the failure of his radical dreams and confesses, “These quarrels leave me with a sense of having touched something unclean.” Indeed, the taint of such embraces of Soviet-style Marxism would haunt him, and American intellectual life, for decades to come.

Cowley was finally cashiered from his senior position at TNR in an office putsch and relegated to the status of contributor. Recruited in 1941 by Archibald MacLeish for a position in the wartime Office of Facts and Figures (where, fascinating fact, he did some speech-writing for FDR), he came under fire as a security threat by the columnist Westbrook Pegler and then the Dies Committee, and was finally driven from DC and back to his rural fastness of Sherman, Connecticut, another instance of exile. (The letters of exculpation he was forced to write to an investigator are the saddest missives in the book.) After the war and well into the ’50s, his occasional academic appointments would stir up controversy with the John Birchers and Red Channels readers, and some of those offers would be rescinded. And of greater lasting consequence, the literary Trotskyites who morphed into the machers of the Partisan Review, and Socialists such as Irving Howe and Alfred Kazin, would demonstrate a consistent political enmity against Cowley, subtly and not so subtly reading him out of the tribe of New York intellectuals that was his natural affinity group. And Cowley knew it: As late as 1967 he worried on the occasion of the publication of his pieces from the ’30s, Think Back on Us, that he could “hear the Partisan knives on the whetstone.” No one had a longer memory than those PR street fighters.

But this exit from the fabled bloody crossroads had a happier outcome as well, in Cowley’s deepening engagement with America’s literary heritage. He replaced his discredited Marxist beliefs with a sounder, more enduring faith in what his son calls “the primacy of our national literature,” reading deeply and penetratingly in Hawthorne, Emerson, and especially Whitman. He became a leading advocate for and interpreter of American literature in all its periods, which efforts intersected fruitfully with its arrival as a fit subject for academic study. He expanded his sense of his own contemporaries as a distinct literary generation into a larger critical framework for understanding American literature as a succession of generations, each reacting against its predecessor. Knowing so many writers as intimately as he did, he brought an empirical, sometimes almost sociological approach to his consideration of their geographical and class origins, their chosen subject matters, their techniques, and the cultural and economic forces that shaped their careers. Such in-the-trenches practicality was at odds with the ivory-tower approach of the New Critics, about which he could be wryly caustic. His long association with the Viking Press bore rich fruit, including a Portable Hemingway volume that proved influential in its psychological reading of his early stories as symbolic representations of the trauma of Hemingway’s war wounds. And in the ’70s he began producing important and durable retrospective books: A Second Flowering (1973), a collation of superb portraits of his generational contemporaries (and the book that first got me on the Cowley bandwagon);—And I Worked at the Writer’s Trade (1978), a more diffuse but still valuable look back at his cohort; and The Dream of the Golden Mountains (1980), his reminiscence of and late-arriving apologia for his political activities of the ’30s. These books cemented Cowley’s reputation as both the finest and most intimate chronicler of his fabled literary generation. He even had a small best seller in a slim volume about the satisfactions and indignities of old age, The View from 80 (1980). In book terms Cowley’s final two decades were his most productive and rewarding. Many honors came to him, but only a modest portion of literary celebrity.

IN TAKING THE MEASURE of Malcolm Cowley’s career, a good yardstick to use would be that of his frenemy Edmund Wilson, for they are parallel in so many ways, from their experiences in the war to their association with the New Republic and their involvement with literary politics, to their lifelong status as critics largely independent of any particular school or institution. Wilson is unquestionably the greater figure, as a glance at his imposing shelf of books easily reveals; against such productivity Cowley’s printed and bound output looks terribly slim, with only Exile’s Return and the magical A Second Flowering really holding their own. Yet Hans Bak makes the claim in his introduction to The Long Voyage that Cowley “reached a larger audience, and so in the end perhaps did more for American literature, than such luminaries as Alfred Kazin and Edmund Wilson.” How can such a claim be substantiated? Only by a long, steady, well-documented examination of his tireless engagement with and advocacy for American writing and writers, which would reveal the cumulative positive pressure of literally thousands of influential reviews, essays, letters, and editorial decisions. The Long Voyage is an excellent and indispensable start to that process, but it is not by itself enough.

One of Malcolm Cowley’s most influential pieces of literary journalism was a long two-part profile of the legendary Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins, which appeared in 1944 in the New Yorker. Until that time Perkins was unknown to the general public as the saintly and tireless editor of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe. A. Scott Berg’s terrific biography Max Perkins: Editor of Genius (1978) brought his achievements to an even wider public, and he is now justly regarded as a hero of literature. Malcolm Cowley’s achievements are, by any measure, even greater than Perkins’s, and of more lasting influence. What is really needed to kick-start the long-delayed Malcolm Cowley revival is a similarly lively biography of the man written for the general reader, one that captures the romance and drama and, yes, tragedy of his immensely consequential life. A book that crafts a portrait of Malcolm Cowley as he truly was: the man who discovered American literature—something that in our Republic of Reinvention is in constant need of discovering. Because if you don’t reckon with Malcolm Cowley’s works and days, you can’t really understand how American literature ascended to its rightful place among the great literatures of the world, or how it was made.

Gerald Howard is an editor at Doubleday.