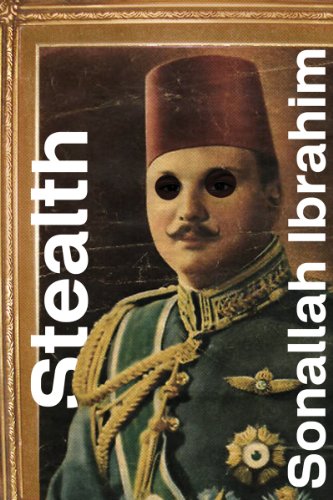

Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel Stealth begins with a mundane scene that captures the particular, weighty tedium of everyday life in Cairo:

My father stops for a second at the door to the house before we step into the alley. He raises his hand to his mouth, twisting the curved ends of his grey moustache upwards. He makes sure that his fez tilts slightly to the left. He removes the black, burnt-out cigarette from the corner of his mouth. Brushes off ash that has dropped on to the front of his thick black overcoat.

The book, first published in Arabic in 2007 and recently released in English, is told from the perspective of an eleven-year-old boy who lives alone with his father in central Cairo. The novel depicts the humdrum struggle of navigating the city and sketches a portrait of a boy dependent on his elderly father and deeply affected by the absence of his mother. Through the boy’s eyes, Ibrahim tells the story of Cairo during a time of limbo under British rule, just before the revolution that erupted after the 1948 war. It was an era when a single newspaper would be bought and shared among a circle of friends, accounts at stores were settled over time, and the occasional war siren would sound. Ibrahim presents the character of the city flatly, without comment: “A flier calls for aid for Palestinian refugees. A black banner reads: ‘No negotiations without complete British withdrawal!’ Another says: ‘Hey diddle diddle!’”

Our young protagonist recounts his days, at home, on the streets, at school, with his father. He sees poverty and debt, desire and rage. He is a watcher, observing Cairo’s streets, eavesdropping and peeping through keyholes, and, in a sense, seeking a greater truth: “I search in the rest of the drawers. A book called The Family Doctor. I flip through the pages. Twisted faces on a torn page. Another book about high prayer has the fatiha in it and some prayers of supplication.”

But most emphatically, in a narrative punctuated by memories triggered by slight gestures and fleeting moments, Ibrahim details the boy’s attempts to come to terms with his mother’s death. In a crowded city alleyway, a woman’s perfume drifts by, reminding him: “I look around for my mother. . . . I steal inside their bedroom. The bed. Across their mattress is a lace bedspread. I take the blue perfume bottle from on top of the dresser and I smell its rim.” This acute awareness of loss carries through the relationship with his father. The young boy worries, at moments, what to do about his father’s fierce temper—how can he pacify, rectify, make it go away. He also tries to soothe the fear that his father, too, will die, leaving him all alone. On a tram one day, the boy asks him how long he will live. His father replies, “To 100.”

Stealth is stripped down, a kind of literary cinema verité. The action is detailed with stately precision. The boy and his father leave their house. They greet a neighbor. They walk through an alleyway. They enter the butcher shop. They leave the butcher shop. And so on. Ibrahim conveys a keen sense of the quotidian, showing what it is like to live in times of political or personal upheaval, when it is all we can do to put one foot in front of the other. This slow accretion of details creates a sense of tension, of suspense and foreboding, as time slows down and we wait for something—anything—to happen.

The tedium, the simplicity, the curtness of Stealth might put off some readers, but the pace of it, the monotony, is what ultimately draws you in. Within that world, though we observe nothing more momentous than a boy going through his day in something like slow motion, we see a telling, compelling, nuanced portrait of a city, its people, and a lost era.

Stealth’s pared-down style marked a return to Ibrahim’s short first novel, That Smell (1966), which made his name. In that book, he told the story of a prisoner just released from jail making his way in the city and through life—a narrative borrowed from Ibrahim’s own experience as a young political prisoner set free from Gamal Abdel Nasser’s jails. Ibrahim decided to become a writer in the ’60s when he was in prison, which is where, through his discovery of Ernest Hemingway in the prison library, he developed his style. It was as much a political statement as it was a stylistic choice for Ibrahim to discard the florid prose of Arabic literature and create a language, and a form, that spoke to a time of national despair.

Stealth was decades in the making, and, as a loosely autobiographical novel, it doesn’t resemble the rest of Ibrahim’s writing, which is more overtly political. For years, the author tried to write about his father, he has said, but it was only when he reached his father’s age that he was able to complete the book; it was then that he could finally understand him. The portrait is a tender one, filled with a compassion—even for his father’s occasional outbursts—perhaps beyond the young narrator’s years.

Many have seen Ibrahim’s work as a foretelling of Egypt’s future, and Stealth can be read that way, too. It describes a Cairo that might well be the one we live in today, with familiar political and economic struggles, the same issues of power and poverty and sovereignty. Anyone familiar with Egypt’s archives knows that our history often seems to be on repeat.

Yasmine El Rashidi is an editor of Bidoun and the author of The Battle for Egypt: Dispatches from the Revolution (New York Review Books, 2011).