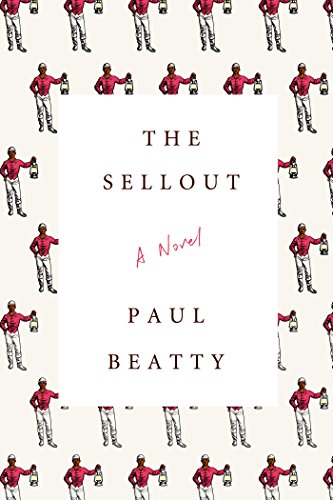

My late, much lamented friend John Leonard once wrote, “Satire means never having to say you’re sorry.” I wish John were still around for many reasons, but pertinent to the task at hand, I wish he were here to frame that assertion in the context of Paul Beatty’s audacious, diabolical trickster-god of a novel. The Sellout taunts, jostles, bites your face, and makes so many inappropriate noises at whatever passes for America’s Ongoing Dialogue on Race that it’s practically begging to be batter-fried in acrimony and censure. A scatological narrative submitted with demonic energy and angelic grace (and without any apologies, not even for leaving some of its main plot points unresolved), this damn-near-instant classic of African American satiric fiction keeps asking impertinent questions to the end, arousing those open to its subversive agenda to wonder by the book’s conclusion who’s really on their worst behavior here: The Sellout‘s narrator and alleged “sellout,” or the people in his world—and ours—who think they know better than he does how to go about getting Justice and Equality.

Consider the opening lines, placed at base camp of this slippery slope:

This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man, but I’ve never stolen anything. Never cheated on my taxes or at cards. Never snuck into the movies or failed to give back the extra change to a drugstore cashier indifferent to the ways of mercantilism and minimum-wage expectations. I’ve never burgled a house. Held up a liquor store. Never boarded a crowded bus or subway car, sat in a seat reserved for the elderly, pulled out my gigantic penis and masturbated to satisfaction with a perverted, yet somehow crestfallen, look on my face. But here I am, in the cavernous chambers of the Supreme Court of the United States of America, my car illegally and somewhat ironically parked on Constitution Avenue, my hands crossed and cuffed behind my back, my right to be silent long since waived and said goodbye to as I sit in a thickly padded chair that, much like this country, isn’t quite as comfortable as it looks.

Bet I can guess what you’re thinking: As African-American fiction goes, this cuts the hell out of “I am an invisible man, etc. etc.” for a kickoff. Well, it does, and it doesn’t. On the one hand, Ralph Ellison’s ghost can continue to rest easy in the knowledge that Invisible Man’s preeminence remains shrink-proof from even this most impudent of its progeny. On the other, Beatty’s table-setter flies past the pre-civil-rights-era abstractions laid out in Invisible Man‘s prologue and lands on a self-declaration more detailed in its post-millennial definition of black “invisibility”: It’s not that people, white, black, brown, or whatever, don’t see Me, but that they insist on projecting personality traits and low-life behavioral tics onto Me that just aren’t there.

Me, to explain that last sentence, is the only name Beatty’s antihero uses to identify himself, being, as he says, “a not-so-proud descendant of the Kentucky Mees, one of the first black families to settle in southwest Los Angeles.” Hence the case of Me v. the United States that brings him before the high court on charges related to restoring slavery and segregation. Me himself (try to keep up) has in fact tried to bring back those things, in order, he says, to save his childhood home from oblivion—or, at least, to put it back on the map.

Really, try to keep up: Me was raised in Dickens, “a ghetto community on the southern outskirts of Los Angeles” with a ten-block agriculturally zoned region known as The Farms, where, Me is obliged to tell you, “your rims, car stereo, nerve, and progressive voting record will have vanished into air thick with the smell of cow manure and, if the wind is blowing in the right direction—good weed.” His late father, an outsize wackadoodle deserving a surrealist novel of his own, was a behavioral psychologist who taught his son how to treat the land with tenderness while subjecting him, practically from the cradle, to a barrage of ruthless psychological experiments whose desired outcome remains a mystery to Me. (You tell me—lowercase—why a father would subject his son to a beating on a busy ghetto street corner to show that black people are immune to the “bystander effect”—made notorious by the 1964 Kitty Genovese case—because of their inclination to help, rather than ignore, someone in need. And indeed, they do help . . . with Dad in treating Me to an impromptu mugging. He comforts his son afterward by admitting his neglect of the “bandwagon effect.”)

Whatever the father’s intent, the cumulative effect of these abuses-in-the-name-of-science was to inure Me to any prefabricated or hidebound illusions about racial identity, pride, or solidarity. Meanwhile, the rest of Dickens reaps more fruitful benefits from Dad’s therapeutic abilities as the “Nigger Whisperer,” so called because of his ability to talk down any community member “who’d ‘done lost they motherfucking mind.'” Nonetheless, the father’s powers can’t protect him from the path of bullets exchanged in the crossfire of a deadly police shootout.

First, Me’s father goes into the ether, and then, five years later, so does his hometown, stricken from California maps due to “a blatant conspiracy by the surrounding, increasingly affluent two-car-garage communities to keep their property values up and blood pressures down.” Me pursues his father’s legacies as both farmer and “whisperer.” In the former, he becomes a fruit grower of near-legendary stature. In the latter, well, “I met interesting people and tried to convince them that no matter how much heroin and R. Kelly they had in their systems, they absolutely could not fly.” The most interesting of these, by far, is Hominy Jenkins, the last surviving member of the Little Rascals, the kiddie-comedy-film troupe of the Depression. Hominy has apparently been driven “bat-shit crazy” by years of being typecast as a bulging-eyed black foil for Spanky, Alfalfa, Darla, and the rest and wants nothing more from life than to be somebody’s, anybody’s, slave. Me, after rescuing Hominy from a “self-lynching” in the latter’s backyard, accommodates this wish, along with one more: “Beat me, but don’t kill me, massa. Beat me just enough so I can feel what I’m missing.”

I’m with you. I’d love to take a breather, but there’s too much else to tell, a lot of it having to do with Me’s attempts to get Dickens put back on the map, which is the one thing Hominy would like more from life than vigorous, pointless thrashings. After Me reunites with a childhood sweetheart, Marpessa Dawn Dawson, who’s now a certified LA bus driver, he gets the idea of reestablishing the color line on public transportation as a means of restoring civility among community residents. This emboldens him to ask the embattled local school superintendent to resegregate her public schools as a way of making them seem more competitive with under- or overperforming counterparts in surrounding communities that still have names on the map. And if you don’t think all of that is enough to dip Me in deep doo-doo, there’s the sullen derision he barely contains while gobbling Oreo cookies at the Dum Dum Donut Shop, hangout for SoCal black intellectuals, or, as Me terms them, “wereniggers,” who endorse rewriting literary classics to make them more palatable to black children. How’s The Pejorative-Free Adventures and Intellectual and Spiritual Journeys of African-American Jim and His Young Protégé, White Brother Huckleberry Finn as They Go in Search of the Lost Black Family Unit sit with you? Me neither, so to speak:

I wanted to say more. Like, why blame Mark Twain because you don’t have the patience and courage to explain to your children that the “n-word” exists and that during the course of their sheltered little lives they may one day be called a “nigger” or, even worse, deign to call somebody else a “nigger.” No one will ever refer to them as “little black euphemisms,” so welcome to the American lexicon—Nigger!

And an even bigger welcome to those who come to The Sellout without having first encountered Paul Beatty’s earlier literary carpet bombs, such as The White Boy Shuffle (1996), Tuff (2000), Slumberland (2008), and the manifestly ecumenical anthology of African American humor Hokum (2006), wherein the likes of H. Rap Brown, Mike Tyson, Al Sharpton, Franklin Ajaye, and Lightnin’ Hopkins dine at the same table as Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, George Schuyler, Darius James, and Ishmael Reed. There are also echoes of the mid-1960s Mothers of Invention, whose “Trouble Every Day” remains a half step behind Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust as a tableau of LA apocalypse. What the hell, we’ll throw Pep West’s name in this, too, along with Richard Pryor, Lenny Bruce, The Firesign Theatre, and Percival Everett’s acerbic, groundbreaking inquiries into black identity (Erasure, notably). I also found myself transported back to the early ’80s, when the Bus Boys, an all-black-with-a-Latino-drummer New Wave rock band from LA, faced down the retro racism of the Reagan era by seizing its reductive rhetoric and flinging it back in white folks’ faces with lines like “I bet you never heard music like this by spades. . . .”

And I bet they couldn’t get away with lines like that in the present day, when the public discourse on race is now lined with eggshells and everybody’s trying to tiptoe on those shells, wearing masks that make it difficult to see one another. Drop the masks! The Sellout demands. Break some eggs! Maybe in the ensuing melee, this whole wonderful world of color of ours will finally begin figuring out who and what it really is, collectively and individually. Who could be sorry for that?

Gene Seymour has written about music, film, and literature for such publications as The Nation, Los Angeles Times, Film Comment, and American History. He lives in Philadelphia and is working on a collection of essays.