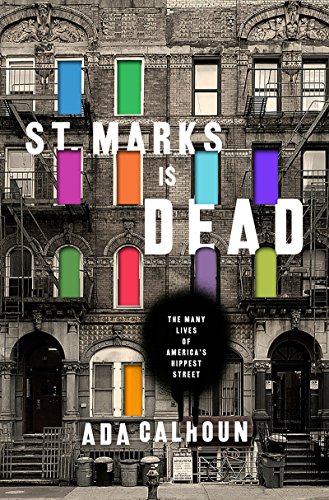

St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street (Norton, $28) has a title you might gloss over, or perhaps dismiss as an ironic aside or forgotten punk-rock lyric. Oh, but no. If we may hazard a spoiler, the upshot of this zippy history by Ada Calhoun is that whatever era of cool you’re looking for, whether hippie, gang, punk, gay poet, Victorian, German immigrant, Warholian, drag queen, or Puerto Rican New Wave, it is absolutely extinct. What’s more, it’s been replaced by something much more static and deadening than the “nothing good” that prior hipster pioneers will reliably deride: The new face of St. Marks is literally nothing whatsoever. The street that people said was over and done and uncool every decade for at least a century is, at last, a mausoleum.

Any honest history of the location of counterculture in America would say the same. I don’t know if you’ve checked in on the Haight-Ashbury recently, but if not, I have some chilling news for you: Your laid-back hippie wonderland is now a moneyed preserve of condominiums and bland, plutocratic Internet smugness.

What do we do now? And, as an equally unsettling corollary: Who are “we,” nowadays? Are there countercultures in our cities, in any kind of physical space? The very idea of a gay neighborhood is dying, mostly by choice. Both historically and recently, black urban neighborhoods are being whitened in a more complicated way. There are few physical grounds to contest. The inexorable creep of gentrification does not result in fireworks. Maybe the next great real-estate dustup will occur when young professionals at last invade the enclaves of the Hasidim.

Perhaps countercultures, having mostly migrated to the Internet, are now more inclusive and tamely organized. The shared space of political passions or (more commonly) clashing trendy outlooks that would occasionally explode into violence typically gets channeled into the stylized discontent of a snippy Tumblr reblog. That might not be the worst thing. The actual violence was, like, uncool, man.

In any event. At no time does 92 St. Marks Place show up in Calhoun’s meticulous book. Once managed by the Lebewohls, who owned the Second Avenue Deli, it was among the most crumbling of tenements. The rent was $1,500 for a floor in the mid-’90s, when I moved in. This was already a travesty, of course, but by the standards of New York real estate, it didn’t qualify as outlandish.

The rent will always have been cheaper. “In 1975, I lived on St. Marks with four rooms and a fireplace for $125 a month,” a bookstore owner named Bob Constant tells Calhoun. (That’s just $552 when adjusted for inflation.) “We were getting $2.50 an hour. You could afford your own apartment. There were cheap restaurants where you could go on a date. There wasn’t a stigma about being poor. Everybody was poor.”

This is the story that echoes down through the past four decades. What becomes of a city in which no one can really afford to live? After all, the ground floor of 51 St. Marks Place was $85 a month in 1951—$777 in today’s dollars.

Ninety-two St. Marks was also the site of one of the first parties I’d ever been to in New York, a bohemian affair of some cultured and hunky young gays along the axis occupied by Stephin Merritt and John Cameron Mitchell. All artists, and all clearly poor. We were told that at one point the apartment had been a locus of some long-failed East Village magazine. There was sprawling charm, moldings, and filth. The occupants kept their bed in the front room, where the bus soot and noise billowed in. When I moved in, some years later, I kept mine in the back. By the time I left, quite suddenly, my lease for that same apartment was $2,300 and there was a landlord’s proposal on the table for $2,600. Upstairs, Dale Peck would stay not much longer; Sia Michel, now the New York Times’ Arts & Leisure editor, was already gone. Last year, the apartment burned down, but this year it was resurrected, with all the grace of the most ghastly Home Depot renovation. “Massive and very charming 3 bedroom 1 bathroom unit on famous Saint Marks Place,” said the ad. It went on the market for $4,950 and was snapped up immediately. Zombie St. Marks Place: It’s alive.

“I will always love the East Village and how it allowed me to pretend to be what I was until I could finally muster enough nerve to finally try and actually become it,” New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz tells Calhoun. When I moved to Eighth and Avenue B in the early ’90s, he lived around the corner, in the neighborhood’s only tall building, the besieged Christodora, a site of class resentment so furious that people stood outside to scream at residents. (This never happened at the High Line!) Saltz’s sentiment, perhaps the most earnest in the whole book, is wholly true. There was space, collaboration, wildness, and closeness enough to function as a kindergarten for adulthood. Are Bushwick and Ridgewood able to make that true for younger people now? I suspect the new New York neighborhoods of artists and writers and musicians are too isolating and isolated to serve. And so, as Calhoun’s history copiously and sadly documents, the richer city is all the poorer.

Choire Sicha is the author of Very Recent History (Harper, 2013).