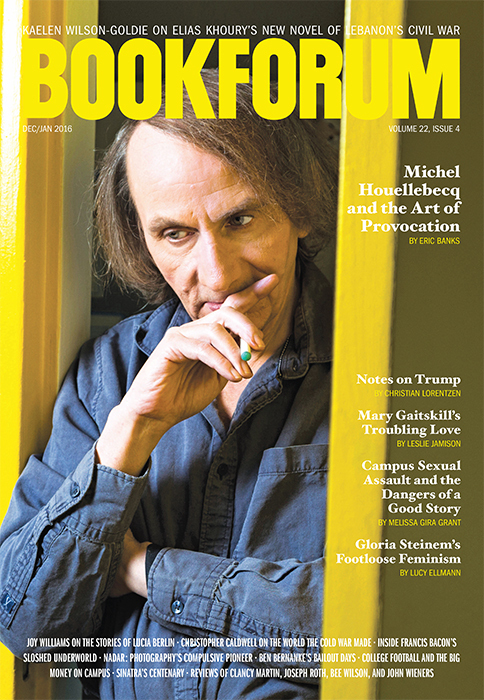

For some time I’ve wondered how Michel Houellebecq’s Submission would play when it arrived here in the States, nearly a year removed from its tumultuous publication in France. In that country, of course, it appeared the same morning that terrorists slaughtered much of the editorial staff of Charlie Hebdo, including one of Houellebecq’s closest friends. The book had already enjoyed—if that is the right word, and with Houellebecq it probably is—a prepublication patina of infamy. The novel dominated the evening-TV pundit fests, sparking debates about multiculturalism, Islamophobia, and the politics of provocation and responsibility. Fleur Pellerin, the embattled minister of culture who had just recently flubbed a test of her literary credentials by not being able to name a single book by Nobelist Patrick Modiano, vowed that she would most definitely read Submission. François Hollande promised that he would too. And this happened before the massacre.

In America (and in the UK, too, where Submission was recently published), the novel arrives with its context neatly packaged in hindsight: Without the notoriety of the January attack, I’m not convinced that the appearance of Submission would have occasioned much in the way of readership or discussion. (In Germany and Italy, the book was on the shelves and out the door almost immediately, with sales figures rivaling those in France.) It’s been aeons since a novel by Houellebecq raised so much as an eyebrow, much less moved the cultural needle—ask yourself how frequently The Map and the Territory, which garnered Houellebecq the Prix Goncourt, popped up in have-you-read-it conversations. At least in the States, he has occupied a position somewhat analogous to, say, that of Lars von Trier, another prematurely discolored, self-conscious enfant terrible with an agonistic relationship to his artistic and political forebears, whose occasional creative brilliance is undercut by a penchant for vapidly offensive statements. That is to say, both are shticky performers with a predictable brand, and more often than not easier to ignore than to care about.

For those who have missed the past decade of his work, Submission is a recognizably Houellebecqian production, rendered by translator Lorin Stein in admirably lucid prose and with a sensitive ear for the author’s humor. A slew of dystopianism leavened by sharp slices of comedy, with a plot punctuated by the seemingly obligatory flight from Paris to a moribund French countryside, Submission delivers an antihero who will be familiar to readers of Houellebecq’s earlier novels, a depressed and lonely intellectual whom one might call disillusioned had he ever once demonstrated the slightest touch of illusion. The book also traffics in an appallingly casual misogyny that is at once grotesque and gratuitous, even by Houellebecq’s standards. Contrary to the advance billing, what plagues Submission isn’t Islamophobia—the novel is actually quite gentle, even welcoming, in its attitude toward Islam—but its Neanderthalish sexual politics. If anything, Submission’s coupling of an unapologetically ugly and hateful worldview with a clearly satirical and often funny vision makes it somehow more of an unholy mess of sharp observation and sloppy stereotype than his past work.

The ambiguities of Submission make for an unsettling reading experience. Alongside the reflexive nastiness, there are several inspired gestures here. Prime among them is to make his protagonist, François, a forty-four-year-old professor of literature, a specialist in the work of J. K. Huysmans. A bibulous bachelor whose intimate life lurches from term to term in casual affairs with his students (which usually end with the unsurprising notice that they have “met someone”), François leads a bleak existence of TV dinners and Internet porn. He loathes his mediocre colleagues and has no contact with his parents, who live somewhere deep in the provinces. But in Huysmans, whom he first read in the years of his “sad youth,” he has found something almost greater than “a faithful friend.” It is a strange form of companionship, and one that François articulates very early in the novel in an oddly moving defense of the written word:

Only literature can put you in touch with another human spirit, as a whole, with all its weaknesses and grandeurs, its limitations, its pettinesses, its obsessions, its beliefs; with whatever it finds moving, interesting, exciting, or repugnant. Only literature can grant you access to a spirit from beyond the grave—a more direct, more complete, deeper access than you’d have in conversation with a friend. Even in our deepest, most lasting friendships, we never speak so openly as when we face a blank page and address an unknown reader.

Is this François speaking, or is it Houellebecq? Is the soliloquy of a piece with the character’s severe anomie? Is it a user’s manual to Submission or a mea culpa by its author? As François’s journey through Submission will mimic the biography of Huysmans and his arc from decadent author of À rebours (and inspiration to Oscar Wilde) to mystical Catholic convert, the ambiguity of what counts as “literary conceit” and what doesn’t is among the novel’s more provocative aspects. The otherworldliness of the connection also pardons the extreme solipsism and obliviousness of Houellebecq’s creation, who finds himself dropped into some of the most momentous changes in the history of France.

The plot of Submission is split in two, with a before and an after not uncommon in stories of conversion—though Houellebecq’s division has as much to do with political events in a future France as with the spiritual autobiography of François. It is 2022, an election year, and the far-right National Front party’s share of the vote has grown to 34 percent. The Socialists cling sclerotically to power, but a new party—the Muslim Brotherhood, led by a charismatic candidate, Mohammed Ben Abbes—has enjoyed monumental growth and poses a real threat to the political establishment. As a stupefied François follows the results, the Brotherhood squeaks past the Socialists and sets up a showdown between an insurgent Islamic party and the fascist nativists of Le Pen and co. Suddenly, armed militia are lurking on the outskirts of Paris. At a party for his colleagues, François hears gunshots in the distance and awakens to a new reality:

The idea that political history could play any part in my own life was still disconcerting, and slightly repellent. All the same, I realized—I’d known for years—that the widening gap, now a chasm, between the people and those who claimed to speak for them, the politicians and journalists, would necessarily lead to a situation that was chaotic, violent, and unpredictable. For a long time France, like all the other countries in Western Europe, had been drifting toward civil war. . . . But until a few days before, I was still convinced that the vast majority of French people would always be resigned and apathetic—no doubt because I was more or less resigned and apathetic myself. I’d been wrong.

He decides to ride out history in the French countryside—and conveniently ends up in the historic town of Martel, named after the medieval Frank who decisively defeated

the Arabs.

Part two, as it were, begins with the civil war that never quite comes. The wave of electoral violence that sweeps the country leads the Socialists to support the Muslim Brotherhood, which narrowly wins the election. Their unusual pact results in an unusual exchange of portfolios—Ben Abbes is more interested in taking control of education and family law than anything else, and soon religious education and polygamous marriage are legalized. Astonishingly—certainly to any reader who would buy Houellebecq’s vision as even borderline realistic or prescriptive—a reign of optimism unseen since the election of Mitterrand sweeps the country. Sectarian violence disappears, crime rates drop to nearly zero, and unemployment becomes a thing of the past (helped, no doubt, by the fact that women are no longer in the workforce). The Sorbonne is purchased by the Saudis and becomes open only to those of the faith. This means that François returns to Paris without a job. Relieved of the one activity that kept him going, he drifts even more aimlessly.

As political theater, Houellebecq’s fantasy is certainly preposterous (though would it be less so if his satire included a reality-show casino magnate, a failed tech CEO, or a neurosurgeon who had gone out of his way to argue that Muslims should be barred from seeking the presidency?). So too is the particular avenue for salvation available to François: conversion to Islam, brokered by the new president of the Sorbonne, himself an expert on Nietzsche and a convert, who in an inspired gesture inhabits the hôtel particulier once home to the literary titan Jean Paulhan, whose midcentury reign over the Nouvelle Revue Française couldn’t be more anathematic to the Houellebecqian agenda. It was here that Pauline Réage’s Story of O was composed, with its own drama of eroticized submission. But Submission plays constantly on an ambiguity between reality—political or otherwise—and farce. The latter often enough dominates the action. This is a cartoon world, albeit one populated by real political figures and easy-to-imagine bureaucratic mediocrities. Even the question of what it means for François to convert to Islam seems to boil down to the fact that he’ll be able to count on the convenience of a bounty of wives and a plum Sorbonne job with a fat paycheck. Houellebecq’s notion of Islamic conversion—nothing to lose, and a world to gain—reveals the depth of his theological investment.

It’s a particularly fickle turn given how profoundly he writes about the blocked path to Christian conversion facing François, which is where Submission is most fascinating. The twin themes of the purported failure of the secular social order and the various ways one might escape this gloomy world have captivated Houellebecq since his very first literary forays (in The Map and the Territory, he suggested the ultimate escape when he murdered off a character named Michel Houellebecq). The most interesting moments of Submission are those in which the routes open to François to fulfill his Huysmans-esque conversion fail him. At the Catholic pilgrimage site of Rocamadour, he spends days in attempted devotion to the Chapel of Our Lady and the Black Virgin, but the rapture fails to come. Later, he withdraws from Paris to the abbey near Poitiers, where Huysmans himself escaped into mystical Catholicism. François lasts for three days before giving up. It’s tempting to read the futility of his gestures as running parallel to a kind of failure of literature as much as of religion, of a “faithful friend” letting François down. Waiting for the TGV to take him back to Paris, he heads for a local tavern. “The waitress was thin and wore too much makeup. The other customers were talking in loud voices, mainly about real estate and vacations. It gave me no satisfaction to be back among people like myself.” It’s as if François, in search of the miraculous, finds himself stuck in a Houellebecq novel.

Eric Banks, the former editor in chief of Bookforum, is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU.