The great Moroccan writer Abdellatif Laâbi was just twenty-three years old when he met the poets and painters who would help him revolutionize the worlds of art, literature, and politics across North Africa and the Middle East. It was 1965, and Morocco was poised between a once-promising independence, which it had won from France nine years earlier (only to see it diminished by the restored monarchy’s crackdown on dissent), and the “years of lead” (zaman al-rasas), which would stretch into four decades of increasingly brutal repression under the reign of King Hassan II. It was also the height of the Cold War, and a striking moment of convergence among wildly different left-wing liberation movements all over the world.

Laâbi was the son of a craftsman and a housewife who bore eleven children (eight of them lived). Neither of his parents learned to read or write. He was raised in the labyrinthine medina of Fez and spent his formative years in a house without books. Even so, he fell in love with the possibilities of language—first with the rich imagery of the stories his mother told him in Arabic, then with the sounds and structures of French, which he learned in school. By the time he finished university in Rabat, Laâbi was writing poems and publishing them in small, obscure journals. The smallness and obscurity of those journals irked him, as it did Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine and Mostafa Nissabouri, two Casablanca poets who were publishing their work in a car magazine for lack of better options. Laâbi sought them out. They, in turn, introduced him to the painters Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Chebaa, and Mohamed Melehi, who were teaching at Casablanca’s École des Beaux-Arts and would later be regarded as the foremost modern artists of their generation.

All of them were feeling their way toward a common political goal, which was to use their experiments in art and culture to remake their country, free it from the colonial past, fend off a neocolonial future, and find their own way forward. They were inspired by a strong dose of Marxist-Leninist doctrine and spurred into action by the real-life atrocities that were happening around them. The Moroccan opposition leader Mehdi Ben Barka disappeared in 1965, two years after he’d been forced into exile and three months before he was supposed to open a major conference in Havana that sought to align the globe’s disparate Third World revolutionary movements. The same year, King Hassan II declared a state of emergency and suspended the Moroccan parliament, and thousands of students were killed while demonstrating for greater access to higher education. That Laâbi and his cohort chose a print journal as their medium says something about their time, about the proximity of the avant-garde to public discourse and the potential of a daring literary venture to reconfigure mainstream culture from within. That it has taken nearly fifty years to anthologize their efforts and reconsider their works probably says something more about our own time, given how necessary such a project has become in the aftermath of the Arab Spring—and how remote it seems today.

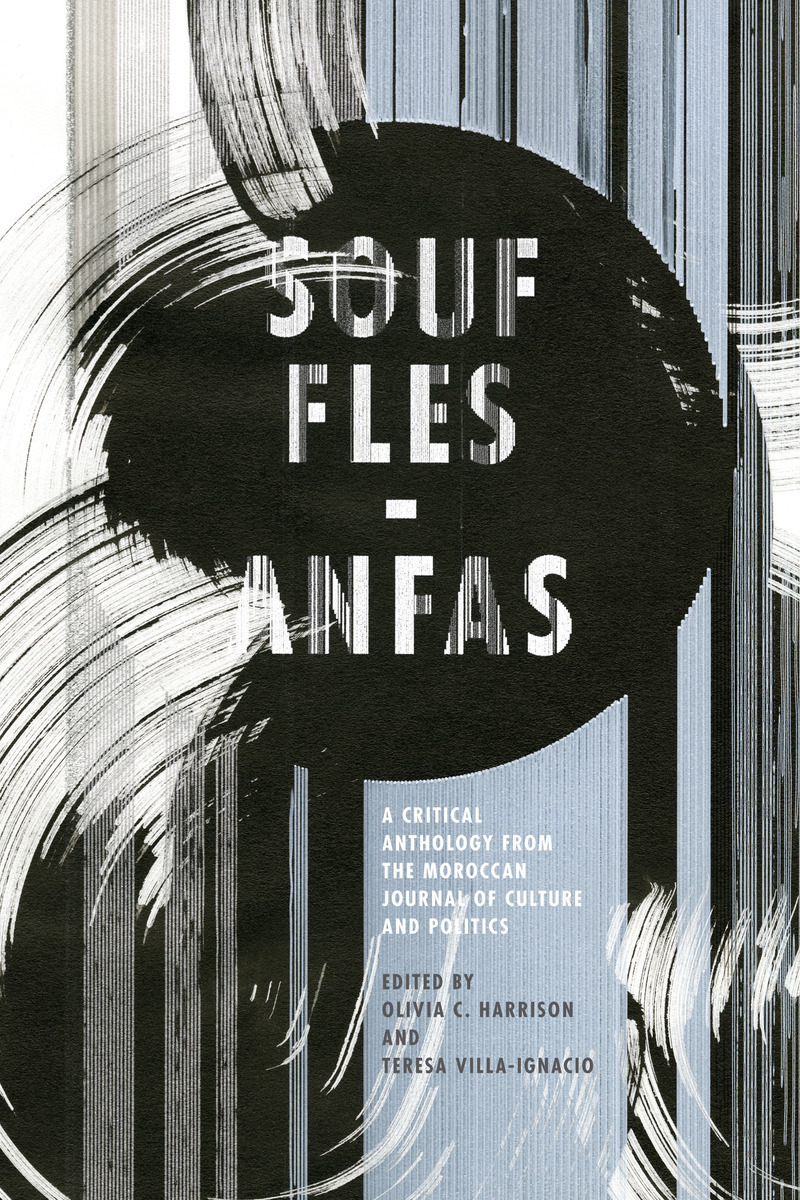

In the spring of 1966, Laâbi launched the first issue of a new magazine called Souffles, French for “breaths” or, idiomatically, “inspirations.” Melehi designed the logo, rendered in block letters above a blazing, monochromatic sun. Chebaa handled the art direction; Belkahia did illustrations. In time, the original group of poets and painters expanded its numbers beyond Morocco’s borders to create the magazine’s unique editorial “action committee.” Heavily indebted to Frantz Fanon’s notion of cultural decolonization, they wrote manifestos calling for the total reinvention of Moroccan art, literature, and cinema. In those texts, they urged one another, as well as their readers, to abandon the forms they knew from colonialism and from Europe for writing novels and poems and for conveying knowledge of the country’s cultural history. They argued for a critical reassessment of the past—returning to the visual elements of abstract Moroccan painting, for example, or to the poems and songs of folklore, to find forms that had been previously dismissed as primitive but could now be fashioned into something new. They also argued for the creation of a language of emancipation, pieced together from Arabic, Berber, and French and incorporating the revolutionary rhetoric of oppressed groups around the world. They published the Haitian poet René Depestre and the Syrian poet Adonis; ran essays by Amílcar Cabral and Mário de Andrade, charismatic leaders of the independence movements in Guinea-Bissau and Angola, respectively; and reprinted the Black Panther Party’s enduring ten-point program (“We want freedom. . . . We want full employment for our people. . . . We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace”).

Early issues featured a damning critique of Négritude, arguing that Aimé Césaire’s once-radical literary movement had lost its edge when Léopold Sédar Senghor became the president of Senegal and turned it into a folklore festival and tourist attraction. The magazine also included the first, shy poems of the now-famous Moroccan novelist Tahar Ben Jelloun; early caricatures by the Tunisian-born French cartoonist Georges Wolinski, killed in the Charlie Hebdo massacre last year; a chronology of Moroccan painting since independence in 1956; analyses of world cinema and the oral traditions of vernacular poetry; and a wealth of impolite reviews and rambunctious interviews. These early issues were often both funny and elegant, scrappily produced and sophisticated in their arguments and in the pacing of their essays, poems, and artworks. Laâbi, in particular, used the pages of Souffles to return to (and critically revive) the work of an older generation of writers, namely the Algerian novelist Kateb Yacine and the Moroccan novelist Driss Chraïbi. (In doing so, Laâbi insisted on a close rereading of these authors and a reassessment of their politics. At the time, many of his generation would have been content to write that work off as francophone and prerevolutionary, and therefore compromised, or too complicated, in its position.) He also wrestled endlessly, agonizingly, with the fact of writing in French, the colonizer’s tongue, while fighting for a new national culture ever more committed to expressing itself in Arabic.

The staggering defeat of 1967—when Israel swiped the Sinai from Egypt, the West Bank from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria during the Six-Day War—stunned the Arab world and radicalized the staff of Souffles. Laâbi and Co. published a special issue on Palestine, got rid of Melehi’s elegant cover design, and replaced it with war-torn photojournalism and political-campaign posters. A number of the original poets and painters resigned to protest the magazine’s sudden political turn. The youthful tone and jumbled energy of the early poems and confessional texts (such as the Tunisian novelist Albert Memmi’s “Self-Portrait,” about his failures in love and literature) gave way to a style of writing that was often either dry and technical or overheated with revolutionary fervor and politically bombastic. The imagery also changed, as geometric and gestural abstractions gave way to Kalashnikovs and other such weapons on one magazine cover after another. Then, in 1968, the inimitable Abraham Serfaty, sixteen years Laâbi’s senior, joined the editorial board. A prominent member of Morocco’s middle-class Jewish community, Serfaty was dangerous to the monarchy on all counts: He was a phosphate-mining expert in a country rich in natural resources, a card-carrying Communist, a hero of Moroccan independence who had been arrested and exiled by the colonial regime, a labor organizer, and, most damningly for the regime of King Hassan II, an incendiary advocate for the independence movement in the Western Sahara.

In 1971, under Serfaty’s influence, Souffles launched a sister publication in Arabic called Anfas. Within a year, the government had shut down both magazines. Laâbi and Serfaty were thrown in jail and tortured. Their work—in publishing as well as in the founding of the underground political party Ila al-Amam (“Forward” in Arabic)—had become so popular by then that a large number of students protested their arrest. They were released, but only temporarily. Laâbi was promptly rearrested and imprisoned for eight years, accused of conspiring against the state. He was freed in 1980, along with forty-five other political prisoners described by the regime as “extreme leftists.” Five years later, he was forced into exile. Since then, Laâbi has lived in France, returning to Morocco only briefly but writing beautifully, prolifically, and above all ruefully about his childhood (in the tenderhearted novel The Bottom of the Jar, published in 2002) and the loss of his country (in the marvelous and forceful 1996 poem cycle “The Spleen of Casablanca”). Serfaty, meanwhile, went into hiding. In 1974, he was caught, jailed, and given a life sentence. Under international pressure, the regime released him in 1991 but stripped him of his Moroccan citizenship. When King Hassan II died in 1999, his son, Mohammed VI, restored Serfaty’s citizenship and offered him a job as a special adviser to the king. Although he still agitated for democracy and social justice, Serfaty took the job, which he held until his death in 2010.

Altogether, Souffles lasted just six years and published only twenty-two issues (Anfas published only eight). The print run never exceeded five thousand copies. The office never moved from Laâbi’s apartment, no one made any money, and the magazine never even covered its costs. But like its political consequences, its cultural reverberations were legendary in their time and have remained so for decades.

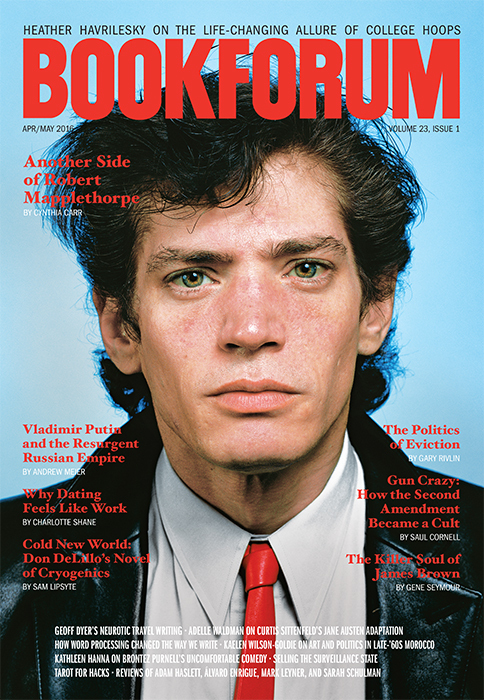

Since leaving Morocco in 1985, Laâbi has mostly kept his distance, but he is nevertheless regarded as a national treasure these days. Five years ago, he made a deal with the curator of Morocco’s National Library to scan and preserve complete back catalogues of Souffles and Anfas and make them available for free online. That archival effort is a gift to academic researchers and lay readers alike. So, too, is the new volume Souffles-Anfas: A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics, edited by Olivia C. Harrison and Teresa Villa-Ignacio, which cuts into the corpus of both magazines and—thanks to a small army of seventeen translators—makes a slice of the material available in English for the first time.

The anthology tells the wonderful-sad story of Souffles and Anfas in some three hundred pages, and mostly lets the magazines speak for themselves. Harrison and Villa-Ignacio have kept their introductions brief, devoting most of the book to selections from the publications. Divided into four parts, the anthology proceeds chronologically. The editors have gracefully reconstructed the narrative of Souffles’ political radicalization, most apparent in Laâbi’s texts on the journal’s role in remaking the national culture, which repeat throughout the book in an increasingly urgent—and increasingly violent—refrain.

“Something is about to happen in Africa and in the rest of the Third World,” Laâbi writes in his prologue to issue 1. “Exoticism and folklore are being toppled. No one can foresee what this ‘ex-pre-logical’ thought will be able to offer to us all. But the day when the true spokespersons of these collectivities really make their voices heard, it will be a dynamite explosion in the corrupt secret societies of the old humanism . . . . Souffles is not here to swell the ranks of ephemeral journals. It responds to a need that we can no longer ignore . . . . Poetry is all that is left to man to reclaim his dignity, to avoid sinking into the multitude, so that his outcry forever carries the imprint and attestation of his inspiration.”

Later, in a critique of the colonialist daily newspaper Le Petit Marocain, Laâbi adds: “Our journey has only just begun. We have not yet come up against the cyclical butchery of values, against the impasses that lead certain civilizations towards apathy or absolute skepticism. We are at the stage of reconsolidation, of rediscovery. We are on the threshold of speech that has not lost its meaning for us.”

By the time we cross into the 1970s, Laâbi’s tone is changing:

I will say it again. Enough! Read us according to what we are, according to the project whose foundations we are patiently, modestly, and freely trying to lay, and which we invite you to debate and enrich . . . . Maghrebi literature has broken through the wall of silence . . . This literature has assumed responsibility for the necessary step of clearing, dynamiting, and reconstruction that is coursing through our culture. Many will feel confused . . . . [P]articipate, through your active, adventurous reading, in the work. Recreate it. Do not judge our literature based on your accumulated culture.

By the end, Laâbi is likening the writing of North African literature in French to terrorism, an action that “shatters the original logic” of the language. In the final issue, he surrenders, saying the use of the French language has “flagrantly compromised” the very ideals of Souffles,and strains somewhat to explain the appearance of Anfas and the need for both magazines to narrow their focus to Morocco and the Arab world. “This is the meaning of our new struggle,” he concludes.

Some of the best moments in the Souffles-Anfas anthology occur in the interviews the contributors conducted with literary elders and peers from the fields of film and theater. Their subjects include Ousmane Sembène, a filmmaker and former trade unionist who wouldn’t let a trite comment about cinema in the streets pass and insisted on relentless pragmatism in art and politics alike; Jean-Marie Serreau, a theater-maker who challenged some of the simplistic binaries between East and West that Souffles was concerned with, only from the other side, staging works by Kateb Yacine, Aimé Césaire, and René Depestre in Europe; and Driss Chraïbi, a writer who belonged to a generation of novelists who had been popular in Morocco’s pre-independence era but were later cast aside for being elitist and premodern, for using aristocratic and colonialist forms, for addressing the bourgeoisie, and for leaving the country at a moment of revolutionary possibility instead of sticking around to fight. It has become rare to read interviews—nowadays so carefully manicured and maintained—shot through with real tension and flares of argument, as when Chraïbi says to Laâbi: “How surprising to hear your limited reading [of my work]. You’re free to do as you wish . . . . But I have too much regard for you and your journal to let this opportunity for dialogue pass.” Then he rips into the younger writer’s alleged misinterpretation of his latest novel, barreling into a wholly unexpected defense of women’s rights (“But tell me, isn’t woman, wherever she happens to be, the last remaining colonized being on Earth?”).

On that note, one of the most striking things about the new anthology is the staggering weakness it lays bare in the Souffles legend: In twenty-two issues, Laâbi and his cohort published the work of women writers exactly three times, and never again after issue 8. One of the women contributors was the now nonagenarian wonder Etel Adnan, whose poem “Jebu”—composed in French when she was in her early forties and published around the same time in the Iraqi poet Sargon Boulus’s like-minded journal, Tigris—was written for Palestine in the wake of the war of 1967. Another was Jeanne-Paule Fabre, author of a piece about Moroccan women’s writing. And the third was Toni Maraini, an Italian art historian (also Mohamed Melehi’s wife) who offered an essay about Moroccan painters—all of them, as it happens, men. The exclusion of women’s voices and women’s concerns isn’t incidental. It was repeated in similar projects throughout the region, in the Cairo magazine Al-Hilal and the Beirut journals Shi’r (Poetry) and Muwaqif (Positions), edited by the poets Yusuf al-Khal and Adonis. It is precisely this imbalance that accounts for the failure of Laâbi’s efforts in the long run, and it explains why so many of the era’s political projects did not actually reconfigure the world, or a particular society, as a better, more just and equitable place.

What else is missing from Souffles-Anfas? A sense of what the magazine actually looked like in its original form: the fonts, layouts, mistakes, and period details of the physical object. The lack of this idiosyncratic material makes the anthology more of a companion to the digital archives than a work that stands on its own. In addition, the editors did not include a number of key articles that would have supported different facets of the Souffles legend, such as contributions by the Black Panthers, the Angolan poet and political leader Mário de Andrade, or the mysterious Marxist historian “Mahmoud Hussein,” which was actually a pen name for Bahgat Elnadi and Adel Rifaat, two men who wrote as a team in Cairo, where they were arrested in 1966 and exiled from Egypt. Also absent is a compelling explanation by the editors of Mohamed Chebaa’s notion that an artwork could be a political position, complete in itself (this idea may have been clear in its day but is no longer obvious or even comprehensible without being unpacked and exemplified), as well as the notorious editorial on the Western Sahara, which ran in the final issue of Anfas and, when published in Arabic, probably set the fall of the entire enterprise in motion.

The anthology includes a number of illuminating texts on the importance of communal pluralism, not only Arab and Berber but also Jewish and Sufi. Serfaty, for example, is represented here not by his essays on labor strikes but rather through an engaging piece on Arab-Judeo culture in relation to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Written in 1969, Serfaty’s text insists that Moroccan Jews are central to the culture rather than a minority community long-suffering and repressed. Today, reading his assertion that Jews throughout the Arab world “will gain consciousness of their solidarity with the Arab revolution and will help to shatter the last historical attempt to lock Jews up in a ghetto—and what a ghetto . . . of global proportions” is like hearing a garbled missive from a distant planet. It proves a sad measure of how much North Africa and the Middle East have lost—and continue to lose—in terms of their once-vibrant multiplicity of voices and political positions.

In their introduction to the anthology’s final section, Harrison and Villa-Ignacio note that an editorial on the complacency of Arab regimes vis-à-vis Palestine, from 1971, “might have been written at the dawn of the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings [in the winter of 2010–11], were it not for a Marxist-Leninist and pan-Arab lexicon that feels dated today.” That may be true, except that the editorial in question is one of the rare uninspired selections in the book, the kind of rhetoric it uses still dismally common in newspaper editorials across the region today.

In her poem, “Jebu,” Adnan writes, amid atrocities all around, that “creative disorder / is our divine stubbornness . . . . Arabs are but a mirage which persists . . . I know / the total moon / the slow-motion sadness” of exile. In 1995, a decade into his own exile, Laâbi returned home and wrote, in “The Spleen of Casablanca,” a few lines that today seem both reflective of Souffles and prophetic: “I am trying to live / The task is arduous / What meaning should I give to this journey / What other language / shall I have to learn … Vertigo sets in / Confusion thrusts its waves . . . Creation hesitates . . . Who can / guess what comes next?” Since 2011, Laâbi has been both supportive and critical of Morocco’s anemic entry into the Arab Spring, the February 20 Movement, which, in his eyes, failed to turn demonstrations into real political propositions. And perhaps that is the lasting contribution of Souffles to the Arab world’s political, intellectual, and artistic discourse. The magazine’s contributors made such propositions all the time. They believed them to be real and possible and suffered mightily as a result. They insisted on the importance of creative sparks, bombastic ideas, and imaginative proposals for new cultures, new worlds, and new ways of living. They pursued them briefly but intensely. And then their project fractured and fell apart. Laâbi rightly mourns this. As should we all.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer and critic based in Beirut.