“If Elvis Presley is / King,” Amiri Baraka’s “In the Funk World” asked, “Who is James Brown, / God?” This, as far as black people throughout the world are concerned, is not a question but an assertion. “You want to say Elvis was King? Feel free,” we might say. “But he never ruled us!”

True, Elvis’s come-hither swagger may have compelled the American mainstream to deal with its complex transactions between classes, cultures, and races (along with parts of its own collective unconscious, as Greil Marcus reckoned in his essential 1975 rock ’n’ roll panorama, Mystery Train). But James Brown had just as explosive and resounding an impact on how black people viewed themselves—and, over time, how the rest of the nation viewed them—as any of the King’s recordings or performances did on postwar white America. A live Elvis appearance, especially in his mid-’50s incarnation, could set off near-riots among fans. But James Brown—and only James Brown—could keep rioting from happening in Boston after Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968.

Elvis has been dead for almost forty years, and yet folks (fewer than there used to be, perhaps) still think they’ve seen him in the express line at the nearest Piggly Wiggly or boarding the next westbound flight out of O’Hare. Meanwhile, when people listen to hip-hop and contemporary R&B, they know they sometimes hear the ghost of James Brown filtering through the tracks—guitar licks, drum rolls, and raspy, high-pitched screams lifted from his original records. Even so, you don’t need any sampled reminder to size up Brown’s vast influence on generations of rappers and rockers before and after he died on Christmas Day in 2006 at the age of seventy-three; his legacy continues to reverberate.

Such an outsize, galvanic presence in American life deserves deep, sustained examination, and from not just one angle but many. R. J. Smith’s The One (2012)is as thorough and shrewd a narrative of Brown’s life as we can expect to get so far. But James McBride’s new Kill ’Em and Leave makes a wary, focused, and altogether inventive broken-field run at the Godfather of Soul’s legacy, mostly through interviews with Brown’s friends, bandmates, colleagues, and financial advisers. The portrait that emerges through their words and McBride’s own trenchant, melancholy observations is of a “mass of contradictions . . . a man with miles of scorched earth behind him. He’d spent most of his entertainment life preaching the gospel of education and hard work, and now he was seen as a kind of clown.”

That sounds harsh, but it isn’t where Kill ’Em and Leave lands for good. The whole story of Brown and his world is too complex and enigmatic for any tidy assessment to prevail. McBride’s evaluation of Brown begins where everybody else’s does, but McBride speaks with the additional authority of a professional saxophonist: “He revolutionized American music: he was the very first to fuse jazz into popular funk; the very first to record a ‘live’ album that became a number-one record. His influence created several categories of music. . . . His band was revolutionary—it was made up of outstanding players and vocalists, among the best in popular music this nation has ever produced.”

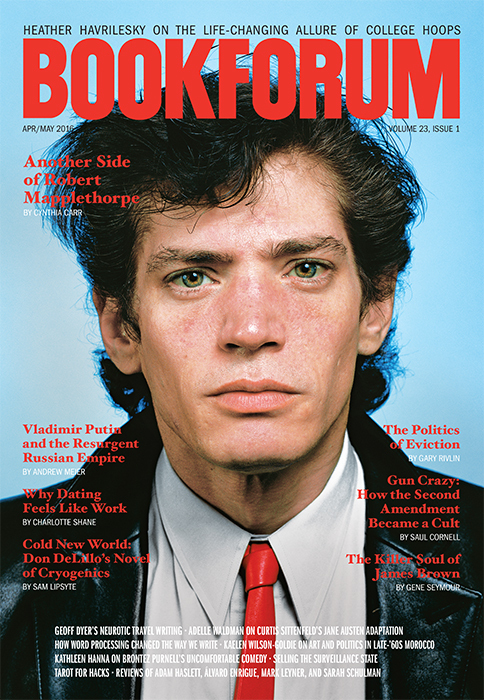

As with most considerations of the Godfather, this eminently justified case for Brown as genre-bending pioneer opens out onto a central contradiction—namely, Brown’s persistent struggle to win wider cultural renown: “James Brown never once made the cover of Rolling Stone magazine during his lifetime. To the music world, he was an odd appendage, a kind of freak, a large rock in the road that you couldn’t get around . . . a black category. He was a super talent. A great dancer. A real show. A laugher. A drug addict, a troublemaker, all hair and teeth. A guy who couldn’t stay out of trouble. The man simply defied description.”

The book begins with McBride’s childhood visit to Brown’s mansion in St. Albans, Queens, but the author wisely confines most of his mosaic to the American South. As McBride writes, “You cannot understand Brown without understanding that the land that produced him is a land of masks.” A musician knows his way around variations, but McBride also knows his way around masks: His breakout book, the 1996 best-selling memoir The Color of Water, focused on his mother, a white Polish Jew who concealed her ethnicity beneath an African American racial identity; and his most recent novel, the award-winning 2013 picaresque romp The Good Lord Bird, concerns a ten-year-old male slave from 1850s Kansas who is mistaken for a girl by the abolitionist rebel John Brown and becomes a kind of wandering muse for him on a far-flung tour of antebellum America before Brown’s date with destiny at Harper’s Ferry.

This more recent, but no less mercurial, Mr. Brown was, among many other things, a cagey, elusive trickster-god who was careful about how much he told even those closest to him about his life story—which has created another layer of difficulty for enterprising biographers. This was very much by design, as Brown told his most notorious protégé, Al Sharpton: “Don’t let folks get too familiar, Rev. Don’t stay in one place too long. Come important and leave important.” Such rough-hewn aphorisms about performance and image (including the one that gives the book its title) were for insiders like Sharpton. For youngsters in the audience, Brown stuck to the catechism of black self-help, echoing the gospel of success preached by Booker T. Washington: Stay in school and away from drugs. Their parents and the rest of the black community got much the same counsel, only right-sized for adults: Become more economically self-sufficient. This thorough rejection of welfare-as-we-once-knew-it obviously didn’t stick with Sharpton, but it did crop up in a number of signature Brown tunes, such as his 1969 hit “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door, I’ll Get It Myself).” Brown’s canny blend of laissez-faire orthodoxy and body-quaking funk was a key reason that Soul Brother Number One was a welcome, if unlikely-looking, guest at Richard Nixon’s White House. (McBride notes, however, that Brown met the man he supported in 1972 “with his trusty .38 in his coat pocket.”)

But duck: Here comes another contradiction. For all of his earnest bootstrap-lifting motivational talk, Brown was a “terrible businessman” whose ventures, including a pair of radio stations, a restaurant, and a nightclub, all went bust. Charles Bobbit, Brown’s personal manager, tells McBride that Brown knew how bad he was at managing money. “He said he was about sixty percent entertainer and forty percent business.” The financial misadventures continue beyond the grave: A considerable portion of Kill ’Em and Leave is devoted to the dismal fate of a $100 million trust fund designated by Brown to provide education to poor white and black children in Georgia and South Carolina after his passing. Nine years later, McBride writes, “not a dime of Brown’s money would go to educate a single impoverished child in either state.” Why? “The short answer is greed. The long answer is boring, which is how lawyers like it.”

The musician in McBride is savvy when it comes to assessing Brown’s work. He points out, for instance, that the theme of “Cold Sweat,” as conceived by longtime musical director Pee Wee Ellis, owes everything to Miles Davis’s “So What.” He is also a tender and solicitous listener, preserving the tone and pattern of testimonies from Brown’s inner circle as if he were protecting yellowed news clippings of family wedding announcements. There are all the familiar Brown consiglieri—Sharpton, Bobbit, and Ellis (who says at the outset that he’d rather talk about anything other than Brown, leaving the reasons for his reticence hidden from McBride’s queries). But McBride is just as considerate in his encounters with lesser-known figures. There’s Nafloyd Scott, the last surviving member of Brown’s original Famous Flames, who died blind and broke at the age of eighty, shortly after McBride met with him. There’s David Cannon, a white Republican lawyer from South Carolina who endured personal grief—and some jail time—for trying to do the right thing with Brown’s last will and testament. And there’s lifelong friend Leon Austin and his wife, known as “Miss Emma,” who, as with most of the others cited here, withstood all Brown’s volcanic tirades, jolting mood swings, and self-destructive tendencies.

In the end, Miss Emma delivers perhaps the closest thing in Kill ’Em and Leave to a unified theory of Brown’s life and career. It’s a panegyric that’s perfectly fitting—and absolutely heartbreaking: “He carried so many people. . . . And so few people wanted to carry him. He always moved with the best intentions. And when it didn’t work, it hurt him. He hid that from people. Because people used him. And after a while, he didn’t know who to trust.”

All right, then: not “God,” exactly, but someone who certainly played one on the stage and on the radio, whose ways were a mystery to everybody, including (and maybe especially) himself.

Gene Seymour’s most recent article for Bookforum was about the gothic writer Charles Beaumont. He has written about film and jazz and is working on a collection of essays.