I don’t care how much your parents fucking loved you—you’ve got problems. Me, I was abused by an alcoholic father, molested by a neighbor, kidnapped and raped at fifteen, so my PTSD is like a fungus with more PTSD mushrooming on top of it. I go to therapy to tell all these crazy stories over and over till they become just stories. Like a house that grows smaller and smaller out the back window of a car. Luckily, I’m a musician, so I can also write songs about this stuff. I can’t tell you how powerful it is to write a “Fuck You” song about my dad and get paid for it. To mix what happened to me with things I’ve read, dreams, conversations, and to come out the other side with something I can sell on iTunes: more money for therapy!

I do get tired, though, of people assuming my work is only therapeutic, or that the words just spewed out of me. There’s an art to turning personal tragedies and brushes with oppression into your own, sometimes funny narratives. It’s like pulling a sliver out of your foot and fashioning it into a tiny little sword. One of my favorite writers who also works like this is Brontez Purnell, whom I heard read recently at the Bureau of General Services—Queer Division, a Greenwich Village bookstore in an LGBT community center. Purnell doesn’t fit into an established literary canon, but he cites as influences everyone from Mike Albo, author of the brilliant novel Hornito, to Alvin Orloff (a member of San Francisco queer art collective the Popstitutes), to the writer and activist Michelle Tea, all of whom could be accused of spewing by someone who wasn’t paying enough attention.

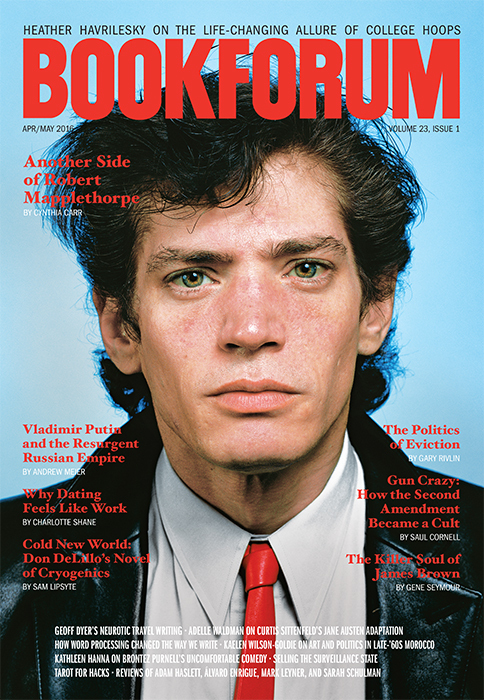

Purnell’s new book, Johnny, Would You Love Me If My Dick Were Bigger? (Rudos and Rubes Publishing, $12), a “fictionalized memoir” told in fragments, is a vivid portrait of “Brontez,” a pissed-off, judgmental, extremely lovable guy who does not give a fuck—and is funny as hell. It’s an ingenious kind of comedy: Purnell often starts with a self-deprecating joke, cutting himself with the knife of humor before using it to slice a path forward a few sentences later. He also has a strong sense of the absurd. One lover claims to be so well-endowed that a night with him will turn Brontez into a woman. For the rest of the paragraph, Brontez is one, experiencing all the “stress” of womanhood: “What if I got pregnant? And worse still, what if I get pregnant by a poor person? Ew! Just like my mom!”

His strongest suit is timing: Just at the moment when you start to wonder where he’s going with a story, he gives it a bizarre, unexpected resolution—and adds a punch line. “It was of course a mistake to date another writer,” Brontez says of a boyfriend who’s always getting his stories, all of which are “about the Incredible Adventures of Two Boring Ass White Dudes in Love,” published in the “New Best Gay Erotic Fiction Volume What the Fuck Ever.” “We differed and disagreed stylistically,” Brontez says, hating the “plucky wide-eyedness” of the other guy’s work: “why couldn’t one of the precious boys be a murderer and a junkie or have an eating disorder?” A paragraph later, Brontez pours lighter fluid on the boyfriend’s silver laptop and it goes up in flames. “He never talked to me ever again,” he writes, “and he could never really return the favor: My stories were already on fire.”

Purnell’s book feels very immediate, but nothing is there by accident: There are poems, numbered lists, “reviews” of bad parties and blackouts, even a natal chart and a treatment for a dance show, all echoing and building on each other. One of his cleverest moves is to include exercises for a (fictional) writing class. That allows Purnell’s protagonist, a gay, black man, to flip the dynamic and observe his more privileged classmates for the strange, exotic creatures they really are. “I was beginning to bum out my . . . classmates with my AIDS jokes and apocalyptic bullshit,” he writes, but then another student gets a standing ovation from the class for bravely sharing that “I know someone who died of AIDS.” Purnell almost doesn’t need to comment—he just repeats that telling word: “Someone.”

What Purnell can do with humor is extremely complex, forcing you, as a reader, to constantly shift positions, identifying with Brontez’s adventures one moment, recoiling the next, laughing even as you realize that the joke could be on you. Like me, the Brontez character has a therapist—one who gives him a pretty hard time. Therapy is another literary device for Purnell. Instructing Brontez to write a story about his life, the therapist says: “Pay close attention to the actions of the boy in that story . . . . Can you live with the boy in that story?” At one point, he tells him to go to IKEA with an imaginary boyfriend, just so he can see what it might feel like to stop all the anonymous sex and settle down. Brontez ends up standing outside the store with seven hundred dollars’ worth of stuff he can’t afford, wondering when his “imaginary car” is going to show up and take him to the “imaginary apartment” that could actually fit his very real purchases. It’s a joke at his own expense, but it’s also one about how much class has to do with fantasies of love and the good life.

Purnell’s is the kind of book you’re supposed to hide behind Eat, Pray, Love when your relatives come over. He tells the stories most people try to strangle with their bare hands under the table at family dinners. And he tells them as if it were completely normal to, say, crack several jokes in a row about being molested. For Purnell, it is normal to crack those jokes. What’s abnormal is bullshit like Sante Fe wallpaper borders and the TV show Frasier. In my alternate universe, Purnell would be required reading in high school. I can hear the teacher now. Class, what does Purnell mean in the following passage? “I was getting retardedly baked with a bunch of lady men at the park. A very boastful friend was feeling high and mighty ’cause he was the only practicing fist fucker amongst us. ‘IT’S THE MOST POWERFUL CONNECTION YOU WILL EVER FEEL WITH ANYONE. EVER’ he declared, as if sharing a favorite TV show or flavor of ice cream didn’t count.” Then the teacher would ask, Now class, is fist-fucking a metaphor for something else here?

It is and it isn’t. In Johnny, sex is everywhere. As a longing to be truly seen, as entertainment, as distraction, as self-punishment. The last thing this book attempts to do is make straight people like or (barf) “tolerate” gayness. Purnell knows that promiscuity is a big part of a stereotype other people use to stigmatize gay men, but he doesn’t let it prevent him from being promiscuous when he wants to be. He also knows, though, that real freedom includes the freedom to not be “empowered,” to not be a role model—Brontez makes crazy, stupid, self-destructive decisions, regrets them, makes them again, and then laughs at himself and at anyone who tries to judge him for it. Inhabiting the stereotype is sometimes part of being complex and human; it also, it turns out, gives him insight into the hypocrisies of everyone around him. A change comes over the counselor at the clinic where Brontez (the character) learns that he’s HIV positive, for instance, as soon as he lies and tells her he must have caught it from his long-term boyfriend, who cheated. Suddenly, she’s sympathetic: “Oh honey! Here’s some tissue! The world is so unfair! That monster!” Brontez wonders, “How come there’s no sympathy for sluts? Like none? What if I had told the truth? ‘Oh, I just wanted to be liked.’ ” As he’s leaving, the counselor offers him some condoms and lubricant. “I took the lube,” he writes.

“I meet so many other queer black boys who write who feel like they have to be the next James Baldwin,” Purnell said at the Bureau Division event. “Meanwhile, a fuckin’ white boy can write about fuckin’ a dog or jumpin’ out of windows. He ain’t got the weight of the entire fuckin’ race on his shoulders. I always tell the other black boys, ‘Do you. That’s what people want and people need to hear our stories now.’” That’s exactly what he does. He knows his work is better when he’s not trying to be likable or write the book others may expect from him. Harsh honesty prevails, whether the story he’s telling is about Brontez having sex for three hours with a “bug chaser” (someone who seeks out HIV-positive partners to try to catch the virus), or getting kicked out of a club for throwing a white woman’s “tacky” patent-leather clutch across the room after she annoyed him, or skipping out on a Barebackers Anonymous meeting for a tryst with another member of the group.

To make work like this, you have to be kind of a furious optimist. That’s what Purnell seems like to me, always thinking the perfect thing is right around the corner, then finding that around that corner there are only more bad jobs and getting drunk, more married guys or just super-gross asshole dudes—and plowing all of that back into his stories. Hopeful and defiant, honest and artful, he always juxtaposes the funniest stuff with the most tragic, heightening both, refusing to choose: “The trick of the balance for me,” he writes, “has always been to demonstrate that alongside the laughter, I’m still dead fucking serious.”

Kathleen Hanna is the lead singer of The Julie Ruin. The Punk Singer, a documentary about her, was released in 2013.