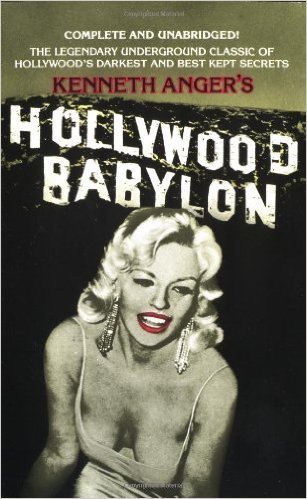

KENNETH ANGER—UNDERGROUND artist, queer-film pioneer, outrageous occultist, and dated purveyor of misogynist, racist, and homophobic snark—wrote several versions of this vulgar compendium of Tinseltown tragedy (Anger’s style tends toward gleeful, relentless alliteration) before the definitive version was published in 1975. By the time I discovered it in the 1980s, it was a trash classic, up there with Pink Flamingos, Russ Meyer films, and Valley of the Dolls. But Hollywood Babylon wasn’t merely bad taste; it was bad taste with a death obsession (from the suicide of failed starlet and “man-addict” Lupe Vélez, to the studio-forced sanitarium death of Wally Reid, to the ultimate “big-wig” cover-up: a movie producer shot to death on William Randolph Hearst’s yacht). Offensive morbidity was a rite of passage in Los Angeles: Kids would get high at the gravestones of stars, drive up to the corner where Montgomery Clift had his accident, or park on Cielo Drive, where the Manson Family committed their horrific home invasion.

Laughing at lurid cultural artifacts felt transgressive, a cheap and easy form of subversion. But mostly it felt like bracing sophistication after being raised on the processed celebrity culture of the ’80s, which ranged from the fakery of Battle of the Network Stars to the fakery of supermarket tabloids. It was all so humdrum and devoid of style. Hollywood Babylon was fake, tacky, and offensive, but it was never dull: It rescued from obscurity the truly decadent and glamorous old-time stars of the silent era, like the stunningly beautiful “heroin heroine” Barbara La Marr. It also revisited the scandals—such as Fatty Arbuckle grotesquely raping a starlet and leaving her to die—that gave rise to the Hays Code, named for William Hays, the corrupt Republican operative who would protect American cinema audiences from sex, drugs, and any kind of moral ambiguity. Anger has a lot of contempt for the suffering of stars, but his deeper disdain is aimed at Hays and the studio moneymen who hired him. The Code, according to Anger, pushed everyone into the closet and made everyone into a hypocrite.

The reader’s pleasure is partly born of discovering the truth behind the hype and false propriety of the prudish studio machine. Still, one can’t avoid the irony in Anger’s (and the reader’s) tabloid voyeurism. Another part of the pleasure is that we get to feel righteous even as we stare at the pain of others. Anger plays into the complicated desire-resentment we feel for the famous. We may not be beautiful actors, but look how awful their lives really were. We are better, we know better, just look at their messy corpses—as if any one of us would be any less ridiculous if someone photographed us at our worst moments. Reading about (and ogling) the ruined, corrupted, and exploited stars (and aspirant stars) while imagining we are not part of it, somehow, is just another form of hypocrisy. One can argue that Anger knows this, and that his ultimate disdain is for you, his reader.

Dana Spiotta’s novel Innocents and Others was published by Scribner in March.