The hottest writer in America right now has been dead for thirty years, proving how so many people for so very long got James Baldwin so very wrong.

When Baldwin died in 1987, at sixty-three, his importance as a literary voice for the civil-rights movement as well as his not-as-heralded-but-just-as-significant stature as a celebrated black and openly gay novelist was so widely acknowledged as to be almost taken for granted. Yet there were many book-chat pundits, especially in the years leading to Baldwin’s passing, who were ready to write him off as Yesterday’s News, someone whose artistic and political capital had been all but spent in the Morning-in-America 1980s of conservative triumphalism.

Guess again, geniuses. As we move deeper into the twenty-first century, James Baldwin is unavoidable in ways that mid- to late-twentieth-century literary contemporaries such as Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer are, simply put, not. His influence can be found, directly and indirectly, in the poetry, plays, pop music, and prose of a younger generation of African American artists and writers, notably Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose blockbuster Between the World and Me (2015)borrowed its framing device from Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (1963): Both books examine America’s racial divide in the form of a letter to a younger relative (Baldwin addresses his nephew, Coates his own son). The Library of America edition of Baldwin’s Collected Essays, edited by Toni Morrison, has in the years since its release in 1998 become an urtext for the Black Lives Matter movement and its sympathizers. Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, an Oscar-nominated montage of Baldwin’s interviews and speeches molded to engage the present-day Sturm und Drangof interracial affairs, grossed more than $7 million (and counting) in the nation’s theaters, and a book based on Peck’s film, which quotes liberally from one of Baldwin’s unfinished novels, has become an Amazon best seller.

Most of the elements in the Baldwin resurgence are tabulated and examined in William J. Maxwell’s introduction to James Baldwin: The FBI File. He considers the seeming paradox of a writer with Baldwin’s “long and gracefully overstuffed sentences” being embraced so passionately in the Twitter era, observing that “the blend of political prophesy and theatrical self-exposure in nearly all of his essays, regardless of their topic, indeed anticipates the very twenty-first-century job description of the freedom fighter/social media star.” Maxwell nails down his case by quoting a “firmly vernacular” tweet from a Brooklyn BLM supporter awed by the Jamesian sprawl and pitch of Baldwin’s prose: “Sentences be a page long and still grammatically correct. That boy ice cold.”

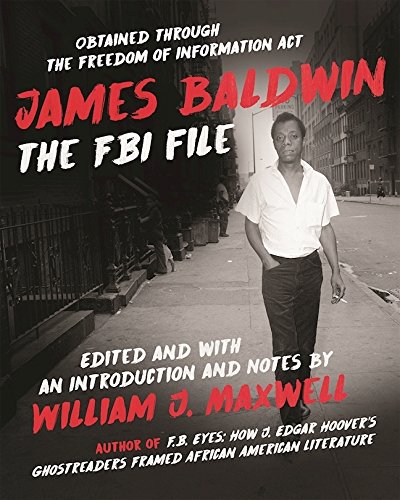

It’s too bad that such stirring observations serve as prelude to the petty-minded buffoonery exemplified by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s decade-plus surveillance of Baldwin. It was in 2015’s F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature that Maxwell revealed that Baldwin’s FBI file is 1,884 pages long, the largest of any black American writer. It was compiled when the organization, under J. Edgar Hoover’s stewardship, zealously pursued evidence of government subversion by black artists—and (of course) found nothing whatsoever. James Baldwin: The FBI File, Maxwell’s sequel-of-sorts to F.B. Eyes, does not—thank the gods!—present the complete file, though if you wish, you can see the whole thing online. Why you’d want to, given the repetitive nature of what’s displayed in this by turns amusing and enraging cornucopia of declassified (if still redacted) office memos, transcripts, press clippings, and field reports, is a mystery; but perhaps not as big a mystery as why the Bureau dug so hard and for so long into Baldwin’s life.

Maxwell believes a clue lies in a note scrawled by Hoover himself on a July 17, 1964, memorandum asking, “Isn’t Baldwin a well-known pervert?” Perhaps the director looked askance at famous people who did not conceal their homosexuality, even though his own live-in relationship with his associate director Clyde Tolson, which Maxwell calls “the worst-hidden gay marriage in official Washington,” was “visible just beyond the margins.” An interoffice response came three days later from M. A. Jones, an officer with the bureau’s Crime Records Division (“the FBI’s public relations department in all but name”), who cautioned his bosses: “It is not a matter of official record that [Baldwin] is a pervert; however, the theme of homosexuality has figured prominently in two of his three published novels. Baldwin has stated that it is also ‘implicit’ in his first novel.” (The novels referred to are 1956’s Giovanni’s Room and 1962’s Another Country, and 1953’s Go Tell It on the Mountain.)

Well, at least somebody around the office was actually acknowledging, if not reading, the books. Indeed, as F.B. Eyes attests, a handful of FBI agents flashed some impressive lit-crit chops when analyzing the work of their black “subjects.” There was the unnamed Philadelphia G-man, for instance, who was assigned in 1959 to look for evidence of communist influence in a preview performance of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun and submitted what Maxwell describes as “a perceptive and even-tempered four-page review.” Hansberry’s FBI file nonetheless weighed in at 1,020 pages.

But the “intelligence” gathered in the Baldwin file makes a mythic dimwit like Maxwell Smart look more like George Smiley. As late in the game as 1968, the Bureau officially listed Baldwin as an “Independent Black Nationalist Extremist,” even though anybody paying attention at the time would have known that Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver had published an essay in his acclaimed and then-influential collection Soul on Ice virulently attacking Baldwin for, among other things, expressing “the most shameful, fanatical, fawning, sycophantic love of the whites that one can find in the writings of any black American writer of note in our time.” Baldwin, for his part, wrote in his 1972 book-length essay No Name in the Street that while he was “impressed” with Cleaver, he believed the latter had “used my public reputation against me both naively and unjustly.” It was an assessment that just as easily applied to the nature of the Bureau’s obsession with him. Here and elsewhere in Baldwin’s transactions with the FBI, the irony is so thick you could eat it with a fork.

You wonder, for instance, what exactly the FBI was looking for at a December 1963 fundraising dinner of the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee in New York where Baldwin and what the Bureau’s report labeled a “young beatnik type entertainer” named “Bobby Dillon” spoke. The agents in the audience reported that Baldwin was “the author of a book” and “spoke of the prejudice against Negroes in the civil rights movement.” But it was the speech by “Dillon” (aka Bob Dylan) that ended up in pop history, primarily due to the future Nobel laureate’s reflections on being able to “understand” Lee Harvey Oswald, who’d murdered President John F. Kennedy less than a month before. His talk, the agents’ report stated, “was not well received.”

A far more infuriating example of the Bureau’s cluelessness took place earlier that same year when Baldwin appeared in Selma, Alabama, where civil-rights leaders were beginning their epoch-making voter-registration drive. Agents were more intent on taking pictures of Baldwin and James Forman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) than preventing the brutality visited on would-be voters by Sheriff Jim Clark and local police. Along with these egregious displays of indifference there were more comedic red herrings, such as a mildly hysterical report in 1967 by an agent claiming Baldwin had married his sister Paula. There’s also a postcard in the file from an unnamed source blaming Baldwin (and “Negroid Jews resembling Castro”) for the July 1964 Harlem riots, along with a memo revealing the Bureau’s peculiar fixation on Baldwin’s use of the endearment “baby” in a phone conversation with a former aide to Martin Luther King Jr. Your tax dollars at work.

Still, with hindsight, it’s possible to view James Baldwin: The FBI File as a mixed-media, nonfiction satire of officially sanctioned racist paranoia run amok. One could also praise Maxwell for having sculpted from this mound of random documents some ramshackle version of the Hoover-bashing novel Baldwin himself intended to write. (The working title of that book, The Blood Counters, came from “the negroes’ nickname for the FBI.”) There’s evidence throughout the book that Baldwin gave back to the FBI as good as he got, baiting the easily baitable Hoover by declaring in a 1963 television interview that the director “was part of the problem in the civil rights movement.”

Sometimes, in getting James Baldwin wrong, the Feds somehow (and unknowingly) managed to find out something about their “subject” that turns out to be illuminating. In December 1969, still almost five years before the Baldwin file was officially closed, a Bureau report describes (as always, with derision) his “method of working,” citing how “he writes continuously for 24 hours without food and drink. . . . Afterwards, he lies down and sleeps” a “sound sleep for 48 hours.” The report continues: “If you are able to awaken him, how fortunate you are.” Golly. Let’s definitely keep an eye on that weirdo!

Consider also the contrasting points of view concerning Baldwin’s fateful visit, in the summer of 1961, to the Chicago home of Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, who’d invited the author to dinner and praised Baldwin for his “televised attacks on white hypocrisy and racist violence.” You could use the full government report on that meeting as hypertext to The Fire Next Time’s far richer and more nuanced depiction. But one wonders if the Bureau ever bothered to compare its notes with Baldwin’s own account when it ran originally in the New Yorker the following year. If they had, they would have encountered Baldwin’s assessment of the Nation’s black-nationalist goals in maxims that he followed all his life, however malignly circumstances had turned against his people: “The glorification of one race and the consequent debasement of another—or others—always has been and always will be a recipe for murder. There is no way around this. . . . Whoever debases others is debasing himself.”

Despite thoughts such as these, guardians of the republic thought James Baldwin was a danger to society. Let that sink in during the next several minutes you sacrifice to the surface-skimming content of present-day cable news.

Gene Seymour has published articles recently in Chamber Music magazine and the New York Times.