I’ve heard it argued—and I agree—that fiction that builds a universe whose rules depart from our own allows for the contemplation of ethical dilemmas that cannot be addressed in or by the world as we know it. This kind of fiction—what my toddler might call “same but different”—tends to disrupt our go-to feelings. In an alternate universe, you are moved to relitigate the basics because you cannot take anything for granted. The sun is black; the moon is pink; everything we know needs to be reevaluated—the facts of our lives and, by extension, the principles we hold dear. Similarly, fiction that distends what is real—that trucks in extremes—often allows us to see more clearly what’s wrong with the way things are now. In both cases we’re given space to reflect and reconsider.

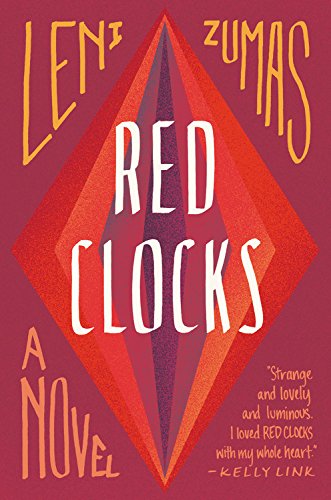

Leni Zumas’s spry new novel, Red Clocks, does a nice job both of denaturing the world and of riffing on extreme versions of it. Though it’s worth noting that had this novel been published even two years ago, it would have seemed considerably more extreme than it actually is. Easier, too, to dismiss. Alternate universes in fiction raise ethical dilemmas that can still feel hypothetical—that are hypothetical until the gap between what is real and what has been imagined begins to close precipitously. In Red Clocks we’ve got a misogynist dystopia that’s about one vote away from becoming our day-to-day. Here, Roe v. Wade has been overturned. In its moral stead: the Personhood Amendment, which grants rights to a fertilized egg. Thus IVF is outlawed, abortion is criminalized, and anyone attempting either can be charged with manslaughter, murder, or, who knows, abduction of a minor. In an extra affront to progress, the Every Child Needs Two Law has also been passed, which mandates that only two-parent families can adopt. Play all this out for a single woman in her forties and you’ve got the first of the four women who dominate the novel. Zumas showcases their experience of femaleness and, in so doing, asks us to rethink what it really means to be female in a world that’s written almost exclusively by men and, in particular, by men who know nothing—and care nothing—for women’s rights. If this sounds all too familiar, your dread reading this novel will be palpable.

The single woman’s name is Ro, but she is called “The Biographer.” She’s writing about a fictionalized nineteenth-century explorer of the Arctic who is subjected to chauvinism from the start of her life to its end. The novel’s main narrative is spliced with excerpts from the biographer’s unfinished manuscript, which are compelling and sad and grist for all manner of analogies between the explorer’s plight and what’s happening not just to the biographer but to women the world round. We are marginalized, plagiarized, dismissed, accused.

While the biographer chronicles one female life—“They did not believe me that vitamin A occurs at toxic levels in polar-bear livers. They are saying I cursed the stew”—she is also chronicling her own. She watches herself inhabit the persona of a single woman who desperately wants a child even as she questions whether she’s wearing that mantle of desire for show or if she’s wearing it at all. Of course. It’s often hard to know what you really want when millennia of culture have conditioned you to want, above all, one thing, which is to parent. Even so, the biographer’s doubt is equally consequent on the supremely slim chances of her being able to conceive. It’s always easier to rethink what we want when we’re not getting it. So, it’s complicated.

Enter “The Wife,” who’s less complicated, more stock. She’s in a marriage she doesn’t like. Her husband is self-absorbed, inattentive, clueless. They have two kids. They are 50 percent of the marriages in America today, if not more. The wife is beleaguered and oppressed by the onus of having to be a wife and a mom and by all the mechanics of the job:

Spray table.

Wipe down table.

Rinse cups and bowls.

Put cups and bowls in dishwasher.

Soak quinoa in bowl of water.

Rinse and chop red bell peppers.

And so on. Distill our lives into their rote and probably most of us won’t like what we see either. Some of us might even search for the courage to try something else. The wife is an archetype (which is by design; she is called “The Wife,” after all), though she is still capable of delivering fresh observations that render womanhood with droll accuracy: “What joy to walk naked after a shower and hear your labia clap. To rise from the toilet and hear your labia clap.” The novel is often at its best when being sharp and funny in this way.

There are, too, “The Daughter” and “The Mender,” each of whom also has to reconcile with the role into which she’s been cast, though the daughter might have been better called “The Teenager.” She’s young, she’s pregnant, and in this particular environment she has few options for ending her pregnancy: “term” houses or a flight to Canada, though thanks to the “Pink Wall,” Canada is none too friendly to girls in extremis. Do we really need to go down this rabbit hole to reassess whether outlawing abortion is such a bad idea? Surely now, perhaps more than ever, we do. The daughter is suitably terrified, and her misery the endgame of a patriarchy’s rise to elected power. No one—least of all a young girl—should have so few options for moving forward with a life of her own reckoning. I have always felt this way, but it’s nice when a novel forces me to revisit the foundation of my values. It’s a little bit like rereading your favorite books every decade or so. I’m the same, but different, which allows me to question what, if anything, has changed in these books for me.

Meantime, there is “The Mender,” perhaps the most interesting of the four leads, though she, too, has been cut from a cloth women have been made to wear for centuries. She’s a healer, a homeopath, a cook, a witch. If our polar explorer has “cursed the stew,” the mender’s making stews and poultices and tinctures that threaten Western medicine and, in a way, the maleness it represents. At some point the biographer visits the mender for help with her fertility. “But what if it works?” she wonders. “Thousands of years in the making, fine-tuned by women in the dark creases of history, helping each other.” In this sentiment is the essence of what we talk about when we talk about women through the ages—in the dark creases (I love that), secretly propping each other up, and, of course, keeping everyone alive. The mender, who is not a witch but who is rather odd, absconds from society because she wants to. Because what’s out there is so uninviting. It’s no surprise that so many of the women who haven’t made the choice to retreat seek her out with regularity. And yet there’s never a respite from misogyny or bias, no matter how reclusive you are. The mender is an easy target for a culture that likes to label women—bitch, witch, ball-breaker—and so it’s not long before she’s hauled out of her life and into the spotlight just for being who she is.

For all its polemics, Red Clocks is actually most notable for the brio of its prose—its excellent sense of timing and cadence. The novel moves at a clip. Often it’s downright jaunty. This has the benefit of ensuring that we never get stuck in any one place, though now and then reading the novel felt like being on a conveyor belt moving through a zoo. Sometimes you just want to stop and look at the animals. Especially if taking a moment means being able to contemplate more thoroughly the pathos of, say, the world conspiring to guarantee that everything you want will never happen. Still, this is a small complaint of a novel that, when it wants to, can slow down long enough to capture with depressing precision how so many problems women face just get passed down from one generation to the next regardless of how hard we try to arrest the legacy. “Am I fat?” asks the wife’s young daughter.

“No!”

Voice wobbly: “I weigh eight pounds more than Shell.”

“Oh sweetpea.” She kneels down on the kitchen floor, gathering Bex in her lap. “You’re exactly the right size for you. Who cares how much Shell weighs? You’re beautiful and perfect just the way you are.”

The wife fails, as a parent, on so many fronts.

“You’re my perfect darling gorgeous girl.”

Did your heart just sink? Mine did. Who needs a misogynist dystopia when things are already this hard? We need the dystopia to remind us that things really are as hard as they seem. And we need the dystopia to remind us that when we do nothing, hard things get harder. Time’s a-ticking, this novel seems to say. Wake up.

Fiona Maazel is the author of the novels A Little More Human (2017), Woke Up Lonely (2013; both Graywolf Press), and Last Last Chance (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008).