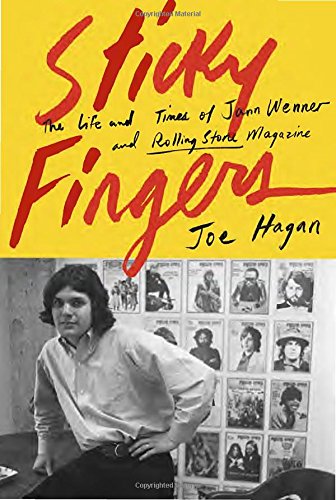

Sticky Fingers raises an overdue question: Is the era of devoting epic tomes to the exploits of mercurial pricks officially over? If so, Joe Hagan’s skilled filleting of Jann Wenner’s history as the publisher of Rolling Stone magazine is one hell of a coffin nail.

The book was born over lunch at an upstate New York eatery. Wenner, in his egotism, offered Hagan, then a journalist at New York magazine, unfettered access and deep cooperation (he asked to review only details of his sex life, which are nonetheless abundant), without requiring final approval, so sure was he that Hagan’s excavation would evince his greatness. As it turns out, Wenner is furious about Hagan’s final product. After reading a prepublication galley of Sticky Fingers, the New York Post reports, a furious Wenner kicked Hagan off the bill of a panel discussion they were supposed to co-headline. Wenner’s cocksure bargain didn’t go as he’d planned—instead of further enshrining the myth of “Mr. Rolling Stone,” Hagan rightsized his legacy entirely.

Hagan, quite clearly, is without an agenda, and Sticky Fingers is not posited as a takedown of “Mr. Rolling Stone.” Still, the tenor of the accounting of Wenner’s life after 1967, the year he founded the magazine, is inevitably shaped largely by the fact that everyone who has ever loved or liked him seemingly loathed him in equal measure (the holdouts being Tom Wolfe, Wenner’s son Gus, possibly Bette Midler). Many offer remembrances from the seat of betrayal, often one that’s been steeped in acid resentment for decades.

Over the course of the book, Wenner’s life and actions conjure only modest empathy, save for the natural tenderness one feels for anyone who’s had a truly grievous childhood—Wenner’s dad ruled with the back of his hand, and his mother was a tragic narcissist. Cocaine-fueled petulance was apparently Wenner’s default setting through the 1970s and early ’80s, but from the jump his savvy and ambition drew remarkable talent in to Rolling Stone (Hunter S. Thompson’s sagacious presence gets special attention). That he would soon steamroll those same people becomes a foregone conclusion. Sticky Fingers opens with the sort of scene that becomes its defining feature: Jann Wenner sells someone out, transacting on a relationship for whatever gain could be exacted. We meet Wenner as he is poisoning his friendship with no less than John Lennon, betraying Lennon’s trust for a $40,000 book advance. This is grimglorious rock gossip, but who really wants to read about the exploits of a vain, power-mad scoundrel running/ruining a great thing while we are living that very sitch in 2017’s Technicolor real time?

Sticky Fingers may sell on the basis of its ample and sometimes ridiculous rock-world lore—Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney eagerly avail themselves for score-settling—but this is all incidental to the book’s grander purposes. Hagan’s most enviable feat is that he makes this harsh history readable not by portraying Wenner as a redeemable figure (there’s no goblin with a heart of gold here), but instead by centralizing the very ambitious women who made Wenner’s path-blazing possible. Wenner’s ballast throughout the founding and rise of Rolling Stone—and his absolute recklessness with it all—is his ex-wife Jane. (I found myself willing to read about Jann’s tawdry tantrums just for more Jane. Decades on, she is still the real draw.)

The Faustian bargain of their marriage in 1968 reveals how far the sexual revolution still had to go, and how, even amid the supposed counterculture, mainstream American mores were still in effect. Despite the Wenners being Haight-headquartered avatars of the rock ’n’ roll youth culture demolishing the staid median, they were each other’s vehicles for realization and professional success. Jane’s exacting social graces and proximity gave Wenner’s queerness cover; Jane got to experience personal freedom and actively access her ambition, although it was often cloaked in Jann’s achievement. Jane was on the Rolling Stone masthead early on (as head of subscriptions), but was not properly credited for what she actually did; as Hagan documents, Jane was essential to the founding and survival of the magazine, mending crucial relationships Jann would destroy (including, until the ’90s, their own) and drawing talented contributors into the organization’s orbit and keeping them there. Jane was as luminous as Jann was coarse.

As the Majesty of Jane becomes the quiet through line of Rolling Stone’s first two decades, the question looms: When do we get a Jane Wenner book? When will we see the lives of rock’s founding women without having them lensed through the lives of the men around them? Early RS editor Harriet Fier’s experience merits its own book. And we need at least a biopic on the five female RS staffers who in the early ’70s regularly held secret meetings to console and support one another—a group of women who, as Hagan reveals, were the de facto editors of Rolling Stone, putting the magazine together while Joe Eszterhas was at the bar. Reading these passages, it’s hard not to wonder what music culture and cultural journalism would look like if any of the women at the foundation of Rolling Stone (Annie Leibovitz being the notable exception) had been given proper recognition (Renata Adler helped edit the landmark “Family” issue, uncredited). Another necessary lament: What would be different today if female artists had been regularly celebrated on Rolling Stone’s cover, rather than misunderstood and even smeared by powerful men in its review pages? The coolness and cunning of the women who lace through Wenner’s orbit (US Weekly’s Janice Min and early RS staffer Laurel Gonsalves merit mention) make them some of the most naturally fascinating characters in Sticky Fingers—which is saying something given that Hagan’s book includes such a surfeit of named-name trysts and celebrities engaged in sordid pharmacological exploits.

Wenner might justify some of his behavior by pointing out that his every waking moment had to be an act of opportunistic bravado in order to get Rolling Stone off the ground; the magazine was a big idea that had never before been brought into the mainstream. It was not just a new idea in publishing; it was a new prospect in American culture itself—a platform for the kids, the counterculture, and the unedited musings of an extremely high Pete Townshend. For the magazine’s first decade, trying to get corporate buy-in on the value of long-haired rock musicians and their teen true believers, as a consumer class, was a constant battle. The magazine’s survival was a by-product of the force of will of everyone listed on the masthead; most everyone was doing it for the love of music. Rolling Stone’s nascence was driven by its passion for dialogue with and documentation of youth culture. The sex, drugs, and access came later. Helping establish New Journalism was the magazine’s loftiest aim, and one it achieved absolutely, with watershed work from Hunter S. Thompson, Tom Wolfe, Grover Lewis, Lester Bangs, Howard Kohn, David Weir, and Joe Eszterhas.

Jann Wenner certainly started in the same earnest place, in love with the music and culture and their new possibilities—though what created a chasm between him and his staff was that he was also in it for the power, proximity to celebrity, and money. Speaking as someone who has tried once or twice to fuel a music magazine with sheer altruism, I can tell you that you need something a bit more opportunistic to sustain it. By any measure, Wenner’s unchecked capitalist self-interest “worked.” “He wanted to overthrow the establishment by becoming the establishment,” Hagan writes, calling him a “pioneer in the age of narcissism.”

Yet Wenner’s force of will helped create and bolster an industry. The influential talents Rolling Stone gave pages to are dozens deep, from Hunter S. Thompson to Matt Taibbi. Over time, Sticky Fingers reveals, Wenner became less a member of the Rolling Stone journalistic community and more its estranged, benevolent dictator. As the book evidences, for-profit music journalism was doomed (or damned) from the start; access and ad bucks were leveraged by labels from the beginning—at one point an RS New York bureau operated out of the office of a major record label for free.

Hagan’s book is both highbrow cultural digest—a curious journalistic trip through the past fifty years of the (largely white) halls of music-biz power—and, thanks to the debauched nature of rock ’n’ roll’s coagulants sex and drugs, a gloriously trashy read. Wenner’s bad side seats thousands, making for some grade-A gossip and catty digs. That said, the rock-cultural deep dive Hagan provides is also crucial and compelling. Even if you don’t have a long-standing interest in, say, Art Garfunkel grudges circa 1974 (some of us do!), or the fact that David Geffen, believing Wenner was in bed with the cassette industry, stopped purchasing ads, Hagan offers a good deal of insight into the ways that rock ’n’ roll’s legacy shaped—and in some cases warped—the American landscape.

In following Wenner from his days of rewarding his meager staff with drugs and watching early issues roll off the presses, into his ’90s private-jet-and-chill years, Sticky Fingers creates an epitaph for an industry rather than a shrine to a man who shaped it. The book beckons a new era, one hopes, of music history, one that’s less interested in gilding totems than in looking beyond them, to see what they obscure.

Jessica Hopper is the author of The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic (Featherproof, 2015).