Garry Winogrand died on March 19, 1984, at the age of fifty-six—too quickly and too soon. Just six weeks earlier he had been diagnosed with gallbladder cancer and gone to Tijuana seeking an alternative cure. Anyone would have left behind unfinished work, but this was Winogrand, who, with his Leica M4, made pictures as prolifically as a digital photographer, so we’re talking mountains. In the end, he left behind 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film and 6,500 rolls of developed negatives that were never printed. Today, the Garry Winogrand Archive at the Center for Creative Photography includes more than 20,000 fine and work prints, 30,000 contact sheets, 100,000 negatives, and 45,000 35-mm color slides, as well as a small group of Polaroid prints and motion-picture films.

How, then, to approach such a tremendous volume of work, and how to present it?

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, when mounting its major 2013 Winogrand exhibition, included nearly a hundred images from the previously unseen rolls. John Szarkowski, the longtime Museum of Modern Art (New York) director of photography and one of Winogrand’s great champions—he included Winogrand in his pivotal “Mirrors and Windows” moma exhibition in 1978 and called him “the central photographer of his generation”—did his friend the service of developing the leftover rolls. Likely Szarkowski was hoping for the same thing every photographer, amateur or professional, wishes to find: some flash of magic, some perfect picture. Possibly he was looking for a finale of sorts, a lasting revelation, a reframing, even, of Winogrand’s legacy. But Szarkowski was so disappointed with the results that, according to the New York Times, he likened Winogrand’s latter-day blast of film to “the sputtering that an overheated car engine continues to make after the ignition has been turned off.”

Winogrand may not have entirely disagreed. He once referred to himself as “a mechanic.” “I just take pictures,” he said. Read that as a self-deprecating statement or take it another way: Mechanics fix things, too. That’s not to say that Winogrand fixed the world he took pictures of—or that any photographer could do so. But he did practice a relentless form of looking that was free of expectations about what he might discover. The first time I met William Eggleston, he claimed that Winogrand—his “compatriot”—had so trenchantly captured New York City that he himself rarely shot pictures when he came up from Memphis. “Those streets were Garry Winogrand’s world,” he told me. “Garry set a tempo on the street so strong that it was impossible not to follow it,” Winogrand’s friend Joel Meyerowitz once said of his improvisatory shooting style. “It was like jazz.” By placing his faith fully in his ability to chase what lay before him, Winogrand uncovered a kind of accidental grace. As Geoff Dyer puts it in his new book on Winogrand, “Has anyone so consistently chanced upon the random glamour of the street?” That’s a necessary kind of vision that is in short supply, even—or especially—now that the world is awash in images.

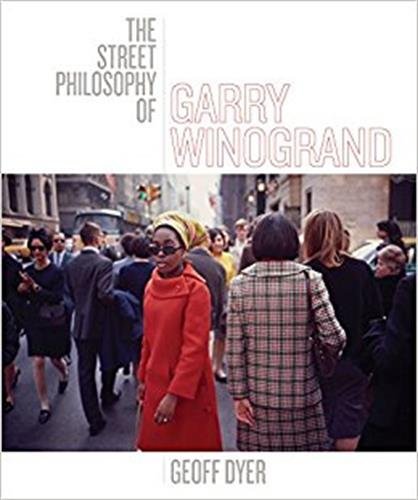

In 2003, Szarkowski republished Winogrand: Figments from the Real World, the first comprehensive overview of his work; apart from SFMoMA’s catalogue ten years later, it remains one of the photographer’s few major volumes. The dearth of available images from that vast archive is part of the impetus for Dyer’s study, The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand, which reproduces one hundred photographs from the Center for Creative Photography’s archives, paired with one hundred page-length essays. Dyer was inspired by another book of Szarkowski’s, simply titled Atget (2000), in which the curator selects and eloquently elucidates one hundred images of the French photographer’s work; words and pictures sit side by side. In fact, Dyer told Janet Malcolm in an exchange originally published in Aperture, “I hope I won’t go to my grave without having done a similar kind of book myself.”

Szarkowski dedicated his life to photography; Dyer has written smart and refreshingly unacademic work on the subject in 2005’s The Ongoing Moment, his exploration of canonical artists (Stieglitz, Strand, Lange, Arbus, Evans, Eggleston); and in What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney (2007). Dyer’s writing on photography exists in a body of work that willfully defies genre or definition: Among his published titles are four novels and numerous collections of unclassifiable essays, including a book about John Berger, who, Dyer writes, “had got me interested in photography, who had pulled down the bars separating imaginative writing and commentary, who had opened my eyes to new ways of writing.” The places where Dyer starts—whether with Berger, jazz, D. H. Lawrence, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker; traveling to see the Northern Lights; or life on the USS George H.W. Bush—are often little indication of where he’ll wind up. With Dyer, readers know it’s not about the purported destination but the running narrative of this crankily funny and deeply observant driver, the back roads, the sudden shifts. In this new volume, he combines that gleeful riffing with nuanced, frequently revelatory but occasionally flip takes on a revered and essentially mysterious photographer.

In a roughly chronological sequence, Dyer considers photos from Winogrand’s strongest and most influential bodies of work—especially his images of streets and airports. He revisits some of the best-known pictures (his 1964 photograph from White Sands, New Mexico, for instance, in which “everything urges us toward a point on the horizon—even though there is nothing there”) and aptly dissects classic street scenes, lingering on the artful arrangement of his subjects with the car windshield as frame and portal. He also rediscovers some of Winogrand’s plainer but still resonant photographs—a crowd of children plopped down in front of a department store TV, a woman standing by her car, parked in the garage beneath a neat, split-level home, under a clear, flawless sky—noting how Winogrand criticized Robert Frank for missing “the main story” of the 1950s: “the move to the suburbs.” Of that woman standing in her garage, Dyer writes, “Something in the picture subtly introduces an almost inaudible ticking.” He is insightful on the transitions in Winogrand’s career. His earliest forays into color are illustrated by a wonderfully weird photograph, circa 1964, of a monkey seated in the back of a blue convertible, gazing at an orangey-red cheese pizza. (“If any photograph deserved to appear on the cover of a book about the advent of colour, surely it’s this one,” Dyer notes.)

Dyer loves to mix genres, peppering his text with references to fiction and film. He mentions figures such as Spike Lee and Elena Ferrante, nodding to an audience who will appreciate the idiosyncratic references. For a 1950s picture of four men “peering into the oily confines of an engine,” he quotes the Joy Williams story “Congress”: “Car guys are kind of interesting. . . . They can be really hypnotic, but only when they’re talking about cars, actually.” And Dyer is drawn to the expressions Winogrand catches on his subjects. In describing one couple, who clutch each other in a cinematic expression of shock, Dyer quotes Philip Roth, characterizing their gaze as a reaction to “the relentless unforeseen.”

Dyer is pleasurably observant of the smaller, stranger details lurking in Winogrand’s work: An unoccupied chair in an airport is “shiny with emptiness”; a pile of rugs in a window display in 1960s London “lies there like an octopus with those two dark eyes and a mass of tentacles.” He catalogues some of Winogrand’s eccentric talents. For instance, he was “a wonderful photographer of feet,” and it’s true, particularly in a picture of four older women on the cusp of crossing a line in the sidewalk. Also, phone booths: The book includes a portrait of Winogrand himself in one, and it’s a delight; you could practically caption it with his friend Lee Friedlander’s great quote, “He was a bull of a man . . . and the world his china shop.” Sometimes Dyer makes particularly imaginative claims about the photographs: A giant man with his hand on the shoulder of a much shorter woman is envisioned as a possible encounter between Arbus’s famous giant, Eddie Carmel, and his parents—a lovely idea to consider. Counterculture street scenes mingle with the utterly cinematic—a black-and-white ’60s shot of a woman waiting at a rural bus stop in Scotland, a seemingly simple but arresting picture of a woman walking down a busy street in muted color. “This picture tempts us to go further,” Dyer writes, “to make the wild but plausible claim that in his colour work we glimpse the infiltration of the everyday by the cosmic.” It’s a beautiful line, inspired by a 1977 Leo Rubinfien essay on Winogrand’s “galaxies of detail,” but Dyer doesn’t explain further.

It’s unfortunate that Dyer frequently seems as restlessly eager as Winogrand to move on to the next frame. While some of his wildest, oddest claims are his most revelatory, his more plausible assumptions can seem weirdly off base. Dyer’s once-charming, carefree style sometimes falls flat: It occasionally reads as tone-deaf or simply rushed.He wonders whether the bandaged nose of one woman is the result of cosmetic surgery “to render herself more beautiful to male eyes”—as if this was the only likely cause. Next to a photograph of a woman in a striking red coat on a crowded street, he writes, “It was only recently that a black woman was able to walk with such confidence, affluence, and pride”—commentary that feels condescending. Haven’t black women been walking with confidence, affluence, and pride for centuries, regardless of what anyone else—including Dyer—thinks or says or does to them? Elsewhere, in a response to a 1970s New York image, why is an African American man described as a “black cat”? Maybe this is Dyer the stylist ironically trying to channel the language of the time, but it comes off as ludicrously presumptuous. A stale sense of irreverence can lead to lame attempts at humor: He describes a man sitting atop a trash can in Hollywood as being “born under the sign of Jack Daniels or Skid Row,” and another woman and a “black guy” as “half-way to cloud-cuckoo-land.” On the basis of a split-second shot, it’s impossible to gauge these things and unfair to do so. Besides, what’s the point, when there are other “galaxies of detail” compelling our close attention?

“When things move,” Winogrand once said, “I get interested.” Trying to choose an ending for his career is as overwhelming as knowing where to begin. You don’t want to still the perpetual motion. Dyer lands, in the closing sections, with a wisely sequenced and affectingly assessed selection of Winogrand’s work, a winding down. It’s largely chronological, so these are among the last things his camera saw, even if he never proofed the contact sheets. Here are his final years in Los Angeles, pouncing rapaciously on Hollywood, on the boardwalks. Here is the sole inclusion from Winogrand’s “Animals” series, two children swinging on a fence at the zoo. A park in heavily dappled sunlight evokes Renoir, making an eerie segue into the next photograph: a crowded departure lounge at JFK Airport that Dyer likens to “an ante-room of death.” The spiraling, nearly concentric rows of seats are full of passengers “waiting to be transported, in huge numbers across the river Styx or Lethe.” In the SFMoMA catalogue this is the final image; Dyer refuses to end his book on Winogrand with it: “We can’t leave him stranded here.”

A melancholy sequence follows—a face of a man that Dyer imagines could be in a Philip-Lorca diCorcia photograph, or a Jeff Wall. He includes a posthumous print from Winogrand’s later years that Szarkowski would label “a creative impulse out of control”: a slightly blurry photograph of a woman lying slumped on a busy street as a Porsche drives by. Was her situation considered too unremarkable to warrant stopping? Dyer wonders. An earlier Winogrand might have stopped to make a more trenchant image—elsewhere in this book, even, Dyer includes photographs of bodies in streets, surrounded by crowds of onlookers. This time, for whatever reason, Winogrand doesn’t stop. “But hadn’t Winogrand lived for long enough within the process of photography as to have become his camera?” Dyer writes. “Things could be recorded without being seen.” It’s a chilling suggestion—that Winogrand’s prowling camera prefigured the Google Street View cars, and that the camera had begun to erase the existence of the photographer.

The book concludes with another posthumous silver gelatin print, also from the Southern California period, also from Winogrand’s last years. With this photograph— “a dizzy geometry” of twin staircases, sunlight, and shadows; an old man slowly climbing the upper steps, gripping the rail; a young couple sitting in the sun on the lower stairs; Winogrand’s figure hovering above, between them, in shadow—Dyer lands at a transfiguring, bittersweet truth. For this picture is classic Garry Winogrand, a study in ephemerality and a testament to his towering legacy. More erasure. If he’d waited a moment or two later, Dyer notes, all the figures in this photograph would have been gone: “As will the light. Soon, there will be nothing left to see.”

Rebecca Bengal is a journalist and fiction writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, The Believer, Aperture, the Paris Review Daily, and NewYorker.com.