On July 6, 1962, a group of young upstarts presented “A Concert of Dance” at the Judson Memorial Church, which stands on the south side of Washington Square Park in downtown New York City. More than three hundred people gathered to watch the show—an impressive number given that every performer on the bill was somewhat new to the scene. Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, David Gordon, and Deborah Hay were but a few of those whose pieces that evening, to quote critic Jill Johnston, felt as though they “could make the present of modern dance more exciting than it’s been for twenty years.” Throughout the ’60s, Judson Dance Theater, as it was known, became one of those rare crucibles that produced and supported not one but multiple creative pioneers. Six months after that first concert, a press release stated that the work presented at Judson didn’t “so much reflect a single point of view as convey a spirit of inquiry into the nature of new possibilities.” That spirit fueled Judson’s incandescent aura, one that burns just as brightly more than fifty years later.

The catalogue accompanying “Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done,” the Museum of Modern Art’s retrospective of this wellspring of American experimentalism, aims to capture Judson in the round. Wishing to push beyond the usual salute to the canonized and their masterpieces, both the exhibition and the book compose a portrait of a place and time from the scattershot shards the artists left behind. Introductory essays by Ana Janevski and Thomas J. Lax, the curators of the exhibition, anchor the catalogue, setting the stage for the reader, contextualizing how and why Judson erupted, while contributors Adrian Heathfield and Danielle Goldman flesh out two of its root influences, writing about choreographers Anna Halprin and Merce Cunningham, respectively. Texts by Malik Gaines, Julia Robinson, Benjamin Piekut, Kristin Poor, and Gloria Sutton feature players and productions apart from Judson’s most lionized choreographers and dancers, considering subjects such as the music that was performed and produced there and the emergence of what Poor terms the “sculptural prop.” And a “Judson Handbook,” which includes a selection of annotated works as well as a map of “sites of collaboration” around the city, playfully points out that “downtown” wasn’t always an aesthetic; it was once a vibrant and creative neighborhood for artists. No record is ever complete, of course, and history is only the sum total of memory, objects, images, films, documents, and other partial proofs of life. And when disparate narrative threads are loosed, and allowed to tangle and occasionally tighten rather than be tied neatly together, a story reads differently. Admitting the gaps in our knowledge—surrendering to the inevitability, and even the virtues, of forgetting—is, as it turns out, how best to honor the ephemeral, collapsible nature of performance itself.

In all ways, the Judson artists reveled in liveness, treating the passing of time not as an existential burden, or a horrific human fate—ah, me!—but as an energetic release into creating and experimenting free from the pressures of permanence. The list of Judson’s participants is long, including composers and musicians (John Cage, Cecil Taylor, La Monte Young, Charlotte Moorman), visual artists (Robert Rauschenberg, Red Grooms, Ray Johnson), performance artists (Eleanor Antin, Joan Jonas), writers (LeRoi Jones, Diane di Prima), filmmakers (Storm de Hirsch, Gene Friedman), and many more. Some of the performances presented at Judson were thrilling, adventurous, brainy. Just as often, a presentation could look slight, even sloppy. Not infrequently, the pieces were just plain old boring. (Apparently, Paxton’s dances were renowned for the patience they demanded of an audience, who almost unanimously conceded that he was, if nothing else, a terrifically handsome man.)

If there was a single guiding principal (and there wasn’t, really), it was the pursuit of a new virtuosity, achieved in part by the rerouting of attention. Young, considered the first Minimalist composer, dove into sustained sounds, some of which were made without instruments; his Poem for Chairs, Tables, Benches, Etc. (1960), required that his performers push the furniture around the stage, the squeaks and rumbles offered as another kind of music. In Carolee Schneemann’s Chromelodeon (4th Concretion), 1964, the gestures and energies of drawing and painting were translated into movement, creating a frenetic and joyous assemblage of performers, each of whom she imagined as the embodiment of a different color. The dancer and filmmaker Elaine Summers’s Fantastic Gardens, also 1964, entwined film projections and live action inside the church—a watershed moment in the evolution of intermedia art.

The Judson choreographers’ innovations were, from the go, labeled “pedestrian” (albeit misleadingly) for the ways in which they rejected modern dance’s grandiose gestures, instead exploring a physical mastery that was more nuanced, and grounded in an essential question: Why is this dance but not that? Yvonne Rainer’s We Shall Run, 1963, was performed by a dozen or so dancers and civilians wearing plain clothes and dashing around the space, moving, assembling, and dissolving into various patterns. While Rainer’s steps were simple enough—one foot in front of the other—the patterns were intricately designed and had to be precisely executed. The rejection of traditional technique allowed for the development of another standard or form. In Satisfyin’ Lover, 1967, Paxton directed forty-two people to walk across the stage so audiences could closely observe a rudimentary movement and see the singular ways in which a wide variety of bodies execute the same act.

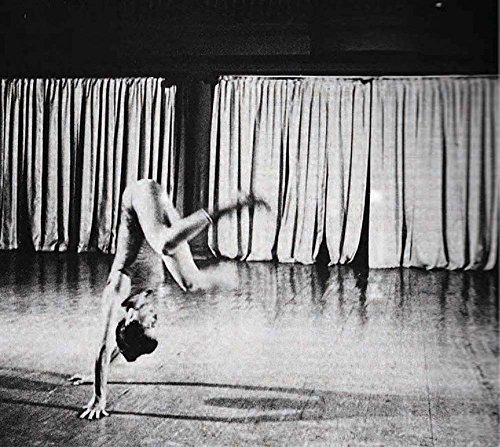

Part of the Judson ethic was to dissolve the distinctions between audience and performer—between high art and everyday life. We are all observers, we are all performers; in effect, attention is the craft that unites us. For the live arts, the audience members are more than a mere memory cache; they are its interpreters, its record keepers. The story of Judson would be far less vivid without the brilliant contributions of its equally radical attendees, and the exhibition catalogue recognizes some of Judson’s most essential spectators. Portfolios of selected images by the photographers Al Giese and Peter Moore prove how invaluable, and at times inconclusive, a document can be. Giese, then on staff at Newsweek, shot a number of performances with the hawk-eyed clarity of a photo-journalist, trying to capture all as legibly as possible. Moore’s images are more atmospheric, appearing perhaps more personal. Moore wasn’t at Judson on assignment; he and his wife, Barbara, attended shows out of a curiosity (his), and a love (hers), for dance. He shot on his own dime and in his own time, allowing his experience to be his guide, immersing his eye in what was unfolding around him. His photographs—sometimes blurry, oddly composed, or rich with inscrutable actions—are as expressive as they are eloquent.

And then there was the mighty Jill Johnston, a dance writer for the Village Voice, the first openly lesbian journalist in America, and in many ways the writer of record for Judson. In her weekly column, “Dance Journal,” she covered performances by Rainer, Trisha Brown, Robert Morris, James Waring, Lucinda Childs, and others. These pieces were later collected in Marmalade Me, 1971, a touchstone tome of performance criticism, which the catalogue rightly celebrates as an artistic achievement in its own right. Her perambulatory mind, her swerving sentences, were the perfect match for the rigorously open spirit of the era. The present-tenseness of her prose kept time alongside her subjects, while never abandoning the darting rhythms of her own instincts. For her, as for the Judson artists, life and art and music and dance wound around each other seamlessly.

Of Paxton’s Afternoon (a forest concert), 1963, which he staged in a suburban wooded area, Johnston wrote: “I wasn’t keen about the dancing. . . . The scene I thought best suited to the environment was a sweet transaction between mother, son, sky, and trees when we were led to a clearing where Barbara [Dilley] Lloyd sat with her baby, Benjamin, who played with a leaf, hugged his mother, glanced imperturbably at the spectators, and took a big view of the sky.” Johnston’s goofball charisma—she was apparently always the life of the party—earned her a spotlight of her own. She performed at Judson on many occasions, too, and starred in one of Andy Warhol’s earliest films, Jill and Freddy Dancing (1963), in which she and another downtown darling, Fred Herko, swanned around and hammed it up together on a Manhattan rooftop.

Some of the most poignant stories from the Judson era are its least lasting—threads perhaps too short to weave into legacy. The catalogue also memorializes some of those who might have been forgotten, Herko among them. A classically trained pianist as well as a dancer, he was a cofounder of Judson Poets’ Theater. He choreographed and danced at Judson, usually in humorous solos in pieces such as Binghamton Birdie, 1963, for which he glided across the floor on a single roller skate wearing a sleeveless T-shirt with the word judson printed across it. With his boyish good looks, he starred in a number of other Warhol films, including The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys, 1964. Poet Diane di Prima, his great friend, captured his particular self-possession with this adoring jab taken from a verse written for his birthday: “You are sure you are perfect.”

Magnetic on stage, he even managed to astonish the audience at his premature death in 1964. High on methamphetamines, Herko jumped through an open window in a flawless jeté. His friend John Dodd, who was there, reported that Herko had aimed his leap so superbly that not even a hair on him grazed the window frame. There is a dark sort of flair in turning tragedy into an apocryphal tale, and weighing this story for all it might yield now raises a question. Why dedicate oneself to performance? One possible answer: to rejoice in the exquisite and transitory windfall of life.

Jennifer Krasinski is a senior editor of Artforum.