WHEN WAS the last time you picked up Sweet Charlatan, Frost in May, Is She a Lady?, or The Departure Platform? Do the names John Heygate (author of Decent Fellows), Inez Holden (Born Old, Died Young), or Jocelyn Brooke (Mine of Serpents) ring a bell? One side effect of reading Anthony Powell: Dancing to the Music of Time, Hilary Spurling’s biography of the long-lived (1905–2000) British novelist, is realizing how many writers in his various circles have passed entirely out of civilized memory. Doubly sobering, for some of us, is the possibility that his books might be joining this invisible library. Malcolm Muggeridge, once one of Powell’s closest friends, asked rhetorically: “Will posterity . . . see in his meticulous reconstruction of his life and times a heap of dust? . . . Honesty compels me to admit it might.”

Though every word of Powell’s fiction—the twelve-volume A Dance to the Music of Time, plus seven other novels—is available in America, he lacks the name recognition of his staunch admirers Evelyn Waugh, Kingsley Amis, and P. G. Wodehouse, all of whom predeceased him. His comic gifts rival theirs, but perhaps the very ambition of the Dance makes him seem like an all-or-nothing proposition, the antithesis of pleasure reading. To be a Powellite is to read no fewer than a million words: a dance to the music of time management.

The sequence commenced in 1951 with A Question of Upbringing and eventually spanned four trilogies, concluding with 1975’s Hearing Secret Harmonies. All twelve books are narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, whom Spurling calls “colourless”; even Powell’s wife, Violet, worried about his “lack of identity.” Yet Jenkins is more than a cipher: First of all, would a cipher get invited to such good parties? His most attractive trait is a deep, almost insatiable curiosity about people, suitable for a book that’s about everyone else: writers and artists, magnates and eccentrics, all brought to life with a refreshing lack of judgment.

Most profoundly, the scale of the Dance allows Powell to capture something of the way life is actually experienced, as characters weave in and out of view, like moons with irregular orbits. (I know what Michael Frayn means when he writes, “It altered my perception of the world”: The sum effect is cosmic.) A hundred pages into A Question of Upbringing, Powell already grasps the size of his canvas. After sharing a train ride with a fellow houseguest of his school friend Peter Templer, Jenkins observes: “He piled his luggage, bit by bit, on to a taxi; and passed out of my life for some twenty years.” The mysteries of time itself seem bound up in that semicolon.

Waugh declared Powell’s roman-fleuve “more realistic” and “much funnier” than Proust’s, itself a very funny thing to say. The humor could pose health threats. Spurling quotes a letter describing the reaction of Powell’s brother-in-law: “He was speechless, choking, purple in the face, rolling on the old sofa in the drawing-room here & breaking the springs, & his tongue was rolling outside his mouth. . . . Whenever he seemed to have recovered for a moment, he had a relapse again, like hiccups.”

Limitless relapses awaited the devotee. Each fresh installment—brought out on average every two years, and attractively compact at around 250 pages—could cause dinner-party arguments to erupt “with the sudden fierceness of a civil war.” Powell completed the Dance at age sixty-nine. Other books followed, notably four memoirs. But a new generation had already started to see him as reactionary and irrelevant (“elitist, class-ridden . . . written by a snob,” as one reader described his first encounter with the work), and by the 1990s, Spurling writes, Powell had “come to stand for everything dull, conventional and socially exclusive to a younger generation who had never read him.”

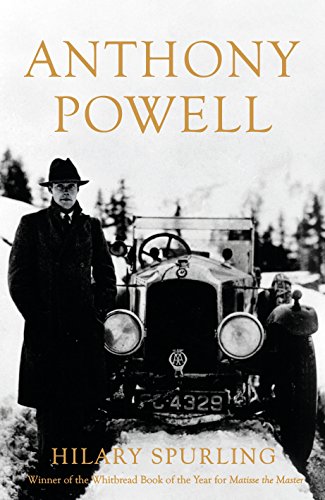

The dust jacket of Spurling’s biography poignantly suggests the reader “SHARE: #AnthonyPowell”; few hashtags seem less likely to go viral. Over the course of her attentive, occasionally revelatory book, Spurling (who first met Powell while working at The Spectator in 1969) doesn’t make outsized claims for her subject’s relevance. Instead, she keeps the action brisk by illuminating Powell’s social world, putting his many books in context while sidestepping spoilers, and probing psychological depths he himself avoided in his memoirs. With access to papers unavailable to Powell’s previous biographer (Michael Barber, whose 2004 Anthony Powell: A Life left little impression), Spurling has executed her own sort of dance to the music of time: a book embarked on with its subject’s blessings, finished long after his death.

One of the perverse things about Jenkins is how little he reveals about his wife (and later, children). Everything appears reasonably steady on the home front, the dramatic stakes low, all the better to illuminate the colorful ménages forming and dissipating around him: doomed love affairs, acrimonious splits. Powell married Lady Violet Pakenham in 1934, and they stayed together for over sixty-five years. Unlike Jenkins, whose one torrid passion (for his friend’s sister, the married Jean Duport) haunts him periodically through the years, Powell had numerous romances and affairs before tying the knot, and Spurling rescues these often unconventional women, at least for now, from oblivion.

Out of Oxford, Powell found himself with “no prospects, no connections, nothing to inherit,” rendering him invisible in the “world of debutante dances and court presentation.” All the better: At twenty-two, he fell for Nina Hamnett, an artist and model sixteen years his senior who “combined absolute recklessness in her personal life with tight professional discipline.” (“Finding a way of killing Sunday afternoon is half the battle,” she said, going to boxing matches to offset the doldrums. Who could resist?) Hamnett connected Powell with people “up and down the social spectrum,” one of whom provided an introduction that led to lunch with occult wild man Aleister Crowley. Other lovers and muses include Juliet O’Rorke, the artist wife of the New Zealand architect who did the ship interiors for the Orient Line, and the dramatic Varda, translator and bookstore owner—“hard to please, subject to sudden destructive spurts of rage or despair.” His last affair began the week before he met Violet for the first time, at her brother Edward’s castle in Ireland. One of the other houseguests was Mary Manning, a Dublin journalist and playwright, who had cast an ex-boyfriend as “Horace Egosmith” in one of her plays. He liked it so much that his interest drifted from fiction to drama. His name was Samuel Beckett.

In contrast to the women in Powell’s life, many of the men he knew remain boldface names. The novelist Henry Green was a formative influence—but at age ten, when he was still Henry Yorke, and lived in the same dormitory as Powell. There, the two were “like professional narrators of the orient,” assigned by their eighteen bunkmates to tell stories after lights-out. Spurling notes that Powell and Waugh actually became friends not at Oxford (they were a few years apart) but at a humbler institution, Holborn Polytechnic, where in the fall of 1927 Powell took a printing class, while Waugh was looking into carpentry, in case the writing didn’t take off. (Powell, then working at Duckworth, was responsible for bringing out Waugh’s first book, a study of Rossetti.) In the ’40s, he became close to George Orwell, the Powells sometimes providing childcare for the Animal Farm author’s son after his first wife died. (Powell’s own sons’ playmates included Jane Asher and Joan Collins.)

Of the lesser lights, I never tire of reading about Julian Maclaren-Ross, that “literary editor’s dream, and nightmare,” whom Powell met while an editor at Punch. A chronically broke dandy (cane, dark glasses), he lived nomadically in Fitzrovia, switching hotels depending on his financial situation. His top-notch copy was written between closing time and 3 am in a tiny, “exquisitely legible, non-cursive hand as artificial and fastidiously disciplined as his entire persona.” He would give editors detailed lists of all the articles he could/should write for them and tie up the phone for hours. The portrait ends with a scene circa 1954, in which Maclaren-Ross confesses to Powell that a woman has driven him “to the brink of madness.” Her name being “too sacred to mention,” he scribbles it on a piece of paper. (The unreciprocated crush was on Orwell’s widow, his second wife Sonia.)

The jobbing journalist became the model for X. Trapnel, one of the beautiful losers who populate the Dance, and Powell would use this encounter, at once hilarious and wrenching, in the tenth installment (Books Do Furnish a Room, 1971, which backdates the event to 1947). To be close to Powell was also, possibly, to be transposed into his grand fictional project.

IF JENKINS is “colourless,” was Powell himself? “I was brought up to do ordinary things,” he told the New Yorker in 1965. “My parents insisted on that. I was brought up to think drawing attention was a bad thing.” He was the only child of an unconventional pairing. His mother, Maud, met his father, Philip, when she was thirty-three and he was eighteen, and they married a few years later. Philip, a career military man, was prone to rage, leading to his son’s lifelong resentment. The colonel helped out with money, especially when grandsons came into the picture. But his “emotional blackmail” and vacillating moods infuriated Powell, as when a missive arrived from the colonel explaining his own financial straits in all caps (“I BEG YOU TO TREAT THIS LETTER AS ONLY PUTTING YOU INTO THE PICTURE”), then confiding, “your mother doesn’t know & must never know.” The next letter went overboard with optimism: “Things may buck up a bit, & you may make a fortune out of your next book!”

This Oedipal friction, undetectable in the Dance, gives the biography its grit. Yet I sometimes felt Powell should have given his old man a break. When Powell left school, Philip made an arrangement with his former second-in-command, Thomas Balston, now editorial director at Duckworth. Philip would subsidize his son’s salary over a three-year term, at the end of which Powell would be made a partner. When the colonel refused to pay the last installment, Balston went ballistic, and Powell’s progress at Duckworth was blocked for good.

But still: Being there gave him a street-level view of the making of books, professional knowledge that would serve as subject matter for the Dance and more immediately What’s Become of Waring, his 1939 satire of the publishing world. (“Bernard began to loathe books, so that it seemed he had only entered the trade to take his revenge on them. His life . . . became one long crusade against the printed word.”) It also gave him the rare opportunity to essentially direct the publication of his own debut novel. At twenty-five, Powell sold Afternoon Men to Duckworth for £25, and took over every aspect of its production, from reading the proofs to assigning the severely modernist cover art. After he had himself become a father, Powell would complain to Violet about the colonel’s miserliness. But when Philip passed away in 1959, it was revealed that he had invested his capital so well that Powell inherited over a million and a half pounds (in today’s money), allowing him to live, for the first time, with financial stability. “This was the last thing he had anticipated,” Spurling writes. Five books of the Dance had been completed; the money led him to rethink the scope, from six to twelve volumes.

How did he hold it all together—thousands of pages with a single narrator, with hundreds of characters: twenty-five years of work covering at least twice that span? The most indelible passage in Anthony Powell: Dancing to the Music of Time describes the “monstrous collage” with which Powell, in 1964, covered the walls of the boiler room in his home, the stately Somerset pile known as the Chantry. Here we see

human figures out of ads, catalogues, Christmas cards . . . [stuck] together in a seething jumble: incoherent, shapeless, meaningless, and pulsing with raw energy as if he had simply emptied out the contents of his imagination on to the space in front of him. . . . Above the main boiler pipe a crowd of women of all kinds and ages swarm round William Shakespeare. . . . Proust’s pale face above the mirror is sandwiched between the Byzantine Empress Theodora on one side, and Joseph Stalin on the other. . . . As the tide of images rose up the walls, Tony climbed on chairs and brought in ladders. . . . There is something elemental, even horrifying about the scale and impact of this torrential outpouring.

It’s a breathtaking glimpse of Powell losing control, like someone screaming into a bag: the fury of his father, perhaps, sublimated, pushed literally underground, and expressed in a dazzling visual nightmare. Spurling calls it “a display without limits, hierarchy or borders, like the sea.” As crisply constructed as the Dance appears on the surface, it shares that oceanic power—to read it is to let it flood the rest of your life.

Ed Park is the author of Personal Days (Random House, 2008). He wrote the introduction to Powell’s Afternoon Men (University of Chicago Press, 2014).