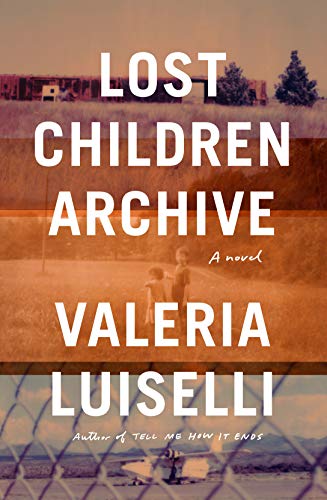

Valeria Luiselli began volunteering as a translator for children in immigration court around five years ago. Drawing on that work, and the activism that followed, she wrote two books: Tell Me How It Ends, an extended essay based on the questionnaire used to interview the children, and her latest, Lost Children Archive (Knopf, $28), a novel about a family traveling by car from New York City to Arizona so that the father, an audio documentarian, can work on a project about the Chiricahua Apache. During the trip, the mother becomes obsessed with news on the radio of migrant children being deported from the US. The novel unfolds in a plurality of voices, sounds, and stories, including Elegies for Lost Children, a novel-within-the-novel made up of a pastiche of other migration and travel stories.

ALEJANDRA OLIVA: Lost Children Archive layers several narratives over the primary one of a family going on a vacation. You have the Apache Indians, and you have the children in the desert. There’s this road-trip narrative—which I think is very much a trope of American literature—and also past and present atrocities wrapped up in the splendor of the landscape. How did the different threads of the novel come together as you were writing?

VALERIA LUISELLI: I didn’t want the story lines to be neat and tidy and symmetrical, but rather to reflect each other through allusion and juxtaposition. There are a lot of echoes in the three different narrative strands: the woman narrator, the boy, and the Elegies for Lost Children. There are a lot of rhythmic patterns, and images that repeat. One parallel that is not quite a parallel but rather history, getting repeated over time: I’m referring to what was done to Native Americans in this country—they were banished, sent to reservations, or “relocated”—and what is being done to the mostly indigenous people from Central America who have come to the US, where they are relocated to detention centers or deported. The book isn’t only about relocation, deportation, and political violence, but it does offer a meditation on the nature of history. Historical wounds that are not looked at and reckoned with do not heal.

You also talk a lot about history and repetition in Tell Me How It Ends, writing that “The only thing to do is tell it over and over again as it develops, bifurcates, knots around itself.” Can you say more about what Lost Children Archive is doing in the work of telling and retelling these stories?

I think both books are an intervention in the wider dialogue about immigration, and a way of showing that dialogue doesn’t finalize any discussion. We need to be having a discussion about what is happening, not only at the US border, but in the US more widely, with the brutal, institutional, legalized violence against people that are coming here legally and then being illegally stripped of their rights to due process and incarcerated. (It is perfectly legal to arrive in a country seeking asylum.) It’s a conversation we need to keep having in many different formats and spaces. I think it’s crucial to continue to document things every day, to talk about the many nuances, to continue discussing beyond the moment in which a crisis reaches a peak and makes it to the headlines. Situations such as these require a population to be constantly alert, and thinking, and writing, and discussing these issues.

In your novel you make reference to real people and organizations, such as Still Waters in a Storm and the New Sanctuary Coalition, that have been working to help immigrants and resist deportations. Are you hoping that readers will participate in the archive you’re building, and also contribute to organizations that are helping immigrants?

I don’t have anything planned out for the readers, to be honest. It was different when I wrote Tell Me How It Ends, because it was very clear to me what I was doing. I was denouncing a situation, and I was denouncing it in the moment in which that crisis had ceased to be talked about, after a summer of a lot of headlines about the rising rates of deportations. I wanted a different kind of intervention and I was putting forward a political stance. But a novel is just a different kind of animal. I have had to negotiate a lot with myself in terms of what political expectations I can or cannot have when writing fiction. Naming these organizations in the novel was not a gesture toward generating a particular response so much as a way to amplify the particular circumstances that I was writing about. I wanted to show different sides of the issue and very local responses to institutional violence against undocumented people.

You started working on Lost Children Archive during the Obama administration, when we were seeing the rapid deportation of child migrants. Since Trump’s election, there have been huge changes in policy, greatly increasing the scale and brutality of deportations, which has affected people on the ground. How did the meaning of the book change over time to reflect the political situation?

I decided early on, maybe not even at a very conscious level, that the novel was not going to be updated to coincide with political events. Tell Me How It Ends has had a couple of updates since its first publication. It has had layers added onto it—from its first publication as an essay in Freeman’s magazine to when it became a book—because the circumstances were changing so rapidly and I wanted to be as precise and up to date as possible. Even with those updates, that book is to a certain degree outdated, because the situation has gotten so much worse. I started out writing about children whose childhoods are lost and children who couldn’t tell their own story. But now, with the Trump administration’s new policies that separate detained families, the phrase “lost children” has acquired a very different connotation. It’s unfortunate to think about what is happening, but in terms of language and of power, the title offers a reminder of how potent language can be and how a term can gain multiple resonances over time. A term will always be re-signified, and in this case it got very quickly re-signified and now points toward something that I wasn’t thinking of initially.

Can you talk about the way that sound and voices and silence move through the novel? You achieve a plurality of voices and languages that seems to be part of your book’s very structure.

In the novel, stories are transmitted within the tiny community of the family, passed from one generation to the next. I also wanted to think about how storytelling can be a way of gesturing toward wider communities, and how we construct a collective worldview through the stories we tell. With this novel I was also trying to think about the politics of documenting and about sound—which voices are included and heard, and which ones get left out. Mapping is always a way of including as well as of excluding. I was interested in the question of how to think about the last group of Chiricahua Apaches to be sent to a reservation. And I was thinking about the voices of so many migrants who arrive here and are immediately confined, silenced. We hear very little of them, or we hear about them through a very tightly scaffolded narrative. Those stories too often become content that feeds an already existing perception of what an immigrant comes to America to do, or who he is, or who she is. There are many layers around the politics of documenting, and that’s what I set out to think about.

I actually got back from volunteering in Tijuana, at the border, about a month ago.

Oh, wow. How was it?

I’m still struggling to find words for what it feels like to watch a van full of people who are headed off into detention. It reminds me of the scene in your novel when the plane full of children takes off—all of those kids are being deported. I read that scene before going to volunteer, and then reread it after I got back, and it just felt so real in its sense of awfulness. Could you talk about that scene, and bearing witness, and making art out of bearing witness?

It’s difficult to come back from an experience like that and to go back to your life without normalizing what you’ve just seen at the border. It’s a reality that I’ve been trying to look at and live in for a long time, and it’s difficult to operate without just going crazy with rage and frustration and sadness. The only way that I can transform that heavy knot of feelings into something that I can live with is through writing, because that’s really the only thing I know how to do well.

For the past five years, I have had access to spaces, either community spaces or now more recently to a detention center for kids, and I understood at some point that what I could be more useful in doing there was bringing writing to those spaces. In court, when I was doing the translations and the interviews, I know that was useful, that they needed bodies in there doing that work. But now I’m focusing more on teaching writing in spaces of confinement.

Have you brought fiction into those spaces too? Or have you written fiction mostly after stepping away?

No, I think fiction can be very useful in detention centers too. Right now I’m teaching a creative-writing workshop in a detention center. It’s small—a group of fifteen girls—and I can only go once a week. But it is at least clear to me that writing is a very positive thing for the girls that I am teaching there. Mostly, I think it’s really important to stay active. If you start finding it hard to deal with the huge difference between the realities of there and wherever you’ve returned to now, I think staying involved is a way of staying sane, remaining politically coherent, and also doing something that’s valuable for others.

Alejandra Oliva is an essayist studying theology at Harvard Divinity School.