The polymath Dick Higgins once wrote that a book is “the container of a provocation.” With this in mind, he started Something Else Press in 1963, delivering a remarkable number of provocations to a mainstream audience before the imprint’s dissolution a decade later. Higgins packaged neo-avant-garde ideas in mass-market formats, producing books by contemporary artists like John Cage, Claes Oldenburg, Merce Cunningham, and Ian Hamilton Finlay. Something Else also reissued neglected works of the historical avant-garde in deluxe editions, notable among them Gertrude Stein’s vast, long-out-of-print novel The Making of Americans and Richard Huelsenbeck’s 1920 anthology of dada writings. And the press put out the Great Bear Pamphlets—short works by the likes of Alison Knowles, George Brecht, and Allan Kaprow—for two dollars each, in a size and format that might easily be photocopied. In addition to all this rather manic production, the Something Else catalogue promised items it could never deliver: Among the bruited but unpublished books were Oldenburg’s poems, Erik Satie’s collected writings, and an illustrated edition of Stein’s Before the Flowers of Friendship Faded Friendship Faded.

Higgins was an artist, poet, theorist, and composer, as well as a tireless raconteur of his own avant-garde history; his intention, he wrote, was “to publish source materials in a format which could encourage their distribution through traditional channels, however untraditional their contents or implications.” Today, Higgins is primarily associated with Fluxus, the capacious and democratic artistic movement that from the early 1960s onward aimed to smudge distinctions between object and event, art and the everyday. In this new and fascinating selection of his writings, Higgins, who died in 1998, retells the story of how Something Else Press came about. George Maciunas, cofounder of Fluxus, had promised to publish Higgins’s book Jefferson’s Birthday, a complete collection of all Higgins had written, good or bad, between April 13, 1962, and the same date a year later. While Maciunas dithered, Higgins told Knowles—they were married, twice—that he’d like to start his own publishing house and call it Shirtsleeves Press. “That’s terrible,” she replied. “Call it something else.”

Higgins, who was born in 1938, liked to say that his first word was hypotenuse. His family owned and ran a steel plant in Massachusetts, and Something Else was funded by an inheritance he received in his mid-twenties. Arriving in New York in 1958, he studied music with Henry Cowell at Columbia and with Cage at the New School for Social Research. In Cage’s class, he met future Fluxus artist Brecht; he then met the mail artist Ray Johnson in a café (after mistaking him for Jasper Johns). Higgins and Johnson “often wandered together through the Lower East Side, where he lived like a Troll under the Brooklyn Bridge investigating strange cheeses in jars or fishes in barrels.” Higgins met Maciunas in 1960, and Higgins and Knowles traveled with him to work on the first Fluxus festivals, in Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands. For the scant decade that it existed, Something Else Press was both an outlet for Higgins’s own writing and a prodigious contribution to the printed corpus of contemporary art, drawing a good deal from the Fluxus milieu. According to Higgins’s accounts of the period, he wore himself (and his inheritance) out putting this work into the world.

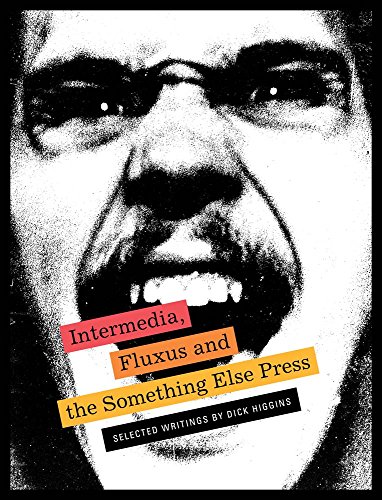

Alongside an illustrated checklist of everything Higgins published or planned to publish under his imprint, Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press contains twenty of his own texts: manifestos for his own and others’ interdisciplinary practices, reflections on visual poetry, and detailed (and sometimes unattractively score-settling) memoirs of the 1960s. Higgins emerges as an adventuring intellect who thrived on connections and collaboration. He was also a person of singular ambition and frequent resentments, with an autodidactic bent that, while admirable, can make him and his champions sound overreaching. After a dutiful introduction by editor Steve Clay, the book is prefaced with an essay by Higgins’s Fluxus colleague Ken Friedman, who makes some pretty wild claims for his friend. Friedman contends that Higgins’s work and ideas ought to be spoken about in the same breath as those of Cage and Duchamp, and that his relative obscurity means “his true stature as an artist will never be known.” That may be true, but it is harder to credit Friedman’s assertion that in order to grasp Higgins’s true brilliance we must go back to a figure like Erasmus of Rotterdam: “He was the kind of human being whose greatness rests on the natural dignity of moral grandeur.”

Friedman clearly shares Higgins’s propensity for overstatement, but at the heart of his essay is a serious argument for Higgins’s most important neologism, intermedia. In a 1966 essay of that title (published as the first Something Else Newsletter) Higgins wrote:

Much of the best work being produced today seems to fall between media. This is no accident. The concept of the separation between media arose in the renaissance. The idea that a painting is made of paint on canvas or that a sculpture should not be painted seems characteristic of the kind of social thought—categorizing and dividing society into nobility with its various subdivisions, untitled gentry, artisans, serfs and landless workers—which we call the feudal conception of the Great Chain of Being.

The initial observation is prescient, to be sure: Higgins’s “intermedia” describes not only traditional art forms that draw on more than one medium—he gives the example of opera—but new arts that simply will not resolve into constituent parts. Higgins’s idea is one predictor of our “post media” scene, in which artists move with assurance between different modes of making and the distinctions between object, installation, and performance can be abandoned at will. But note how swiftly he moves on to grand, or grandiloquent, claims about the “Great Chain of Being.” Much of his writing is like this: ranging about amid intellectual and artistic history with abandon, not always delivering much in the way of evidence. His essays—he claimed an allergy to the genre, but that is the best name for his vagrant texts—spark in so many directions, it is easy to see why his post–Something Else Ph.D. at NYU was left uncompleted. His scholarly or historical writings are actually heated polemics regarding the present. The best of these in Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press are his brief, dense accounts of the history of pattern poetry, which he reads (or sees) as prefiguring 1960s concrete poetry, a tradition he somewhat gleefully sets against the mainstream of progressive postwar American verse.

By the time Higgins abandoned his doctoral work in 1979, Something Else Press was a bitterly contested memory, but some of his retrospective writings about the publishing house are generous and informative. Among the less expected, and more conventional, pieces in the book is a lovingly detailed essay titled “What to Look for in a Book—Physically,” in which Higgins lays out the best practices in book design, from paper quality and typefaces to the best cloth for binding: “On relatively smooth or matte-finished cloths, notice the fineness of stitches and weight of the fibers.”

The piece has an unusual tone for a writer who is more frequently ironic and even scabrous. Indeed, throughout the rest of the book, many mainstays of the experimental arts scene come in for sly jabs or outright assault: He wonders whether Harold Pinter or Samuel Beckett is the modern J. M. Barrie. He frequently disparages Morton Feldman for self-imitation. And in 1982 he declares that “the best poems of the 1950s are being written today by John Ashbery & Co.” Complacent cultural movers, whether artistic or institutional, he mocks as “pudgies.” Elsewhere, especially in the texts that recount the demise of Something Else in the mid-1970s, he can come across as defensive and self-exculpating. His daughter Hannah Higgins, an art historian, explains in an afterword that he failed in life, and in print, to acknowledge the editorial contribution of Emmett Williams, who oversaw the press’s best-selling book, An Anthology of Concrete Poetry.

As Hannah describes, and as her father notes in a couple of essays, he had been an alcoholic for some years, and the collapse of Something Else Press coincided with one of several breakdowns Higgins suffered. In 1979, he and Knowles (divorced and eventually remarried) relocated to the Hudson River valley, where Higgins concentrated on painting. He died of a heart attack while attending a festival of intermedia art in Quebec. The force of Higgins’s personality, the sheer intellectual and organizational energy in evidence here, the insights into the group dynamics of Fluxus and related movements—all make Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press an essential volume. It’s an unruly guide to publishing and preserving one’s cultural present.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction is published by New York Review Books.