The first line of Carrie Fisher’s debut novel, Postcards from the Edge, is still one of the best opening volleys of all time: “Maybe I shouldn’t have given the guy who pumped my stomach my phone number, but who cares?” It is so good, in fact, that it only could have come from her—despite the fact that when Postcards was published, in 1987, the Los Angeles Times tried to foment a minor scandal about whether or not Fisher really wrote it. She had enlisted a good friend, Paul Slansky, as an “editor” of the book, and his name below hers on the title page was causing readers and critics a bit of confusion. Though Fisher vehemently denied that Slansky had cowritten any part of the book, the question of authorship made it all the way to Larry King’s show, where he asked her if the novel was secretly ghostwritten. Fisher’s answer was quick and definitive: “That’s sexist. . . . Ask Paul.”

It seems both misogynistic and willfully fatuous to assume she didn’t pour herself completely into Postcards. But for those still in doubt, we know the first line was hers, because it came from an actual stomach pumping in early 1985, when Fisher took too many tranquilizers while at home in Beverly Hills and summoned her best friend, the writer Carol Caldwell, and also Dr. David Kipper (the actress Teri Garr’s boyfriend and an addiction specialist) to come to her aid. When they arrived, they found Fisher half-conscious, staggering around in a fox-fur coat and “dripping with diamonds.” They eventually shuttled Fisher to a secret room at Cedars-Sinai, where Caldwell assisted the doctor because she and Kipper were worried that hospital staff would sell the story of an overdosing Fisher to the National Enquirer. Weeks later, after recovering from her flirtation with oblivion, Fisher offered Caldwell a Freudian explanation for her behavior. “You don’t know what it was like to grow up with Debbie and Eddie,” Fisher exclaimed, referring to her famous parents, Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds, who very publicly split up when Carrie was two years old. Caldwell, for her part, was no longer a sympathetic audience, feeling that Fisher was caught in a self-destructive loop. “Get over it!” she scolded Fisher at the time. “You’re a grown woman!”

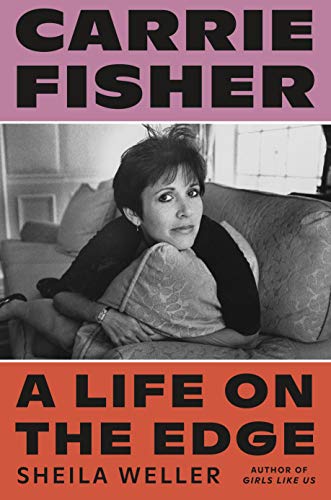

Sheila Weller’s Carrie Fisher: A Life on the Edge (Sarah Crichton Books, $28), a thoughtful and fast-paced biography, shows that even when Fisher was a grown woman, and an accomplished one at that—actress, entrepreneur, playwright, author—she was plagued with Peter Pan syndrome, which often comes with growing up with famous parents who have their own gravitational pull in the tabloids. Everyone in her life was vying for attention, all the time, leaving a young Fisher to make her own way. Her mother, Debbie, was America’s sweetheart, the perky proto-Gidget who tamed the crooner, at least for a while, until he ran off with her vampish friend Elizabeth Taylor. Reynolds’s story was one of pity followed by steely reserves. She picked herself up, cinched her girdle, and soldiered on for her kid. Eddie at first enjoyed a rakish reputation, but fans soon soured on his misdeeds, and within a few years he ended up with a canceled variety show and another divorce. Later, Carrie would process all of this drama the only way that she—and her parents—knew how: in public. In the 2001 television movie These Old Broads, written by Carrie, her mother plays a former film star, and Taylor plays a mouthy agent. The two women reconcile by gossiping about being married to the same man (off-screen, Reynolds and Taylor allegedly squashed their beef in the late 1960s when they were trapped together on a transatlantic cruise).

Few people could truly understand Fisher’s bizarre upbringing—and certainly very few of them are biographers. But Weller, a Vanity Fair contributor who grew up in Fisher’s neighborhood as the daughter of a movie-magazine writer and the niece of the owner of the buzzy Hollywood restaurant Ciro’s, is exactly the right showbiz insider-outsider to shepherd Carrie Fisher’s story to the masses. Weller has the bona fides and has proved herself as a popular Virgil of famous Boomer women’s experiences. Her 2008 book, Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—And the Journey of a Generation, was a smash hit, a nostalgic triple cherry on the cultural slot machine that became the (white, upper-middle-class) Mom Book of the year. She followed that up with The News Sorority, a triple biography of Diane Sawyer, Katie Couric, and Christiane Amanpour that did not fare quite as well, if only because anchorwomen don’t have the same zazzy appeal as girls with guitars (and did not inspire so many Boomer women to spark a joint and relisten to Tapestry while home alone).

Several factors seem to have driven Weller to the Fisher story: her sustained interest in how women born in the 1950s have navigated their lives, her Vanity Fair reporting chops and fearlessness when it comes to cold-calling celebrities and asking for their secrets, and, most important, timing. When Carrie Fisher died in 2016, a day before Reynolds died, it became crucial to tell the story of her life and examine her complex relationship with her mother. Fisher was only sixty years old, and it was just a few weeks before Trump’s inauguration. She was widely and loudly mourned as a kind of lost voice of female reason when women needed it most, as preparations for the Women’s March were underway. Fisher’s spirit flowed through that week of protest: her righteous anger at the patriarchal establishment, her giving-zero-fucks attitude toward aging, and her zeal for standing up against abusers in the industry.

According to one possibly apocryphal story making the rounds in the wake of #MeToo, Fisher once sent a severed cow tongue from Jerry’s Famous Deli in a Tiffany box to a producer who propositioned a friend of hers, along with a note that read, “The next delivery will be something of yours in a much smaller box.” After reading A Life on the Edge, I fully believe that this happened. Weller’s book is full of wicked, exuberant details like this one—the author is much more concerned with Fisher’s private antics in the service of her friends than her public displays in service of her fame.

Weller does an excellent job of placing Fisher’s life in context, showing that while she may have shifted the culture (and certainly, when she stepped into that terribly uncomfortable gold bikini, she indelibly changed fandom and what it meant to be a mega-star), the culture also shifted her. As her diaries show, Fisher had always wanted to write, but it took seeing the women around her—like her friend the writer and director Penny Marshall, whom she met in the 1970s and was close to for the rest of her life—accomplish their multi-hyphenate ambitions before she felt confident about doing so. And even then, she had many dark nights of the soul.

Life on the Edge is a book about contrasts, about being famous but insecure, privileged but lonely, a love addict drawn to unavailable hearts, a creative force and an industry mentor who was often debilitatingly depressed. Weller interviewed hundreds of people, but the book does not feel overstuffed. Instead, it reads like a great, extra-long magazine profile, full of scuttlebutt and glamour and insight. In a way, the biography’s bouncy tone is a tribute to Fisher’s memory; she knew how to laugh, even when circumstances were dire. She would want her life story to go down like good chocolate, rich and sweet. But she would have also wanted a bitter edge to it, and that’s here too: Weller doesn’t gloss over Fisher’s struggles, heartbreaks, indulgences, or petty squabbles. She shows us a woman who, in her decades-long battles with insecurity, depression, and addiction, often ended up hurting others as well as herself.

As Weller writes, Fisher “was born into a fantasy world, with a brain and a sensibility that found comfort there, and she fought her way to reality.” She became cosmically famous as a space princess, and accepted fame as a birthright, candidly offering her life to the public on the page and on-screen. In doing so, she gave her audience a great gift: As a child of the back lot, she saw a side of Hollywood that few people will ever see, and burst through the facade, telling us how ugly things could get behind the curtain. She knew, like her friend Nora Ephron, who worked with Fisher on When Harry Met Sally, that everything in her life was copy, even her stomach pumping. And it was good copy—the kind only Fisher could have written.

Rachel Syme lives in New York City. She is a regular contributor to Bookforum and writes the “On and Off the Avenue” fashion column for the New Yorker.