FORMIDABLE HARDWICK! Most writers are soon forgotten after their deaths. Yet Elizabeth Hardwick, since her death in 2007, has achieved a rare transfiguration. Having left behind the indignities of mortal life—hangovers, rashes, insomnia, unwritten lectures, misplaced hearing aids—she has been enshrined as an intellectual totem. Publishers have brought out not just a Collected Essays, as one might expect, but an Uncollected Essays, foraging through back issues of Mademoiselle and House & Garden for every glittering fragment. Other literary productions have whetted, not sated, the readerly appetite for all things Hardwickian. The Dolphin Letters, published in 2019, assembled, among other material, correspondence between Hardwick and her husband, the poet Robert Lowell, chronicling their separation. A biography, by Cathy Curtis, brought out last year, seems destined to be the first of several. Hardwick is rapidly becoming established as a classic, to be placed on the shelf next to Hazlitt. (Not, God forbid, next to Lillian Hellman, who after receiving a bad review apparently instructed her friends to “cut” Hardwick on the street.)

The resurgence of interest in Hardwick might seem surprising. This learned critic, most at home in classic British and American literature, whose intricate essays assume familiarity with a literary canon that now goes largely unread: It is she who is so lauded? A simple explanation may suffice: the culture wants what it lacks. For proof, look at the husband. Lowell, worshipped as a genius in his own lifetime for his confessional art, seems less remarkable now in a culture where unmodulated self-baring has become a standard literary strategy.

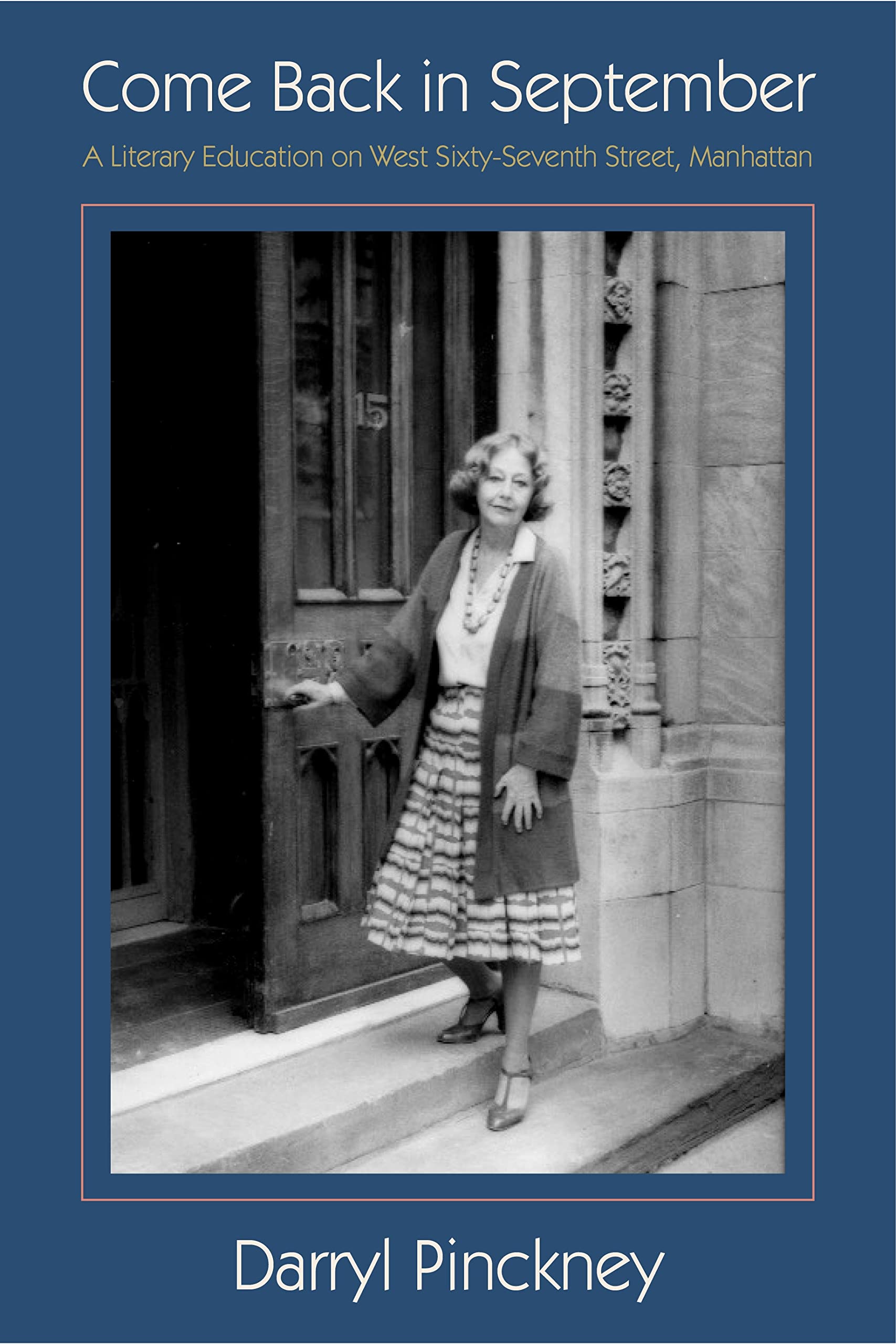

Into the breach tumbles Darryl Pinckney, whose memoir Come Back in September is the latest contribution to the Hardwick revival. Pinckney’s narrative is, in its outlines, the classic literary coming-of-age story. A young man arrives in New York, hoping to become a writer. Literature is his religion, and he finds, on the narrow island, a city populated by demigods, authors whose words he has chanted and memorized, as if Manhattan were a debased Olympus. He sees that the world of ideas is wider and deeper than he knew. He reads, he writes, he drinks all night.

He learns that the republic of letters is a coterie, a “scene.” To enter this closed society, he will need a guide. So, he finds a mentor, a Kentucky-born woman with a regal drawl and fluttering hands and eyes like “blue gas flame.” Who else but Hardwick? She is the great central sun around which everything in this book revolves.

The years Pinckney conjures up, the 1970s and early ’80s, cover the most significant period of Hardwick’s career. The story begins in 1973, when young Pinckney meets “Professor Hardwick” as a student in her creative-writing class at Barnard. A year later, she publishes Seduction and Betrayal, on women in literature, widely considered her finest work of criticism; her virtuosic novel Sleepless Nights followed not long after, in 1979. In between these two pinnacles of prose there occurred much private sorrow. Her decades-long entanglement with Lowell ended in 1977, when he arrived dead at her Upper West Side apartment, having suffered a heart attack in the taxi on the way from the airport.

Pinckney records these events, and many others from this key phase in Hardwick’s life, in intimate detail. By recalling snatches of conversation, books read and sentences written, paths taken through the streets of Manhattan (from College Walk to Broadway down to the apartment on West Sixty-Seventh Street, where the blue-eyed sage sipped Bordeaux on her red sofa), Pinckney conveys a sense of daily life in this now-vanished literary world. But his book is emphatically not a biography. He makes this clear early, when he dandyishly declines to check a fact: “I could maybe find out from Ian Hamilton’s biography of Lowell . . . if I got up from this chair and went in search of it.” As if plucking a book from the shelf entailed greater exertion than writing the sentences we are reading! The point is the refusal to abide by the protocols of biography, the preference for memory over exact scholarship.

Hardwick would likely approve. She frequently bemoaned the banality of biography, a “scrofulous cottage industry” guilty of churning out bloated studies in pedestrian prose, whose practitioners, lacking in style or vision, fetishized the raw material of the archive like diggers in “previously looted pharaonic tombs.” Her favorite life studies were jagged and idiosyncratic: De Quincey on the Lake Poets, Henry James on Hawthorne. “The ‘inaccurate and incomplete’ memoirs so many scholars spend a lifetime irritably, nervously correcting,” she pronounced, “are among the treasures of our culture.” In like spirit, Pinckney has given us an introspective character study, freewheeling and impressionistic, in which he plays Boswell to Hardwick’s Johnson.

Boswell was, incidentally, one of Hardwick’s touchstones. Although she thought that his life of Johnson was a “miracle,” she expressed moral skepticism about his method of composition. There was something unsavory about besotted Bozzy inserting himself into literary history by grasping the great man’s coattails. “Dr. Johnson is treasured,” she remarked, “but odium attaches to his giddy memorialist.” Pinckney, who quotes this line, seems aware of the risk. After he accidently burns down his apartment on the Upper West Side, his journals damaged in the blaze, Hardwick comments tartly: “A happy event. Probably everything I ever said.” Pinckney nonetheless musters a wealth of material, whether retrieved from memory or deciphered from the charred remains. The book is filled with choice quotations from the lapidary lady of letters. On drinking: “Don’t get drunk unless you have a good reason.” On writing: “My first drafts always read as if they had been written by a chicken.” On Pinckney, her “dear little protégé”: “You came to New York to be what you are. . . . A mad black queen.”

Despite its atmosphere of nostalgia, Come Back in September marks a certain maturation for Pinckney. It is an assured handling of themes and techniques he has been working with across his career. He revisits the phase of life explored in his quasi-autobiographical novels High Cotton (1992) and Black Deutschland (2016). Both of these narratives follow a young, artistic Black man casting around aimlessly—in New York and Paris in High Cotton; in West Berlin, just before the fall of the Wall, in Black Deutschland—halfheartedly attempting to make his way in a world that cares more about his dark skin than his meticulously cultivated interiority. These novels contain some cameo appearances from literary celebrities that now seem newly suggestive. Pinckney’s icons of intellectual authority are often women. In High Cotton, his protagonist works as a handyman for an aged Djuna Barnes, frail and cantankerous in her Greenwich Village apartment. In Black Deutschland, his hero meets Susan Sontag in a Berlin record store. Pinckney’s sympathy for feminine genius, richly elaborated in this memoir, runs through his work like a golden thread.

Pinckney has always been formally ambitious. His fiction can be cryptic. Fastidious at the level of the sentence, his novels seem to resist any larger design. They drift and meander from one intense, compressed scene to the next, plunging into memory at will: literature as montage. Black Deutschland, whose hero-in-exile devotes himself to “soulful walks” through Berlin’s streets and passageways, toggles disorientingly between Berlin and Chicago, present and past, as if the novel itself is engaged in a kind of metaphysical flânerie. In Come Back in September, this formal looseness feels appropriate. Pinckney’s roving style, his impressionist blurring, elevates a society memoir into a kaleidoscopic portrait of 1970s New York. The cast of characters is large. His habitual technique of surrounding a passive, observant hero with a gallery of vibrant character-portraits is deployed to fine effect. Jim Jarmusch, Stanley Crouch, and Nan Goldin are just a few of the figures who flit through this amiably populated memoir. Pinckney’s chronological maneuvering, assisted by hundreds of digressive parentheticals in which he reflects on youth from the vantage point of experience, makes this work a poignant study of memory in action.

What does Pinckney remember? He remembers a literary world ruled by two forces: poetry and gossip. This is, unmistakably, a community in which poetry is held in higher regard than it is now. Hardwick and her circle revere poets, commit poetry to heart, recite poems aloud, quote lines in conversation, and read poetry before writing a line of prose. (Yes, Hardwick knew many of the great postwar poets personally, through Lowell. But poetry saturated the literary environment in other ways: the New York School was giving readings downtown, and the modernists remained in living memory.) For the writers in young Pinckney’s orbit—many of them affiliated with the New York Review of Books—reviews and essays, rather than sonnets or haiku, are the circulating currency of the realm. But poetry is exalted as a template. “Write criticism as carefully as you would poetry,” Hardwick advises. A blow, then, when she tells Pinckney, after reading his apparently wretched stanzas, that he mustn’t write poetry anymore.

Second only to poetry is gossip, which this coterie embraces with a marked frankness and intensity. Sitting on the red sofa with Hardwick and New York Review coeditor Barbara Epstein, Pinckney takes in a stream of denunciation, praise, complaint, judgment, and psychological speculation. Reputation and charisma are the main goods in this literary economy, and in the flow of remarks Pinckney discerns who is up and who is down. Hardwick on gossip: “Gossip is just analysis of the absent person, Barbara and I always say. Then we let the absent person have it.”

There is a deep affinity between gossip and literature, as any page of Jane Austen will show. The swapping of stories, the interpretation of character, the epigrammatic put-down, the delicious, revealing detail: no wonder writers relish it. Pinckney weaves a tapestry of gossip, filled with smatter and chatter. Charismatic Sontag is a frequent target. “The new year began with violent denunciations of Susan Sontag,” he writes. An editor describes the first draft of a Sontag essay as a “big blob of snot”; Hardwick offers that Sontag has “no ear.” At a reading at the 92nd Street Y, Pinckney observes ungenerously, Sontag’s black trousers make “her rear seem enormous.” She is spotted dancing with Fran Lebowitz at a bar called the Cock Ring.

Other literary luminaries take punches, too. At James Baldwin’s funeral service, Toni Morrison speaks “mostly about herself.” Mary McCarthy’s work in progress is “appalling.” “You’d think Mary had never read Sartre’s Les mots or even Simone de Beauvoir,” Hardwick says, aghast. Not even the children are spared. Back in Boston, Hardwick reveals, Adrienne Rich’s young sons would hit Hardwick’s daughter while the children played together in the park—the poet-mother’s denunciations of the patriarchy be damned.

Pinckney escorts us into a gay bar and picks up fragments of talk with his roving microphone: “No one reads the Eclogues but queers.” “Sylvia Miles would go to the opening of a refrigerator.” “Somerset Maugham fucked me from behind.”

His story ends before the AIDS epidemic really begins: “It was the last summer before we believed in the plague.” This book captures a world, then, that is irrevocably lost. This urban artistic subculture was devastated. Many of the young men we meet in these pages, full of promise and vitality, would soon perish. In dozens of parentheticals (“he died of AIDS . . . he died of AIDS . . . he died of AIDS . . .”), Pinckney pays tribute to the dead.

His queerness does not shield Hardwick from vicious speculation about what “this old white Southern woman” is doing “with a black boy in his twenties.” “She had position and I none,” he recalls. “Yet the vulnerability was hers, not mine.” He becomes acquainted with Hardwick’s vulnerabilities in other ways, too: her medical worries, her drinking, her sorrow over Lowell. He resembles a character in a Henry James story who, upon befriending an older writer, finds that the revered idol needs protection—that the task of art is, in short, precarious, and the literary lion secretly nurses a wounded paw.

Yet maybe the vulnerabilities were Pinckney’s after all. Hardwick warns him against “imitating her, which, she could assure me, was a dead end.” She cautions him against being too “literary.” “I think the worst thing that ever happened to you was meeting me,” she laughs. Writers learn by imitating. Emulation is a well-tested path to invention. But charismatic influence can corrupt originality. Pinckney seems to wonder, in these passages, if he has lingered too much in Hardwick’s shadow.

In Come Back in September, Pinckney transforms mentor into muse. It is a loving portrait, but not a hagiographic one. He quotes Hardwick saying, for example, that she wouldn’t want her daughter to marry a Black man (“because of the problems the children would have”), and that “white women with black men were inferior Desdemona types and black men with white women weren’t serious.”

Hardwick was known for her brilliant conversation and her rich, fluid, drawling voice. But here she comes alive most dazzlingly in moments of silence. She loved the image, in De Quincey’s book on the Lake Poets, of Wordsworth at tea, cutting open the pages of a book with a greasy butter knife. Pinckney, like De Quincey, has a fine eye for gesture. He shows us Hardwick throwing herself back in her chair after reading a line from Pasternak, “light brownish layers of hair answering”; shaking her head, doubtful, as she spoons juice over a baking dish; fiddling with her amber necklace; placing her feet, clad in suede heels with rhinestone butterflies on the toes, up on the coffee table; lifting her goblet of vodka to hold forth about “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” In these expressive movements we feel the thrust of a personality that is active, embodied, not yet frozen into crystalline prose.

In the Hardwick era, poetry and gossip are inseparable. Pinckney’s memoir offers us a poetics of gossip: the artful arrangement of intimate detail. His aim is, in Hardwick’s words, “analysis of the absent person.” And he provides, in the memoir’s final section, an oblique reply to The Dolphin, the book-length poem into which Lowell inserted, and altered, Hardwick’s pained letters. Pinckney, too, inserts letters from Hardwick, written from across the Atlantic. Like Lowell, he mines her words for material. This old method of betrayal is transformed, made benign, as if Pinckney is trying to repair the old injury, ease the sting of a wound inflicted long ago.

Perhaps it is the secret dream of every devoted reader to pass into literature, to become one with the printed words on the page. Through the force of her reading, Hardwick achieved this, winning a posthumous existence as both author and character. She elected to play an unusual and difficult role: the critic as artist. Pinckney’s portrait asks us to share his admiration for a writer who saw the essay, even the book review, not as a disposable form of journalism but as an opportunity for literary creation.

Charlie Tyson is a Ph.D. candidate in English at Harvard. His writing has appeared in the New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Baffler, and other publications.