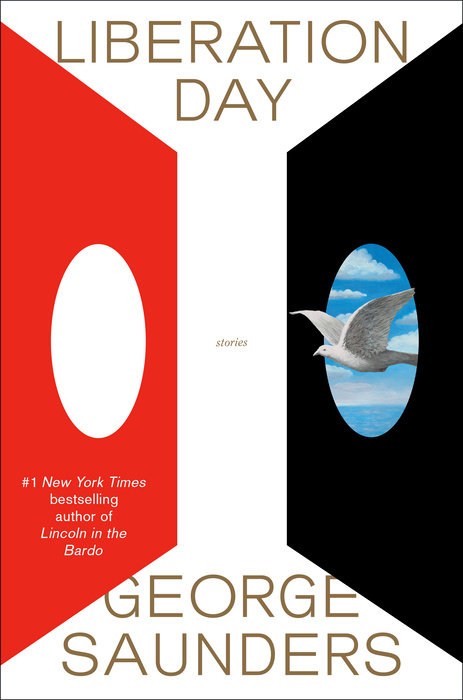

ANGELO HERNANDEZ-SIAS: A funny story about the title story of Liberation Day (Random House, $28) is that you woke up one night from a dream and wrote something on your notepad, thinking it was the most brilliant idea. And when you woke up, you found it said: “Custer in the Bardo.”

GEORGE SAUNDERS: In the dream state, it was so perfect, it seemed like a big advance over Lincoln in the Bardo. Luckily, in the light of day, I thought better of it. I had been wanting to write about Custer for a long time, but after that dream and the horror of reading that title in the morning, I just gave up on it. And then, about halfway through writing what became “Liberation Day,” this kind of sci-fi story, I needed some sort of shtick—a vignette for the character to narrate. And I thought, Oh, what the hell? I know a lot about Custer, so let’s just drop it in there and see if the rest of the story forms around it. I talk about this a lot in my workshop classes—writing has just got to be fun. And if it’s not fun, it won’t ever mean anything. If we’re having fun, there’s a greater chance that we’ll write ourselves out of our plan, into something new—new and even confusing. This is a good thing.

Sometimes plot is just recognizing your own discontent as a writer at a certain point in a story. Saying, “Gosh, this story isn’t holding together,” or “This story is feeling boring to me,” or “This question is stopping me from moving ahead.” If you just let the story turn to that discontent, that’s what we call plot. It’s the story responding to the story.

And as the reader it’s satisfying to see that boredom mirrored, or that question addressed.

Right, it’s like I’m going through a doorway and the reader’s coming through a second later. The writer has a certain experience, and the reader, theoretically following pretty closely behind the writer, has a simulation of the same experience.

You say you’ve had a long-standing interest in Custer. Does that interest extend to history more generally?

Yes, nineteenth-century history is really alive for me. It might just be that I’m a reincarnated dead infantryman. But also, it’s a time far enough back that nobody really knows how things were. We don’t know how houses smelled or how people actually spoke or what their mind cloud would have felt like to them. So that gives the writer a lot of leeway. At the same time, we can sort of picture Custer, we can picture Gettysburg. Also, when I was here at Syracuse nine million years ago, this professor used to call me Custer. I had a big mullet. I was kind of out of my league and I just loved that he even noticed me. So, I read that Evan S. Connell book, Son of the Morning Star. There was just something so epic about that battle, so tragic—quick death in the summer heat.

What prevents you from writing an actual history? I would guess that part of your answer will be that there’s more obligation to—actually, no, let me not assume your answer.

You’re right about that, there’s a lot more obligation to what actually happened, or in this case what may have actually happened, since nobody really knows. That obligation kind of negates the thin little gift that I have, which has more to do with invention, I guess. I could be a moderately OK historian, but why? It’s like that Flannery O’Connor quote: “The writer can choose what he writes about but he cannot choose what he is able to make live.”

You’ve talked about how oftentimes when you’re working with a realist conceit, the interior monologue goes haywire. But there are stories in this collection, like “Sparrow” and “A Thing at Work,” that seem to be realist through and through. What’s your approach like then?

In order to get the language to pop, I have a few different ways I can go. There’s the “Liberation Day” approach, where there are no limits. And then there’s a story like “Mother’s Day,” where you’ve got intense inner monologues that you can have a lot of fun with. And when I got to “Sparrow,” I could tell there weren’t going to be any internal monologues, and it’s not really sci-fi. Around that time, I had read some Gertrude Stein. And that is like, strong medicine. She had this way of boring down on a thought by shaped repetitions, and I found myself doing something like that. “Sparrow” started when I woke from a dream and just wrote down the first five or six lines, which, to me, felt sort of like Stein. I felt myself asking, How can I describe these ostensibly realistic events in a more interesting language?

“Sparrow” is a love story about two characters named Randy and Gloria, who work together. Gloria is presented as a completely unremarkable person and Randy is an egoist. You write, “He liked the way she noticed and enjoyed the way he tended to get most things right.”

He’s a dude. Definitely.

Where do you think the humor of this story comes from?

Well, for that part you mention above, we’re in Randy’s head. And he’s trying to earnestly describe what’s going on as he develops this crush. But in the process, he’s sort of showing his ass because he’s thinking, you know, I really like her because she agrees with me, and since she agrees with me, she’s very bright! At first, I was just trying to be funny. But then I found something else going on. Gloria is, at least according to this story, a really dull, flawed, unlovable woman, who falls in love with the guy who the story tells us is an egotistical guy. We’ve got a love story between two people whom we’ve been told, one, we shouldn’t like, and two, won’t like each other. But they do anyway. And isn’t that kind of every relationship? Two odd people, finding comfort in one another? So part of the trajectory of that story was me thinking, Hey, I’m actually not making fun of anybody. I’m describing a great love affair, maybe!

Language is at the heart of the conceits of “Liberation Day” and “Elliott Spencer” in particular. In “Elliott Spencer,” the main character has been inducted into a cause that he’s not fully aware of, and he’s basically been programmed to say a few keywords. Like Jeremy of “Liberation Day,” he has no memory of his previous existence. When you think of a sci-fi conceit, what draws you back to language itself?

Usually, it starts with the language. Before there’s any conceit, I’ll have a page or two of some language that I’ve either accidentally arrived at or that has come from a little thought experiment.

One of my early misunderstandings of Buddhism was that you’re trying to have zero thoughts. That’s not actually true, but it got me to wonder what it would be like if you eliminated all thought—if you took all the data out and left the operating system intact. How would a mind refill with language? So, with “Elliott Spencer” I was goofing around with that idea and stumbled on a tone I liked. And then my mind was just going, All right, so who is that talking? And how did he get in that state? And again, that’s another way of generating plot. If I do a weird voice, the reader’s natural question is, Why is this guy talking so weird? And you have to discover the answer as you’re doing it. You make the funny voice first, and then the rest will take care of itself. That’s essentially what we call “world-building”—making a case for the weird voice.

You recently wrote an introduction to Dubliners, and noted how the arc of the collection bends towards disillusionment. What’s the arc of Liberation Day?

Yeah, I think Joyce himself said that the collection progresses from childhood to youth to adulthood to public life. And the trajectory, in my interpretation, is one of increasing compromise and burden. In each of the stories in Liberation Day, someone starts out deluded and confused and misled, then sheds that delusion and moves in the direction of truth, with different results. But this pattern doesn’t interest me abstractly—I just found myself arriving there. When I’m writing a story, I’m just trying to be lively for nine pages, and then refine that liveliness so the story corners more sharply. What’s interesting is that the subconscious still brings you somewhere.

I’m glad you bring up the subconscious—I was hoping to ask about its role in your process.

I feel like the handmaiden of the subconscious. I’m just there to receive whatever it feels like sending. I don’t really know how it works, but I know it’s real—that “craft” is an individual writer figuring out a way to get clear access to her subconscious mind. I trust in that process more and more as I get older. I know that my way of opening that portal is revising by taste, on a very micro level, over and over. The thrilling thing is being in the presence of something smarter than yourself, something you can access by mundane technical means.

Have you ever abandoned a story?

I always say I never do that, but I did recently. There was one story in the manuscript, called “Appeasement, Ohio.” It was a very political story about a working-class family with a right-winger son who is part of a group that claims the American Civil War never happened, that it was a liberal plot. It’s pretty funny and has some good moments, but everyone I showed it to was like, “Nope.” It could be that I go back to it and at least find something to pull out of it, or it’ll make more sense as to why it wasn’t working.

Yeah, maybe it’ll be in your next collection. It’s fascinating to hear about the mess and chaos and persistence that the work requires.

Yes. It’s interesting that as you get older, as a writer, you have to keep trying to find new ways to mystify yourself. New approaches, new forms. And in this way, writing is a real lifelong gift. It would be scary to come to the end of feeling the mystery in life, and art is a way of infusing your days with a relation to mystery. And it’s lovely to feel that the problems of life are still speaking to you, through your form.

And it sounds like there might even be a kind of inevitability to how these questions arise for you. You’re playing with the raw materials of language, and then before you know it, the structure that you’ve built is asking some philosophical question.

That’s a beautiful way to put it.

It’s a reassuring thought, that the work will take care of itself.

Your mind will create the problems and create the solutions and then that process will create a whole second set of problems that you can then move into.

Angelo Hernandez-Sias is an MFA candidate in fiction at Syracuse University. His writing has appeared in n+1 and Socrates on the Beach.