I WAS SEVENTEEN AND IN MY THIRD YEAR OF FRENCH when I learned the phrase la petite mort: “the little death.” The boy in class I had a crush on—what was it he called himself? Roland, Jean-Pierre, Henri?—informed me, whispering so Madame Chrétien wouldn’t overhear us, that it was meant to describe an orgasm, or rather (I discovered later, after experiencing more than the panicked fumbling of high school trysts), the untenanted feeling that comes after having had one. Of course, I thought, of course, great sex would be something like an annihilation of the self. In my diary, I wrote of my ache for Roland-Jean-Paul-Henri that “I am already in the process of dissolving,” that, in proximity to him, the borders of my being no longer seemed to be my own. I felt sure that the little death, when it arrived, would shepherd me to a big love or, better, to a world that radically exceeded the threadbare parameters of my own.

Lately, I’ve been digitizing my diaries, which is how I’ve dredged up this forgotten history. My recollection of that boy and my crush, as well as the affinity between desire and ontological disintegration, uncannily echoed a passage I happened upon in the diaries of the French author Annie Ernaux last summer. Embroiled in an abject affair with a married Soviet diplomat, Ernaux confesses that cumming with him seemed a kind of dissolution: “I’m still inside his skin, his male gestures . . . caught between fusion and the return to self.” Passion is often a project of effacement, an interpenetration of self and other that threatens the unity and sovereignty of the individual subject.

Orgasm itself, though, proves a malleable condition across Ernaux’s corpus, the place where her ongoing projects of self-making and writing become knotted together (she has termed this a “total novel” of life). In Shame—her 1998 account of witnessing, as a child, her father’s attempted murder of her mother—she binds the memory of domestic trauma to her first climax, a seemingly incongruous association until you consider that, for the women of Ernaux’s generation, “Nothing . . . mattered as much as a girl’s sexual reputation,” and the onset of menses signaled a new and “deadly time” when women’s freedom became suddenly “ruled by blood.” Sexual shame was more than a bad affect: it was the totalizing determinant of a woman’s existential value. In that passage, importantly, Ernaux’s initial masturbatory orgasm is not a dispersal but a consolidation of self, the “moment when [her] sense of identity and coherence is at its highest,” a kind of personal spiritual communion. Elsewhere, the aftermath of orgasm manifests as a “fatigue,” a world with no “outside,” an indeterminate and “hollow place.”

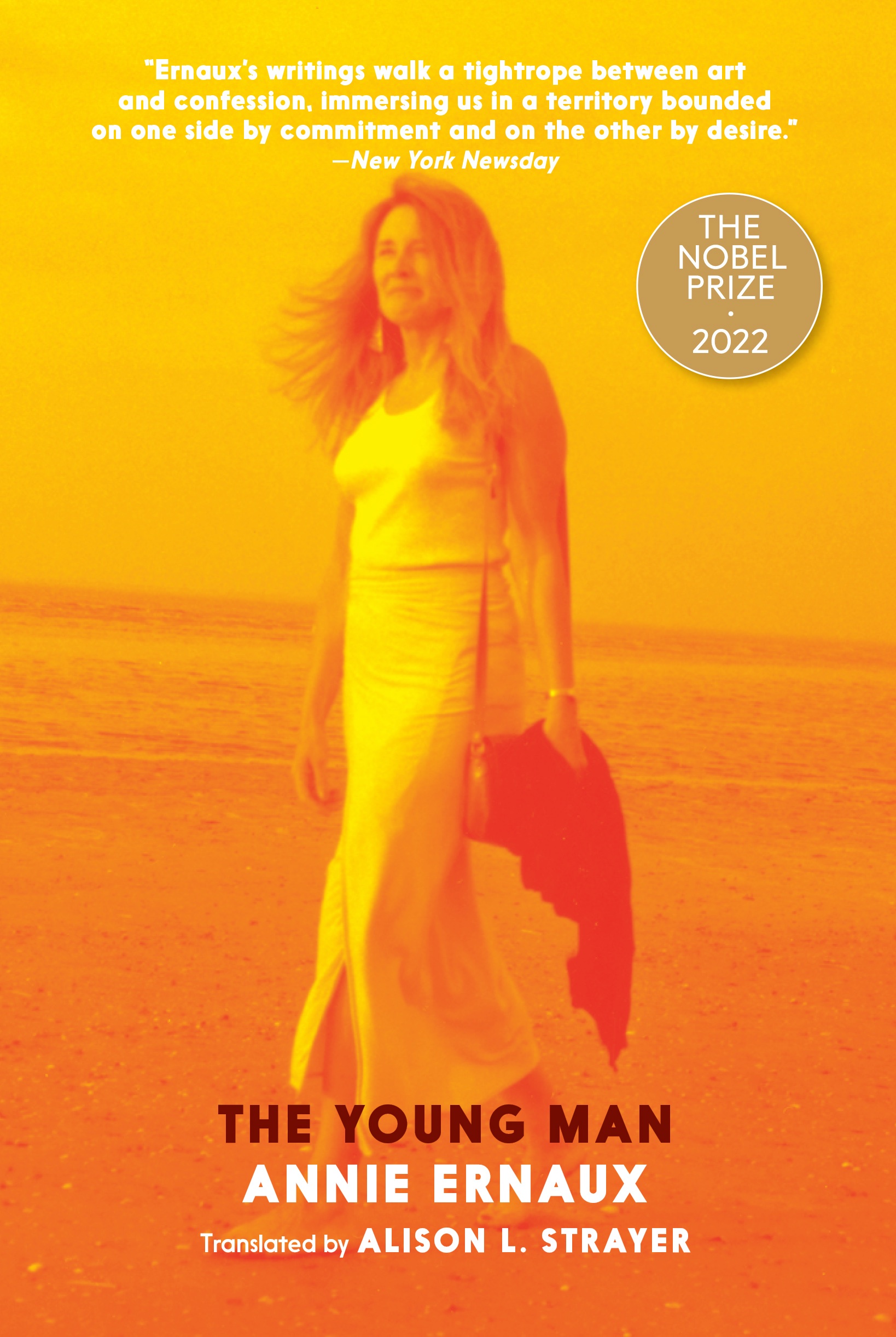

For decades, Ernaux has traced an umbilicus between sexual release and the act of writing. Beginning with 1991’s Simple Passion and continuing through Getting Lost (2001) and The Possession (2008), the author has meticulously dissected the ways sexual and aesthetic creation summon experiential elsewheres in which we become provisionally absented from time. (These states are also for her companions to death—time’s inverse.) An orgasm opens The Young Man, Ernaux’s latest, where it is a kind of “dereliction” that functions, unanticipatedly, as a utilitarian tactic—an antidote to a period of writer’s block. “Often I have made love to force myself to write,” she tells us, suggesting the erotic act is akin to the blank page, interzones interrupted by the violent rupture of climax—or else a first sentence. Even compared to the ekstasis of sexual harmony, there is “no greater pleasure,” she insists, “than writing a book.” At fifty-four, then, she embarks on an affair with a man thirty years her junior, a university student she’d corresponded with, to “spark” a new text. Though he’s living with a girlfriend in Rouen, he soon breaks things off and the entanglement with Ernaux “became a relationship that we longed to take to the limit.” A romance on its face, The Young Man gathers singularity and texture as an account of manifold transits: between youth and age, living and dying, in and out of passion, passing through menopause, and from Ernaux’s impoverished beginnings through her ascension into the literary bourgeoisie.

Ernaux is a superlative archivist of heterosexual pleasure—one of the last living straight girl icons—a habitual “initiatrix,” a self-professed connoisseur of cum. It’s worth repeating that Ernaux’s notorious “crudeness”—for a time following the star-making book, Simple Passion, French weeklies mocked her as “Madame Ovary”—is a politically insurgent act, a renunciation of sexual shame as a disciplinary apparatus disproportionately weaponized against women. Her attention to the baroque possibilities of the body moreover distances her experience from women’s orthodox social roles. Following the breakup of her marriage to Philippe Ernaux (one of the few experiences she hasn’t ruthlessly anatomized in her texts), Annie has tirelessly guarded her freedom from the domesticating ministrations of romance. She is, finally, a lover, not a live-in. She begins, however, spending weekends at the young man’s apartment, reminded of the improvident delights of fucking a man who keeps his mattress on the floor, returned to the city of her student days—a city, she realizes, that for years she’d only driven through en route to her parents’ graves in Yvetot, the Normandy commune where she’d been raised.

The affair transports Ernaux to that past. In the young man’s economic “destitution,” she sees, again, her working-class origins. His “gestures and reflexes were dictated by a continual, inherited lack of money,” reassembling the “hickish” boys of her youth. “He embodied the memory,” she reflects, “of my first world.” Annie Duchesne (as she was then known) had been the daughter of shopkeepers, situated, as she remarked in her Nobel lecture last October, among “people despised for their manners, their accent, their lack of education.” Unlike the constituents of that forgotten class, the young man is a layabout, living dislocatedly on the future promises of luck—“work for him meant nothing more than a constraint with which he did not wish to comply.” Ernaux escaped her upbringing through academic achievement and forged an autonomous path after marriage and motherhood by teaching and writing. For her, “a profession had been, and remained, the condition of my freedom.” Like the women of her childhood, she did not have the luxury of principled abstention from the workforce. And as a woman who came of age in an era when “contraception was prohibited and termination of pregnancy a crime,” she has shown time and again how weathering class precarity and the structural indignities of misogyny are interconnected struggles. But with the young man, she concedes, she is “a bourge.” She must admit to the vast distance between Annie Ernaux, class defector, and the girl she once was, a girl, as she writes in The Years, who’d “lived in close proximity to shit.”

If he conjures her past, the young man likewise situates Ernaux in an ineradicable future—the terminus of mortality that awaits us all. Though he at moments renders her “ageless,” he also “was my death, as were my sons for me, and as I had been for my mother.” She is adamant that, without fear of social stigma, men her age have been reveling in the revivifications of May-December dalliances for ages and so, “I saw no reason to deprive myself.” And yet the particular amusements of the individual cannot themselves retool the system; she remains subject to the erotic politics of a world that exiles aging female bodies from the libidinal economy. Inside a sexual imaginary engineered by and for straight men, the idea that an older woman could relate sensually, rather than maternally, to a younger man is strange, if not outright abhorrent. As Ernaux recognizes, what people see when looking at her and the young man is, “in some tangled way, incest.” The couple does little to dispel the fog of this taboo. She takes him to see the Eugène Ionesco play The Bald Soprano, a “ritual [she’d] observed with each of [her] sons when they entered adolescence,” oddly recapitulating their familial bildung. He, meanwhile, calls her le reum—Verlan slang for mere, or “mother.”

As their affair loses steam, the young man unnervingly confides in her that “I would like to be inside you and come out of you so I could be like you.” His is a chaos of longing: to penetrate, be born of, and finally resemble or even replace Ernaux (“he was my death”). This omnidirectional desire disturbs every kind of temporal and ontological order. His yearning to have a child with her is, in fact, what sows rot in the ground of their mutual fantasy, the utterance that precipitates the end of the affair. Ominously, his apartment window overlooks the Hôtel-Dieu, the hospital where a hemorrhaging Ernaux had been treated following complications from a “backstreet” abortion she’d had in the 1960s. (She documented this event in her first novel, Cleaned Out, as well as in 2000’s Happening.) The building, decommissioned and under construction, was “illuminated . . . throughout the night,” returning her to that rift of trauma—invoking, suddenly, the moment when “Kennedy had just been assassinated,” when a man not much older than this one had impregnated her, when a popular song on the radio was inseverable for Ernaux from a state of “mad love and dereliction” (that word, “dereliction,” binds her memory of the abortion to the opening orgasm of the text).

She’s come to feel that they were only “reenacting scenes and actions already past . . . as if I were writing/living a novel whose episodes I was constructing with care.” Fascinatingly, Ernaux identifies the young man only as “A.,” an odd doubling of the initial she’d used to anonymize the diplomat-lover of Simple Passion four years previously. As in that affair, the borders between Ernaux’s experience and her documentation of it collapse. In her diaries she at first insists that “I wanted to make this passion a work of art,” before correcting herself to say that “rather this affair became a passion because I wanted it to be a work of art.” She initiates the affair with the young man to “spark” a book, only for the book to consume the affair’s immediacy, its lived reality. Art supersedes—it enfolds—life. She wonders whether all experience henceforth will seem to her a recursivity, whether the “present was only a duplicate of the past.”

Like Proust (whose In Search of Lost Time haunts her erotic writing), Ernaux sees time not as chronological but palimpsestic: in the existing moment, traces of the past remain, nearly illegible but inextricable from it. Thus the past may intercede at any point. In the most recognizable passage from Proust, this is signified by the madeleine, which harbors his philosophy of “involuntary memory,” disentangling fictions of linear progress, rendering time an irrevocably permeable condition of being. In my diary eight years after that French class crush, I wrote of a man I’d been fucking that “I want to melt into him, to have a single body, to have him inside me entirely and forever.” In the time of those men, I had been overcome—seized—by longing. But in transcribing these events with relative consecutiveness, the memories become shorn of singularity, divested of their strange psychic pull. Almost a decade after that first need, could I hear the distant ringing of my previous language? My teenage past hummed beneath the skin of my grad-school heartbreak. “Proust suggests,” Ernaux reminds us in Shame, “that our memory is separate from us, residing in the ocean breeze or the smells of early autumn . . . that recur periodically, confirming the permanence of mankind.” But Proust, crucially, also sees memory as having a kind of alchemical relation to the present—it metamorphoses and reorders us in our recollections. In this sense, the truer descriptor for Proust might be anamnesis, an innate knowledge that lives inside, precedes, and exceeds the particular histories and life span of the individual; a remainder that now and then appears above the waves, a “souvenir” (from the French, “to come from beneath”), something like the “soul” of time.

Ernaux, in turn, intermixes these ensouled sediments with the specters of the personal—her memories, the stuff of one woman’s experience—which “confirm the fragmented nature of my life and the belief that I belong to history.” Though at first the affair with the young man had transported her beyond the limits of age, in the end she sees that, while he’d torn her “away from [her] generation,” she was “not part of his.” His youth cannot resurrect hers or occlude the looming gloam of death. For an instant she considers in-vitro fertilization with the young man, but a book has begun to reveal itself to her: she starts writing the pages that would become Happening, realizing she must leave the young man, terminate, rather than bear him into the world, “as if wanting to tear him away from myself and expel him as I’d done with the embryo.” In a sense, A. gets his wish—though not, perhaps, in the fashion he’d hoped. Ernaux, ever and again the writer, surfaces, having “found that I was happy to be entering the third millennium alone and free.”

Jamie Hood is the author of How to Be a Good Girl (Grieveland, 2020) and a twice-monthly newsletter on Proust, regards, marcel. She’s written for SSENSE, The Nation, The Drift, and other publications.