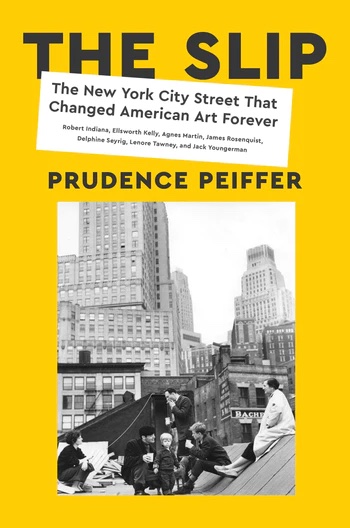

BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist.

“Place is an undervalued determinant in creative output,” writes author-scholar Prudence Peiffer in The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art, her tale of these artists at that time, proposing that any chronicle of an aesthetic evolution should consider not only who but also where. “What if, rather than technique or style, it’s a spirit of place that defines a crucial moment?” This question seems to perfectly befit the twentieth century, the age of the found object, the readymade, the already-made, of Pop art and appropriation, when artists began grabbing whatever was around them—the commonplace, the discarded, the overlooked—and calling it subject matter, using it as material. As Peiffer explains:

To think of an artistic group in terms of place is to write a different history of art, one that can be more inclusive, more open to serendipitous interaction, and can also explain more of the cultural, emotional, and financial context behind any art object.

Such a narrative shift might elicit another question: If place is relocated to the fore of art history rather than relegated to the background, what refreshed literary form might arise?

This is a terrific challenge, and The Slip takes it on, launching with a brief history of the land that would one day be home to these artists: from the earliest humans who paddled canoes up to the lush island of “Manahatta” around 1000 BCE, to the construction of the New Amsterdam settlement’s first pier on the East River in 1648, to the Slip’s role as an active harbor during World War II. By the time Peiffer’s subjects arrived in the mid-1950s, the sailmakers who’d once cut their sails in the wide-open lofts near the water had mostly vacated, leaving behind spaces large enough for artists to live and work, a new and unusual arrangement. If, once upon a time, a studio was a kind of stage—cast with models or laden with fruit and flowers for still lifes—the Slip’s spaces functioned more like cloisters. Cleaning, scraping, and repainting were the artists’ initiation rites, poignant metaphors for their reworking and reimagining of what art could do and be.

The neighborhood had no art-supply store and little in the way of amenities: breakfast at a restaurant called Sloppy Louie’s, a small grocery with a limited selection of goods. But the Slip was a kind of oasis: the center of the art world, then in the thrall of Abstract Expressionism, was up in Greenwich Village, and once the business day was done, the Slip’s bustling streets were dead quiet, aside from the clamor of drunken sailors. Cheap rent afforded these artists the most precious real estate of all: headspace. According to Martin: “When you paint, you don’t have time to get involved with people, everything must fall before work. . . . That’s what’s so wonderful about the Slip—we all respect each other’s need to work.” Martin’s “we” refers to what was perhaps the most significant virtue of the Slip: the community of artists who, living so close by, supported and influenced one another in myriad ways, and Peiffer’s book comes to life in the vibrant details of their connections. Martin, as the de facto “den mother,” was, according to Kelly, “very much a healer,” counseling the younger artists when in crisis. Indiana and Youngerman, needing money, teamed up to teach an art class, which didn’t succeed in part because students didn’t want to go all the way down to lower Manhattan. Kelly and Indiana, lovers for a time, eventually stopped speaking because Kelly disapproved of Indiana’s choice to include words in his work—a choice that would become Indiana’s signature move. And so on.

But the Slip itself supported their burgeoning practices, too, wending its way into the work. “Before Coenties Slip, I was aesthetically at sea,” recalled Indiana, who scavenged the area’s streets for the scrap from demolition sites that would become the materials for his now-iconic wood sculptures. Martin also dabbled in assemblage, making objects out of bottle caps and nails and wood. Each member of the group paid homage to the neighborhood in turn: Youngerman titled a 1959 canvas Coenties Slip; Kelly, a work he made that same year, Slip; Rosenquist, a 1961 painting of a spoon, fork, and egg yolk, Coenties Slip Studio. And so on again.

Throughout the book’s first half or thereabouts, Peiffer advances her premise by weaving historical facts about the Coenties Slip into the artists’ stories, interjections that sometimes weigh down her narratives’ otherwise ascending arcs. The tender recollection of a walk that Indiana and Kelly took together in Jeanette Park in 1957 is incised with a brief report on the ill-fated steamer for which the park was named. The mention of a quote that Indiana borrowed from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick to use on a brochure prompts a several-page chronicle of Slip life in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and how it was irrevocably altered by the appearance of the El train in 1875. And an account of Tawney’s sprawling, light-filled loft space and the illustrious guests she would occasionally host there—composer Harry Partch and author Anaïs Nin among them—is diverted by a discourse on sail-making. These interruptions, though unwieldy, are not wholly uninteresting and are absolutely in line with Peiffer’s conviction that place be properly accounted for in art-historical scholarship. But the real challenge is a literary rather than a scholarly one: How to make location as compelling as character or as dynamic as even the mildest plot point? “Place is a tricky protagonist,” the author concedes, but its resistance to this role, its inherent misbehavior as such, is an obstacle well worth attending to, at least for the ways in which it could reshape history’s telling. In the end, this book, like its subject, provides readers, its temporary lodgers, a solid launchpad from which to imagine how.

As it is, the Slip performs here most convincingly as the artists’ silent interlocutor and coconspirator—a source of free materials and affordable space—and as a metonymy for the fleeting years and figures that compose the whole of this story. Even the artists were aware that whatever sifts into consciousness from the material world ultimately constructs a state of mind: about her fourteen-foot linen and wood sculpture Dark River (1962), Tawney said: “It is an inner landscape that I am doing.” Indiana traced location through his avocation in lines that echo the wordplay of Gertrude Stein’s “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”: “A ‘slip’ is that construction that a ship berths in, you see. It slips into place and docks. . . . The Slip has been an influence and a very formative force in my painting.” Explained Rosenquist, plainly, about his place in the world: “I think of myself as an American artist, growing up in America, thinking about America.”

As is the American way, all but one of the buildings where the artists once lived on the Slip were razed by the ’60s to build office towers. The tenants were evicted or moved out. Seyrig left for Europe in 1960 to film Alain Resnais’s New Wave classic, Last Year at Marienbad (1961), which would make her an international cinema star. Martin relocated a few blocks north to South Street, then departed the city for good in 1967, explaining, “I had established my market so I felt free to leave.” Tawney eventually settled in with the artists who were inhabiting SoHo lofts. In 1963, Kelly moved to the Hotel des Artistes on the Upper West Side, where he took his walks through Central Park rather than by the river. Indiana, the last one standing, stayed until 1965, remembering his former home as a “New York waterfront demolished by Moses, Rockefeller, and Progress.” But of course, Coenties Slip was a place of commerce before Indiana and the others moved in. A street may change art, but art changes a street, too. Then art changes again, and streets, too, and both keep doing so, though now the insatiable and intertwined economies of real estate and the art world—both fed by gentrification, a term that would enter popular conversation around 1964—make it harder to say which happens first.

Jennifer Krasinski is a writer, critic, and contributor to 4Columns, Artforum, and the New Yorker.