MIDWAY THROUGH ABOUT ED, Robert Glück revives a line by Frank O’Hara: “Is the earth as full as life was full, of them?” Referring to three of O’Hara’s recently deceased friends, the line appears in “A Step Away from Them,” where it clangs against the rest of the poem and its meandering attention to noontime activity in midtown Manhattan, 1956. It perplexes Glück, whose About Ed remembers Ed Aulerich-Sugai, a lover and friend who died of AIDS-related complications in 1994. “The misdirection threw me,” Glück writes, “from the earth being full, to life being full, instead of Ed being full of life. Was life still full. . . ? Was it always? Was it ever?”

Glück’s somewhat lyrical question asks after “the fertility of death,” as he calls it elsewhere. That vivid phrase suggests its author’s heterodox approach to a literature of loss, grief, and HIV/AIDS. In his grief, Glück elaborates a particular and surprising structure of feeling: abundance where one might have expected absence. Meditating on Ed’s death and life, Glück makes death abundant in his own thoughts and actions, and works grief richly into his sentences. He orients his grief toward the future, in which direction death also points. Glück’s is a profound thesis, and its stakes become more significant in the political context of mass death—the forty million and more dead of AIDS, which is to say of political neglect and pharma-capital profiteering, and the victims of every other war that the powerful wage on the dispossessed. The work of mourning, the work of dying, and the work of making a meaningful life are here delicately premised on each other.

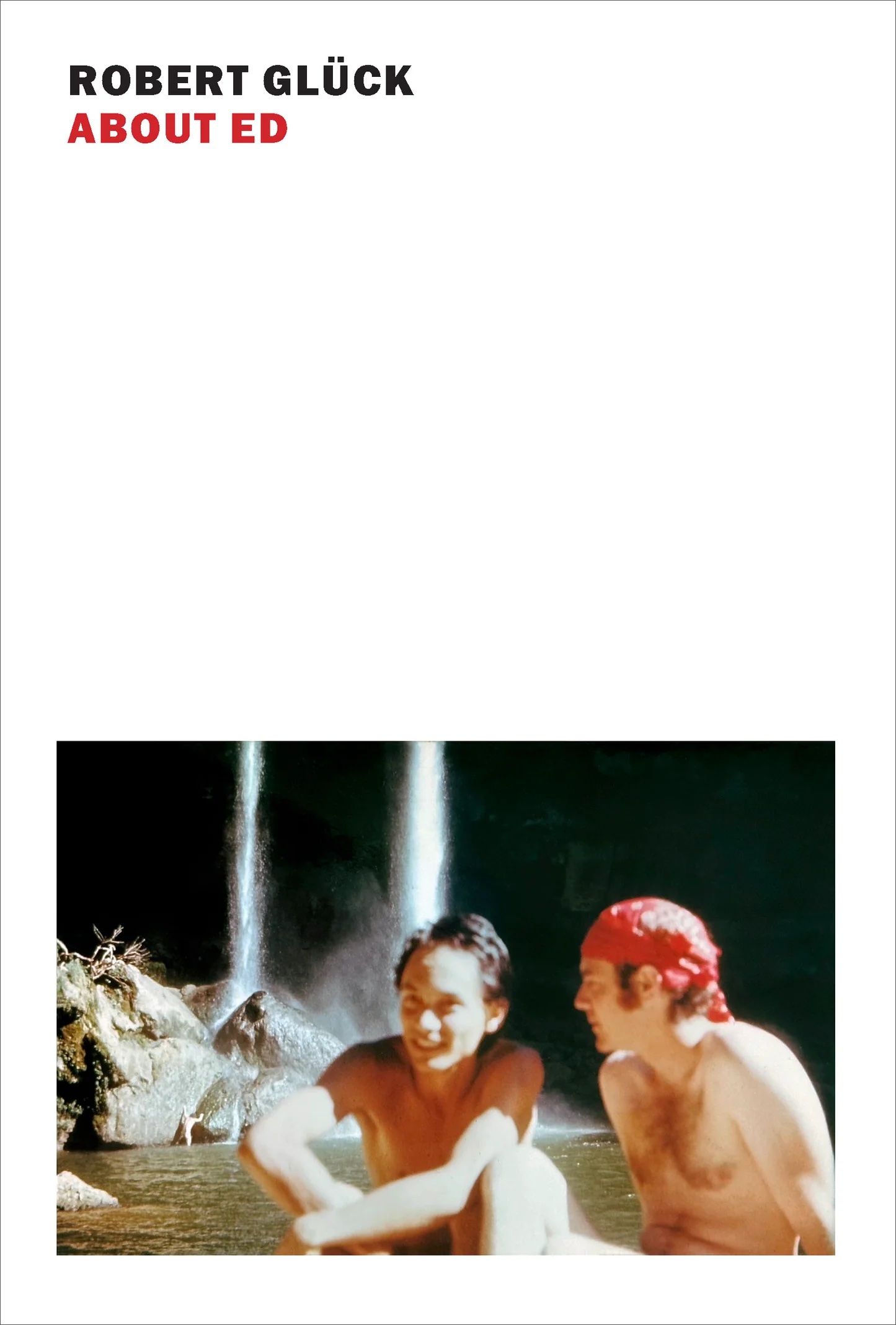

About Ed has been a long time coming. A portrait of Aulerich-Sugai, an AIDS memoir, a “meticulous account of lightning striking,” it took Glück almost two decades to write. It joins a body of work whose shrewdness and dynamic formalism renders its content both startlingly immediate and sublimely abstract—obliterating, as Glück discusses in his recent Paris Review interview with Lucy Ives, the “middle distance” of realist description. In his novels Jack the Modernist (1985) and Margery Kempe (1994), Glück works his fingers into the sinews that connect gay intimacy to the contested transformations of people and place. Like Jack and Margery, Ed provides a meticulous, precise account of a love affair, in Glück’s hands a capacious form for thinking about the movements of history that made even kisses possible. But with new emphasis, About Ed places death at the center of the drama, as in a medieval morality play—the first section is titled “Everyman.”

In a way, Glück’s latest endeavor sets up a critical test for the aesthetic program he developed for New Narrative, the Bay Area artistic movement that he’s most closely associated with, and that’s enjoyed a sizable renaissance since the mid-2010s. In an essay on caricature republished in his collection Communal Nude (2016), Glück cites the text-metatext writing method he developed with fellow New Narrativist Bruce Boone. “The text is the narrative (with its timespan, characters and action), and the metatext is a running analysis, its point of view based on the future, or a real community.”

The point of view based on the future gives Glück’s work—often not explicitly political in its content—a consistent political orientation, in its hot attention to change over time. “Margery lived during the Hundred Years War, the collapse of feudal systems, and the plague,” he writes in Margery Kempe, a novel that bridges the life of Kempe, a fifteenth-century failed saint, with his own. “At the beginning of modernity the world and the otherworld lay in shambles. Margery was an individual in a recognizable nightmare: the twentieth century will also be called a hundred years war.” Glück’s extravagant leap across a five-hundred-year chasm, the period when capital began to shape the lives of most people on the planet, typifies his writing—its breathtaking movement across scales of experience, its continual look backward at the present from the speculative aim of what social life might ultimately be.

In About Ed, the future, the dimension of political possibility, now includes the departed. It has to. It reminds me of the Cosmists in the early years of the Russian Revolution, utopians who believed that socialism must rescue the dead as well as the living. In About Ed, Glück, dizzy with the “futureless mood” of “the Reagan/Bush years,” rediscovers the future in Ed’s tomb. He describes the small exhibition niche in San Francisco’s Columbarium, which Ed, a painter, decorates meticulously. Bob has his doubts about Ed’s selection of long-lasting materials—“After you are dust, is there a difference between two hundred and seven hundred years? Ed doesn’t realize that . . . you are no longer included.” But Glück changes his mind. “I hope you, Reader, will join us in Ed’s small exhibition space, in his work about death and the future,” he writes a hundred pages later—a reversal so steadfast it feels like an epiphanic conversion. So dying here becomes an artistic exhibition, and Ed’s tomb this painter’s most lasting work of art. About Ed transposes this sublime gesture across media, from tomb to book, such that Glück publicly prepares for his own death in an open document that contains Ed, Bob, and an indiscriminate you. In Glück’s sequence of metonymic chain reactions, death grants meaning to the life that came before it, and only an orientation toward the communality of death can restore a future dimension to political life.

Welcoming the reader into Ed’s tomb, Glück also shares his abundant grief. Memories of Ed—his comeliness, his art, his sex life, his attachments, his long fight with AIDS, his variable treatment of Bob as a lover and friend, his delicate manner—fill the first half of the memoir, and then his death arrives, and Ed is gone so abruptly his absence from continuous narration feels like unbearable loss. Is that too familiar a stance, an overidentification? I wept for Ed, and then I felt embarrassed, so I wept for my friends instead. But bereavement itself is an experience of overidentification, mourning the part of oneself that rested in the dead. Drawing on Ed’s journals, Glück regularly writes in persona: Ed dreaming, Ed receiving the news of his serostatus, Ed having sex as an adolescent. Glück’s contribution to the AIDS-memoir genre plays with the deindividuation of grief, in his drag as Ed, in the reader’s as Bob. Glück tosses a ball to the reader—no, not a ball, a bone.

Grief dissolves normal social boundaries. Might they be reconstituted otherwise? In a way, it’s apt for New Narrative writing, which typically breezes past the standards of privacy and property. Its most notorious icons casually defy common norms of authorship—through collaged quotation of other writers’ words, or overeager disclosure of intimate detail, or writing out lovers’ quarrels as if they belonged to the reader, too. In one chapter, “Bisexual Pussy Boy,” it seems as if Glück’s best dead friends, Ed and Kathy Acker, are girltalking in the room with him while he fucks an obnoxiously attractive man in a straight relationship. “I am telling this to Ed and Kathy. . . . My head was tipped back as well in order to read the fine print on Zack’s little butt.” In this sex scene, “Zack’s ass took the place of his head”—Bataille’s acephalous fantasy made flesh. It would be indecent to keep it to oneself.

Journals and dreams: even the formal materials of About Ed derive from private language rendered common. This effect is most pronounced in the case of Ed’s dreams. We learn quickly that Ed is a talented dreamer, who tells Bob “every detail of his dream, the dream before that and the dream before that, retreating into the night. Not shreds, cinemascope.” The dreams compare positively to artmaking. “My poems and Ed’s paintings are dated, but Ed’s dreams speak the era [of the ’70s]—paranoia and spasms.” Ed’s dreams puncture the book until they become it, in an unbroken fifty-page sequence in the first person. The orthodox Freudian position treats dreams as a symptom meaningful in private only, their significance no more transferable to another than the experience of mourning. Glück breaks both prohibitions—he has to, in this psychic commons.

In his chapter on Ed’s tomb, Glück quotes the seventeenth-century Japanese poet Bashō’s death poem: “On a journey, ill, / and over withered fields dreams / go wandering still.” Dreams wandering after death: the formal promise that About Ed’s final section fulfills. Poets across regional and linguistic traditions use different techniques to turn language into public memory of death; Bashō’s death poem in which dreams replace sickened life couldn’t be more different from, say, the Roman poet Horace’s boast to have made a monument “more lasting than bronze.” Inverting the most ephemeral language possible into a memorial, Bob-cum-Ed replaces life with dream syntax. Glück takes inspiration from Ed’s tomb to “write [his] stories posthumously, image replacing image.”

In his interview with Ives, Glück nods at a Gnostic aphorism from the Gospel of Thomas: “When an image replaces an image, then you will be in heaven.” So Ed’s tomb is heaven? If so, it’s a secular afterlife, continuous with and on display to the world of living people, and spilling over with them, too.

Kay Gabriel is the author of A Queen in Bucks County (Nightboat, 2022) and the Editorial Director at The Poetry Project.