THE FIRST THING I NOTICED about 1962’s Cléo from 5 to 7, one of the more enduring hits from filmmaker and artist Agnès Varda, is that the run time is not two hours but ninety minutes. Where did those thirty minutes go? How did she make a “real-time” film that doesn’t execute its promise? I always neglect to keep tabs on that missing half hour; I’m enjoying the film too much. Such is Varda’s slippery genius. She creates a structure, then leaves just enough room to show you how she did it—if you know how to see it. Varda knew all about the difference between looking good (as her characters often do) and being good at looking, as evidenced by her technical rigor and conceptual daring. The risk, always, is that the viewer might conflate the two. I did.

I came to the Nouvelle Vague all wrong. I picked my way through the mall, coming out with a bouquet of Criterion DVDs stolen from Borders. Mostly Jean-Luc Godard: French names, and black-and-white imagery being graspable signifiers of a vague, artistic elsewhere, anywhere but a weird little Quaker town in Southern California. For me and my best friend, watching Godard’s early films was like homework. We tried to launch ourselves off the floral couch of aesthetic turpitude through self-abdicating rites of grooming and consumption, mimicking Godard muses like Jean Seberg and Anna Karina. We smoked in cafés that served coffee in Styrofoam cups and kept a shelf of puzzles with pieces missing. We did not look good. At the height of my inchoate adolescent pretentiousness, I was unaware that Agnès Varda even existed. If I had known her work back then, I’m sure I would have emulated Cléo’s hair and wardrobe rather than allow myself the grown-up pleasure of being unmoored by Varda’s kaleidoscope of shifting imagery and meaning. Now, I am drawn not just to Varda’s visual style but to her deeply felt and deceptively playful point of view, which, over her sixty-year career, became increasingly complex.

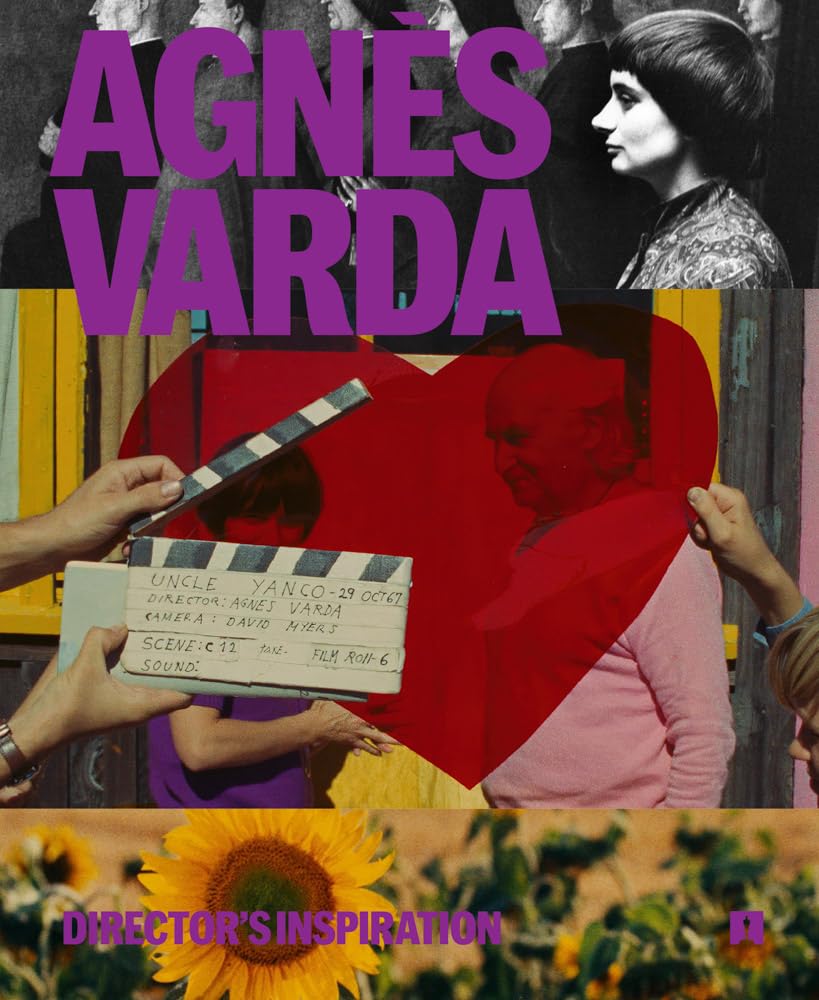

A tension between lightness and rigor informs Agnès Varda: Director’s Inspiration (Academy Museum of Motion Pictures/DelMonico Books, $40), the catalogue accompaniment to an exhibition nestled within the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures’s ongoing “Stories of Cinema” series. The book spans the entirety of her career, bookending her years in cinema with her first career as a professional photographer and her septuagenarian renaissance as an installation artist; each act is clearly informed by the one that came before. Although anchored by an interview and a couple of serious essays—the kind of long-form, thematic writing endemic to art catalogues—the book can’t seem to land squarely on either intellectualism or playfulness. Sasha Archibald’s essay on Varda’s relationship to Los Angeles is very good. Elsewhere the book conjures a word I hesitate to put down but has been haunting my deep dives on Varda: girlishness. The brightly colored pages, scrapbook-style layout, and graphic pull quotes bring to mind It-girl tomes like Chloë Sevigny’s self-titled 2015 Rizzoli book. Women’s cultural products tend to masquerade style as unearned seriousness—it is their chief offense. Director’s Inspiration takes the opposite risk, presenting a body of work from a groundbreaking artist through the aesthetic of a mood board. It mostly works, capturing the spirit of Varda’s difficult, feminist, and paradoxically coy ethos. That “difficulty” as an artist always served the buoyancy of her work. Given the number of honors she received (very) late in life, it’s worth remembering that the buoyancy was not fully apprehended or appreciated as the work was being made. Ironically, Director’s Inspiration provides a better picture of that balance through its limited purview than much of the later analytic writings on Varda (including the competing theories on where Cléo’s thirty minutes went). It’s a book only Hollywood could make, and that is not without its advantages. The juiciest parts by far are the short testimonials from those who collaborated with her or otherwise lived in her creative orbit—Martin Scorsese, Chloé Zhao, Sandrine Bonnaire, Jane Birkin, and Varda’s own children, Rosalie Varda and Mathieu Demy. Friends, family, assistants, French icons, and industry Brahmins are all given the same space. There is a pleasing contradiction between the many photos of Varda looking frankly adorable in a bowl cut and funky jewelry, and the firsthand testimony of her technical working methods and blunt self-regard. Scorsese writes that he “was never quite sure” if Varda liked his movies, admitting, “I guess I wanted her approval.”

Every director does. I wanted it before I even knew how. In my high school diary, among the flushed and fragmented entries that don’t reveal a self so much as catalog poses of selfhood, one sentence rings oddly true:

“I want to be an eighty-year-old girl.”

What the hell did I mean by that? I couldn’t know it then, but I was looking for someone like Varda, who died in 2019 at the age of eighty plus ten. I hadn’t found the artist who knife-edged her films with precision-cool cinematography, and who couldn’t care less if boys liked her (but knew how to lasso their respect to her work). When director Kimberly Peirce, film editor Kate Amend, and actors Jessica Chastain and Angelina Jolie presented Varda with a Lifetime Achievement Oscar in 2017, she noted in her acceptance speech that no men were introducing her: “I want to thank the four bright and beautiful and intelligent women who spoke,” Varda began. She put her hand on her chin. “And I have a little question: Are there no men in this room who love me, to speak up?” The audience roared. Some of the men in the room, including Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks, stood up and waved their arms. This was her feminism: wry, observational, playful in presentation, and dead fucking serious in its implications. She went on to point out, to a room full of peers from the organization that would eventually publish this book: “I’ve been under-loved and underpraised, I would say, because I try to work to get the essence of cinema. . . . I am not bankable.” If coquettishness was her entry into this sleight, it’s because Agnès Varda, the artist, the cineaste, the auteur “who could have done everyone’s job on the set,” as her former assistant, director Lynne Littman points out, knew the gambit was in service of nothing but the freedom to say what she wanted. That same year, I met Varda at an Academy screening of Faces Places, her 2017 documentary made in collaboration with the French street artist JR. I wanted her to like me immediately. She was tired. Always pleased and slightly puzzled by her newfound It-girl status. “I think you should not introduce a film because a film is a film,” she said. “But I get it, you want to see the beast. Like at a circus.”

Nearly two decades earlier, I saw a photograph of her on a pre-Tumblr message board: an elderly woman with a maroon-edged bowl cut, seated behind a camera, headphones on, looking exceptionally calm and pleased. Her body leans into the camera, save for her right hand, which holds the hand of the man sitting next to her. I had no idea who either of them was, but that image held for me every promise of what it could mean to be a woman (a grown one, at that), to be an artist, and to be in love. That photograph continues to make the rounds of cyberspace and is, of course, featured in Director’s Inspiration. It’s Varda and her husband, the director Jacques Demy, during the production of Varda’s documentary-drama about him, Jacquot de Nantes (1991). Demy was dying of aids. Varda was getting him up every morning so he could draft pages of his memories of childhood in occupied France. Her re-creations of them are cut with brief interludes of the declining Demy, with the documentary sections acting as pauses between freewheeling depictions of play. Varda’s longtime assistant director Didier Rouget characterized the film as an attempt to prolong Demy’s life and ease his suffering. “Shooting took over six months,” he recalls, “and extended Jacques’s life by that amount.” How childlike is it to think making a movie can save a life? And yet, for a while, it did.

The images of her at work are the most inspiring aspect of Director’s Inspiration. There is a 1949 self-portrait in which she is lit like a film noir heroine but scowling like a schoolgirl on picture day. At the height of her powers, she looks eccentric, chic, in control: leaning over the camera with a cigarette dangling out of her mouth on the set of Uncle Yanco (1967), looking louche with sunglasses on her head or smoking in a bathrobe on the set of Lions Love ( . . . and Lies) (1969). If I’d seen these images in high school, I probably would have tried her bowl cut, I probably would have looked like an asshole. But it would have been a way in. Images of Varda usually lead somewhere deeper. The aging of her own body is woven into later films like The Gleaners and I (2000), and she still regards the crevasses of her hands with the curiosity of a child. The calibration of feminine energy to an almost coquettish degree, an ironic air of girlishness, persistent at eighty and beyond, became the sugar of her sharpness. “Voices like Varda’s are essential,” Zhao writes, “because, just like the world we live in, masculine and feminine energy in cinematic storytelling is out of balance.” Varda knew you have to be a kind of monster to finish nearly forty films in a lifetime. But you don’t have to act like one.

Christina Catherine Martinez is a writer, artist, and comedian in Los Angeles.