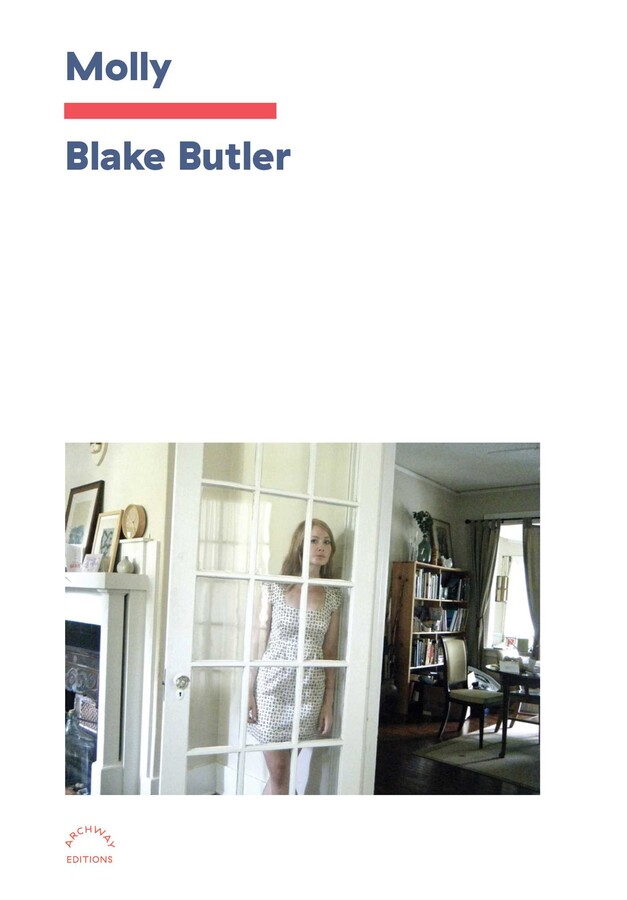

IN THE POEM “POST,” from her posthumously published collection, The Cipher, Molly Brodak writes:

The dead come back

not for you,

for themselves,

to hear their own stories

for the first time.

I couldn’t shake the feeling while reading Molly—writer Blake Butler’s anguished chronicle of the decade he and Brodak, his late wife, spent together—that she was listening in, and that she and I had surfaced from some underwater place to bear witness to Butler’s act of witnessing, to choke down his story of her life and death, and of their entanglement, with all its mercilessly serrated edges. Molly, unsurprisingly, is a resurrection animated by loss and its affects, from shock to grief, anger to guilt. As a text, it is promiscuously digressive, polyvocal, and sort of messy, calling on those who encounter it to ask: How should a grief memoir be? This is a formal and familiar query—can language suffice as a container for trauma—but it is also, urgently, a relational one: How should readers and critics receive the suffering of others, and what does a post-traumatic account demand of its audience? In literature, as in life, fear often permeates these points of contact. “I’m sick,” the speaker of “Post” admits after surveying her world, “looking has made me / sick.” We seek distance and summon disavowals, disquieted by the threat of infection.

In Butler’s telling, his relationship with Brodak was thorny from the jump: “The first time I met Molly,” he writes, “I picked her up from jail.” There had been a mishap with a borrowed car; Brodak was stopped on her way to their date with expired tags. Their night teeters between the commonplace and the strange: after he bails her out, the two pass intimacies back and forth at a bar. Brodak shows him an MRI scan, worried over the possible return of a brain tumor. The next morning, she tells him she loves him. As in much modern romance, though, things are intermittent until they aren’t. Despite early hesitations and infidelities, his drinking and her casual cruelty, they stay together; they buy a house in Atlanta where they raise chickens; they wed in 2017.

There’s something of the Sylvia Plath–Ted Hughes marriage (or rather, its tortuous mythography) hung like a shroud over Molly. Two young writers—both difficult, the marriage difficult—cleaved by affairs and, later, suicide. In life, Brodak was best known for her 2016 book Bandit: A Daughter’s Memoir, her reckoning with the looming godhead of an absent father. Like Hughes’s version of Plath, Butler’s Brodak is a little ruthless, preoccupied by damage, and sort of dour. Brodak’s late poems, like Plath’s, are riven by apocalyptic tableaux and selves in the process of being sheared or disintegrated. Like Plath, Brodak often baked when suffering writer’s block. Baking, she would tell a local paper, “is a loss of self,” a useful practice of “not thinking.” According to her diaries, as Butler divulges, she was reading Plath’s Ariel in her last week (the poems were “extremely accurate,” she noted).

I suspect the resemblance is by Butler’s design. On her last day, he writes, he finds Brodak “in the kitchen with the lights off, standing as if dazed by my appearance, arms at her sides.” The room in his memory is “dim, traced with a glow. . . . she seemed to hover there.” This portrait of the poet in stupefied distress eerily echoes Trevor Thomas’s description, in his brief memoir Last Encounters, of Plath in the hours before her death. Thomas lived in the flat below hers, in Yeats’s house, and that night he’d found her in the hallway outside his door, standing with “her head raised with a kind of seraphic expression on her face.” Butler asks Brodak about her manuscript, mentions Whole Foods, and heads out for a run; Thomas says he’d “have to go or I wouldn’t be able to get up in time.” Both men sense something is horribly out of joint. But frozen there, Plath tells Thomas not to worry: “‘I’m just having a marvelous dream, a most wonderful vision.’” Brodak says to Butler that his suggestion of a “movie” and a “nice night . . . sounded good.” She does not move.

The ruptures that follow these scenes—Plath’s suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning, Brodak’s by gunshot wound—are narratable, yes, but skirt flat recognition. They elide knowability.

This is the unbearable knot at the center of life writing: the epistemological discontinuity between what happened (an unintelligible specter) and the infinitely varied and subjective stories we produce about those experiential phantasms. As a memoirist, I often wonder: What do we owe the people who fill out, obstruct, and enrich our lives? What responsibilities do we carry as stewards of the narratives we weave? As critics, this dilemma further constrains our evaluative gestures, especially in appraisals of the (auto)biographical work of contemporary others. How should the critic—that is, how should I—adjudicate the snarled stuff of a stranger’s life? Am I a prosecutor or sleuth? An analyst or empath? A mediator or soothsayer? My sense is that the critic of true rigor must dazzle in all. In my encounter with Molly, I’ve tried to meet it first as a text, which is to say, as a knot of language I am, at least in part, tasked with undoing. But I also respect its work as the testament of a fellow sufferer, someone whose dignity and grief should and must command my attention—another wanderer.

In recent years, most talk around life writing (and, indeed, the much-contested genre of “autofiction”) has been hung up on its ethical dimensions. In the wake of #MeToo, it’s become de rigueur to subject personal writing to heightened suspicion: Who are you accusing, and of what? To what end? Do you really “have the right” to confess this? In accounts of trauma, the teller is now also often understood to be a kind of dupe or patsy, the ventriloquist’s dummy of a marketing apparatus economically orchestrated around bad affect. The question becomes, then, one of the confessional subject’s cultural savvy and intelligence (or lack thereof), and the extent to which their story is co-opt-able by a capitalist machine that exceeds them. The extra-narrative bedlam enveloping figures like Plath and Brodak suggests, however, that this ethical obligation covers us, also: we, the confessors.

IN A LETTER TO JACQUELINE ROSE [1]—who was completing a study of Plath at the time—Ted Hughes wrote that critics sustain an “atrophy of the moral imagination” in the course of our work. By positioning ourselves as the intellectual arbiters of a text’s cultural import, he argued, we subordinate the work of others in service of our own, and, in so doing, exploit a narratological power to “ransack . . . and reinvent” those others, both living and dead.[2] Like Janet Malcolm’s treacherous journalist, Hughes’s critic is no better than a vulture, scavenging the carrion of others’ lives to pin their findings behind glass, to present these specimens “in front of classes” as inert objects of academic interest, and then (of course) to designate the project as an “exemplary [and] civilized activity.” Such ventures, Hughes sneered, prove that for a “person to be corrupted in that way is to be genuinely corrupted.”[3]

There’s a disorienting scene in Malcolm’s 1994 book The Silent Woman—her own narrative intervention in the Plath–Hughes mythography—that reproduces this letter from Hughes to Rose and exhumes a meeting between Rose and Malcolm in which the two critics directly address the accusation. “It’s an interesting perspective,” Malcolm offers, before Rose adds,“it’s an argument against the right to do criticism,” an argument that, moreover, presupposes a singular and indisputable truth of experience, a truth that, in Hughes’s philosophy, may be possessed only by the people who’ve lived through it. It’s plain neither Rose nor Malcolm bought Hughes’s claim; after all, each went on to publish her Plath book in spite of it. Perhaps, though, it’s what spurred them to render their works so transparently meta-critical, even confessedly—and ambivalently—partisan.[4]

But despite his decades-long refusal to comment on the intimate matter of his dead wife’s life, Hughes, too, stank of what he understood as the biographical enterprise’s rot. As the years passed, he would reveal he’d destroyed (or “lost”) Plath’s last journals, re-fabricated the completed manuscript of her Ariel poems, and—with total control of her papers (the two were separated, but Plath died intestate)—installed an official biographical narrative that frequently demonized her and sainted him. Hughes, too, became a ransacker, a reinventor; the wife he’d left for his beautiful mistress became, in death, his specimen also.[5]

These are disciplinary measures, and their logic contaminates Hughes’s philosophy that there existed, beyond him, an empirical truth concerning the wreckage of their marriage. Inside his fantasy of objectivity was a sublimated desire, or else a dream: one where his wife’s history and her death were subject to fixed and unified truths; one where he had the good fortune of playing the intellectually dispassionate executor. In such a dream, the story would be his and his alone—one rendered uninterpretable, entirely beyond the moral stain of criticism.

If, in Hughes’s thinking, the psychic excess and intimate too-muchness of Plath’s life required guardrails and mandates of privacy, Butler’s project in Molly takes the opposite tack. The unknowable might be found through a kind of narrative flaying, an unadulterated therapy of exposure. He exhorts his reader, too, to peer into the very worst of it. “I see Molly’s story as a tragedy,” he told the Daily Mail. “I felt her story needed to be told and had a purpose in the world.”

Molly, in his view, performs storytelling as reparation: for those in suicide’s dark orbit, Brodak’s struggle—and, in the wake of her death, Butler’s own—might facilitate processes of curative identification, or at the very least, of recognition. As a “tragedy,” though, Butler’s version of Brodak is also a cautionary tale served raw, the story of how secrets kept can dissolve whole lives. His gambit inverts Hughes’s, but their positioning within the biographical engine is not so different—each becomes the de facto arbiter of his late wife’s story. Where Hughes is tight-lipped and discursively constrictive, Butler claims to lay everything on the table—the warts-and-all recollection of their shared time. Still, concealment and transparency are inseverable companions; every story, after all, relies on what is withheld.

Early on, Butler boils Brodak’s history down to fourteen bullet points, comprised, in part, by the usual events: birth, education, marriage, death. The chronology of her life contains, as most lives do, an easily renderable outline. Butler’s shortlist is, here, the first of many attempts to make the lost beloved biographically legible, to “solve” the mystery of the other. But the singularities and detritus of a life, as Butler well knows, necessarily exceed the explanatory constrictions of lists, chronologies, and other biographical tools. He offers a dense, asphyxiating disassembly of their life together, her death, and the secrets that surfaced in its wake—about as far from hagiography as memoir tends to reach. Butler opens the book with one end to their shared story: Brodak’s suicide in March 2020.[6] It’s a typical maneuver in accounts of artist-suicides, this beginning at the end, but also a precarious one. In the effort to master or circumvent suicide’s unsolvable riddle (“why?”), the subject’s life—which now shadows the mise-en-scène of their death—becomes merely expository. Suicide is made teleological. It is inevitable, the thing toward which everything before it aches.

Butler’s diagram of Brodak’s last day is an emotionally taxing read, laid before us with an investigator’s (or a novelist’s) eye for the way disparate gestures and minutiae amass in the shape of a plot. Leaving for a jog, he takes his

phone out to put on music I could run to and saw I’d received an email, sent from Molly, according to the timestamp, just after I had left her in the room. (no subject), and in the body, just: I love you, nothing else, besides a Word document she’d attached, titled Folk Physics, which I knew to be the title of the manuscript of poems she’d been working on the last few months. I stopped short in my tracks, surprised to see she’d sent it to me like that, then and there. Something felt off about it, too out of nowhere—not at all like Molly, or perhaps too much like Molly. I turned around at once and went inside. . . . Molly seemed to clench up as I came near her, letting me put my arm around her once again, but staying loose, confused, on edge. I realize now she must have had the gun on her already. . . .

Near the end of the run. . . . I pulled my phone out to see how far I’d gone and saw a ping from Twitter telling me that Molly had made a post, just minutes past.

On returning, Butler finds a note taped to their door, indicating her plan; after this, the order of things falls apart. He runs back out, thinking there might yet be time to stop her, but it’s too late. Immediately after he discovers her body, the state transforms Butler’s loss into the punitively arbitrated story of a crime scene, a story—whether witness to or suspect in—he “wasn’t allowed to leave” and one he’s impelled, instead, to narrate over and over again in conversation with various officials, hardening her death in the amber of testimonial language. Her suicide note, now, is no private missive but a legal document: it is evidence. Brodak, Butler considers, would have taken a “sick satisfaction” in the procedural elements of the fallout, the event’s “programmatic existential framework.” Before this, Butler’s shock disorients the narrative. As he calls out to her in his search, her name feels, in repetition, less and “less like her; as if what those syllables had meant to me for so long no longer bore resemblance to” her name. A witness he encounters groans in “some broken bit of useless language.” The borders between speech and knowledge grow permeable and dissolve.

Butler has faith, for a time, that if he defers speaking Brodak’s suicide aloud, it might yet be undone, like time could be halted or, with diligence, reversed. His knowledge is not his alone, though, and as the “widening hole” of her death is tidied by factual records and police documents, a leaden reality settles over it. People “would know soon,” and the information would “become old news, gossip, word of mouth.” Such is the order by which a person’s irreducible existence becomes cold hard data. Brodak, here, is shuffled into the ranks of Malcolm’s “rightless dead.” As Butler transcribes this sequence of events, he is haunted by the question of ownership, a feeling that it’s “strange to tell this story as if it’s mine.” Molly, indeed, often feels like Butler’s apprehensive attempt to wrest control back from the circling vultures, the gossipy chatterers whom Plath, in her “Lady Lazarus,” famously calls the “peanut-crunching crowd,” so ravenous to unwrap and masticate her confessing Godiva.

In Molly, Butler wants to know and doesn’t. This splitting sensation saturates the book’s most textured and troubling sequences; the strangeness of that feeling elaborates, in real time, the incompleteness and excess of psychic life, the desire that lives disorientingly inside all writing. As the story of a marriage, Molly sees that desire, like love, can be both ignited and fractured by the unknowability of the other. So much of the difficulty between them, Butler admits, originated in moments of miscomprehension, when “each [stood] at different ends of a conversation.” Words illuminate and obscure meaning in alternating measures. This wire-crossing, though, can also create the space in which empathy is born. We extend generosity not despite but because of the limits of our understanding. “For Freud,” Rose reminds us, “the utterance can only ever be partial, scarred as it is by the division between conscious and unconscious.” Molly compels most powerfully when it grants space to this indeterminacy.

At other times, Butler tries his hand at decoding and translating the more enigmatic aspects of Brodak’s history. On her mental illness, for example, he lists toward a pathological reading, asking himself, “How can that last fact—took her own life—not automatically restructure all the rest?” Confronted by the lacuna of loss, his narration shores itself against uncertainty with offhand facts and allusions to fate, vague spiritualisms, specters, even demons. She “was troubled,” he tells us, “that was clear,” and “death always seemed to be on Molly’s mind.” At one point, Butler presents the symptomatic criteria for borderline personality disorder and remarks that it’s hard to “read the DSM-5’s description . . . and not find Molly there in every line.”

In her autobiographical writing, Brodak didn’t shy away from diagnostic language. Of her shoplifting, she writes in Bandit that, “It’s a little sociopathic. This conscious break with reality I am describing in the method of stealing. I know it is sociopathic.” She later ties her self-assessment to a question of psychic inheritance, voicing her suspicion that such sociopathy may have been passed down to her by her father. Brodak’s philosophy of morality is fascinatingly changeable: a person’s behavior only becomes a categorical identity through the process of naming. When her father is first arrested, this situates him within an axis of criminality. To crib Simone de Beauvoir, her father is not born a “robber” but rather becomes one, and this legal interpellation “solved him” for Brodak in a way nothing else had. As readers and critics, we don’t have access to the recollected knowledge of a given memoir; still, it’s urgent we remember that the form, even in its longing for “truth telling,” is comprised of deliberate representative strategies. Both Butler and Brodak find emotional truths in psychological dictates. How this language and these frames shape the portrait we are given remain open questions, textual activity.

Even a diary—and certainly, a writer’s diary, with its expectation or hope of posthumous publication—is written toward an audience. In the case of Brodak’s journal, Butler ventures that she intentionally withheld damaging information from it and left it out for him to discover. “Oddly,” he writes, “her personal writing never mentioned her affairs in any way, the same way that her suicide note had steered around them, too, along with so many other traces of the truth.” His unacknowledged faith that there exists some single, biohistorical truth—always, of course, just over there—sustains Butler’s memoiristic energy but his failure to hook it or to make peace with its more frighteningly possible nonexistence generates the book’s more subterranean, textural points of psychic friction. Who was Molly, really? Why had she done this? How do we make meaning from meaninglessness? These are only further snags in the tapestry.

OUR NARRATIVE DECISIONS, YES, accumulate and congeal; they have a kind of strange density to them. Earlier, I drew a parallel between the Plath–Hughes marriage-mythos and Butler’s union with Brodak. Unspoken or not, I revealed, in this move, my predisposition toward the women in each. I confess—that word again—there are moments in Molly when I bristle against Butler’s pathologizing diagnoses, particularly as I read them within a historical context of medical and psychoanalytic misogyny. I am constitutionally troubled by instances in which women’s account(s) of themselves are undercut, repurposed, or otherwise repositioned as unreliable. There is a scene, for example, in the middle of Molly, where Butler implies that a story Molly told about being held up at gunpoint during (what seems to have been) an attempted rape may have been invented to manipulate him. Though he writes that “presenting this information in the context of it having any question of validity makes me feel ill,” that particular damage is done. We, too, now question the authority and legitimacy of her testimony. And it made me feel ill.

Butler appears to anticipate our likely dis-ease alongside his own. One method by which he negotiates the conventional memoir’s narrative authoritarianism is by mingling Brodak’s writings—her poetry, excerpts from Bandit, diary entries, emails, and even the full text of her suicide note—with his own. Whether this interlacing truly enables her to “speak for herself” is debatable. Molly is nominally dialogic, but the dead, we know, cannot talk back. Butler has, in his fashion, the final word.

There’s a shocking series of revelations in the book’s last pages that unravel nearly everything you thought you knew about this memoir of grief. (If you are sensitive to spoilers, you might want to pause here.) As he attempts to conclude their story, Butler writes that Brodak—in addition to his discovery of her habitual unfaithfulness—was “grooming” and dating her students and had “controlled me and abused me” throughout their relationship, acknowledging that this naming of abuse was something he “would have never imagined saying about her when she was alive.” With this confession, Molly becomes a different sort of narrative beast, far stranger and more morally complicated than it already was, a memoir not just of loss and nonexistence but of accountability, as refracted through a wholly different sort of trauma.

To grieve those we love is challenging enough; to grieve—and to forgive—those we love who’ve caused us significant harm is something else altogether. I wonder what sort of story Molly might have been had Butler clued his reader in to this intimate ambivalence earlier on, whether I would have been a less paranoid reader, if, perhaps, my predilection for recognizing their marriage through the mythos of another literary history would have been more simply bracketed. Certainly, I found myself combing through earlier sections of the book again, trying to find what I had missed. Like any reader, looking from the outside in, I know the gaps in my “knowledge” are legion.

With Butler’s last reckonings, Molly’s ethical questions shift. Even as Butler assembles his allegations, he acknowledges that his proximity to this trauma—which is bound up, for him as for many survivors of abuse, in a complex, often contradictory flurry of loving affects—distorts his narrative capacity. As such, he registers his inclination to “relativize [his] own experience” in comparison with the histories of other survivors; he gives grace to Brodak’s own victimization inside a cycle of familial harm, “the extent” of which he now will never fully grasp.

The question of whether a person has the right to tell the narrative of a life—a narrative that will always only be a partial telling—is, I think, a wrongheaded question, one that usually leads to bad faith interpretations. Molly isn’t, and could never be, the “truth” of Molly Brodak. It’s Butler’s truth: one among many. As Brodak writes in Bandit, when the material fact of experience escapes us, the remainder is what “is always left: the story. And the story is the most dangerous thing there is.” Brodak’s story leaks beyond the bounds of Molly. Even with such vast documentation, the transposition of a life into writing is ineluctably, profoundly fragmented. Our selves are irreducible; this is where our beauty lies.

Jamie Hood is a poet, memoirist, and critic based in Brooklyn. She’s working on her second book.

[1]. The Haunting of Sylvia Plath, 1991.

[2]. In Janet Malcolm’s phrasing, this process of concealment is foundational to the tidying “apparatus of scholarship.”

[3]. Italics mine.

[4]. Rose took great pains to establish a critical and psychic division between the “fantasy” life of writing—what she understands in a psychoanalytic capacity as the “difference of writing from itself”—and lived experience, a division she further elaborated on in a 2002 essay for the London Review of Books concerning her disputes with the Plath estate. Malcolm, meanwhile, admits to her investment in salvaging Hughes’s reputation from the muck of biographical “busybodyism.” She openly plays the role of, in critic Caryn James’s estimation, the journalist-as-antihero. Her fascination with the poet becomes infatuation.

[5]. The two books Hughes wrote about Plath’s life at the end of his own—Birthday Letters and Howls and Whispers, both in the confessional mode he’d long disavowed—are, I must tell you, not only ideologically suspect but just plain bad.

[6]. I remember the news of her passing sending shockwaves through Twitter, though, like so much that happened that month, the particulars have become swallowed up in the fathomless horizon of loss ushered in by the COVID-19 pandemic. Butler recalls that her funeral was held the afternoon before his city went into lockdown.