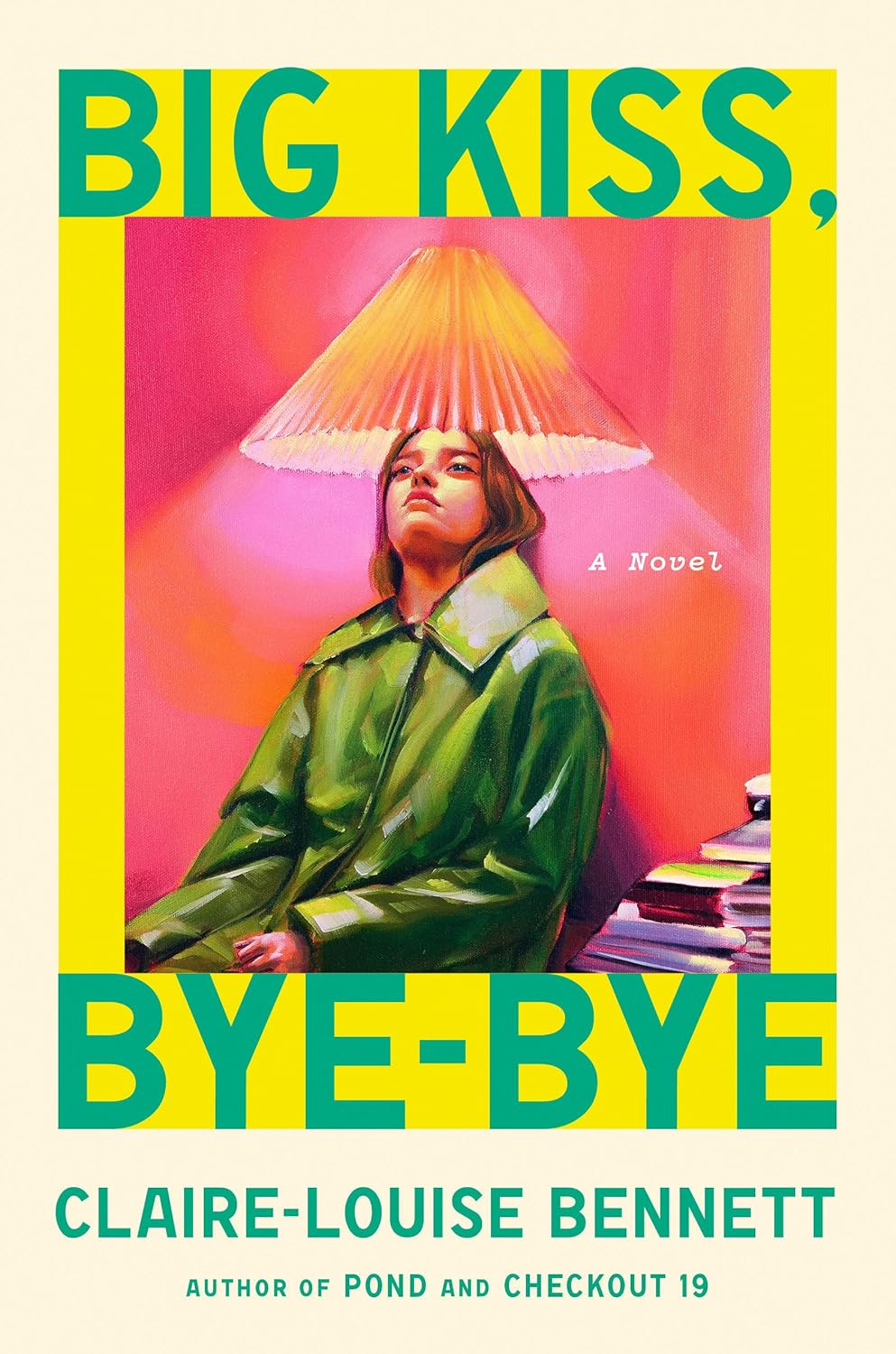

BIG KISS, BYE-BYE, Claire-Louise Bennett’s third book, begins in the long drawn out wake of a breakup. “Two weeks from now I won’t be living here anymore,” goes the opening line, told from the perspective of the unnamed protagonist. “I’ll be in the woodshed in L——.” The narrator, a writer in her late forties, is plotting her next steps, yet her thoughts keep drifting back to her ex-boyfriend:

Xavier won’t know I don’t live here anymore. We are no longer in touch. It’s been three months since his last email, which I did not reply to. There really was no way of responding to it. I sort of feel like calling him now—I wonder what he would say? But it seems irreversible, that’s really how it feels.

These temporal switchbacks—the start and stutter of narrative consciousness—are typical of Bennett’s prose, which eschews linear progression. Instead, her sentences swell then retreat, trailing away before sometimes doubling back again. After all: How do we know if an ending is truly irreversible? The narrator’s language betrays her uncertainty about the incontrovertible: “But it seems irreversible, that’s really how it feels.”

Bennett’s plots, like her sentences, double back, cut themselves off, short-circuit: they always seem in the process of beginning—or beginning again—whether you’re encountering them on the first page or somewhere in the middle. I admit, upon my initial read of Big Kiss, Bye-Bye, that I had some difficulty tracking its storyline, the basic “what happened?” of narrative. This confusion is intentional, and part of the reader’s experience of sympathetic identification emerges from the sense that Bennett’s narrator is no less confused than we are. The protagonist’s initial insistence on the impossibility of contacting Xavier soon lapses into a reverie about the last time they’d met in person, which then drifts into thoughts of when Xavier used to come around to the very apartment she’s now leaving, which collapse into memories of other men who had also visited her there.

Such palimpsests of disorientation seem understandable for a writer who has perpetually felt herself out of place. Born to a working-class family in Wiltshire, Bennett is technically a British novelist, though she has lived in Galway for over twenty years—a move prompted by the limited opportunities available to her in England. (In Ireland, her socioeconomic status did not feel as much an impediment to her writerly aspirations.) Only upon the success of her 2015 debut, Pond, did Bennett find herself traveling more frequently back to England, embraced by the literary elites to whom she previously had no access. This uneasy, roundabout homecoming colors Bennett’s books, often described in terms of autofiction. Written in the first person, Pond follows an unnamed woman who, like the author, abandons her dissertation and moves to a cottage on the west coast of Ireland. Her second novel, Checkout 19, returns to Britain and presents a kunstlerroman of working-class girlhood, offering a portrait of a young woman who works, per its title, at the grocery checkout. At her deadening day job, the narrator escapes into other people’s stories: novels, memoirs, and philosophical treatises that show her how a person might think and be. If Pond is about absconding back to nature, and Checkout 19 is enmeshed in the frenzied circuits of capital, then Big Kiss, Bye-Bye is a blend of the prior two works, taking place somewhere between city and country. Throughout, the narrator oscillates not just between future and past, but between her temporary new home at the woodshed, which she describes as “nowhere permanent,” and the city she leaves behind.

The night before the narrator moves out of her flat, she has a dream, which she meticulously replays over the following days. The dream is itself about moving. As she tells a friend the next day: “In this particular dream I was leaving one room that had crumbling plasterwood, to go to my room which smelt of marjoram and had a gritty bare floor. On my way out of the other room, which was commodious and largely empty, apart from some very old-looking travel chests far away, I notice a small scorpion on the ground floor.” This small scorpion looms large, but the narrator details how the architecture of the surrounding rooms enables her to circumvent it: “The space between my room and the room I was leaving was also sizable, and square and the two doors, the door to my room and the door I’d just come through, were not side by side but diagonally opposite.” The space—and slant—between the two rooms presents an unexpected gap for escape. And the dream ends with the narrator approaching the scorpion from above: she, a writer, drops a big book on top of it.

Big Kiss is a sort of transitional piece, and, appropriately, its narrative is almost entirely constituted by transitions. There is, of course, the protagonist’s romantic fallout with Xavier, which sets her storytelling in motion. (As the reader soon learns, the rules of no contact are hard to follow; the narrator will spend much of the remaining pages returning to Xavier, whether by memories or, eventually, phone calls.) At a more material level, there are the transitions between physical spaces—not just moving from the city flat to the rural woodshed, but also, once at the woodshed, between inside and outside, upstairs and downstairs, one room and then the next. Some of the best writing in the book takes place in literal transit, concerned with the logistics of moving and, well, moving. On her way to her new rustic lodgings, the narrator sits crammed in the backseat of a friend’s car: “I held a glass lamp in my lap and my feet were lightly resting on a box that contained a significant teapot among other things. A maidenhair fern trembled beside me, and there were cushions and a rucksack bulging with jumpers piled behind me.”

“Surrounded by many of my belongings,” the narrator recalls, her body recedes, just one object among the many she crates around. These passing scenes might appear tangential—as interstitial as the episodes they depict—but in Bennett’s novels, descriptions of characters traveling from one space to the next form the central drama. Here, it is not only setting that’s often constituted as and through movement, but also ceaseless dislocation that comes to inform what we know to be character. Bennett’s peripatetic protagonists are both physically and psychically unsettled.

At the woodshed, Bennett’s heroine is hardly alone in her thoughts: memories of Xavier, and ghosts from her more distant past, keep intruding. She receives a trickle of emails from Terence Stone, an old A-levels English teacher newly eager to be in touch upon learning that she’s a published writer. This protracted and largely banal correspondence forms much of the fodder upon which the narrator’s restless, overworked mind ruminates. She obsessively scrutinizes Stone’s missives, partly because she struggles to pinpoint exactly how she feels about the fact that he is writing to her: “One day I found it touching, the next I was utterly incensed by it.” It’s unclear what all this close reading will resolve, given Stone’s “relentlessly benign tone”—but in her rereadings, Bennett’s narrator suggests how we might approach the book at hand. What happened may or may not have much bearing on one’s immediate present. And even then, one’s immediate fixations might not be what truly concerns them at all: Stone’s letters consume the narrator in part because his unexpected reappearance triggers thoughts of another high school teacher with whom she “had dealings.” So much is situational, and Bennett’s narratives dramatize all the unexpected shocks and detours of what’s often ultimately uneventful. These are novels of disproportionate letdowns. You can hear it in the title: Big Kiss, Bye-Bye.

For all their internal monologuing, Bennett’s narrators remain tethered to reality through their ongoing attention to the physical world. Just as important as Stone’s epistolary style and syntax (much is made over the difference between one exclamation point versus two) is the material environment in which the narrator reads his letters. She finds spaces of transit—trains, planes, or automobiles—especially conducive to receiving and sending emails. Pond is an earthy book—attuned not just to the natural landscape in which it takes place, but also all the objects and commodities that fill it. (The reeds that thatch the cottage roof are not, as the narrator assumes, from “somewhere not too far away, along the River Shannon most likely,” but in fact from Turkey. “It’s cheaper,” the thatchers explain.) Bennett’s attention to the supply chains that constitute the cozy domestic havens of her fiction might be a testament to her own origins in a working-class family. As Clair Wills writes in the London Review of Books, “Bennett’s books are firmly ‘material.’” Her protagonists spend more time communing with places and plants, rather than people. And in that communing, they seem to arrive at a clearer understanding of themselves as social animals.

As the author once wrote regarding the “extraordinary scenario” of Marlen Haushofer in The Wall, in which a transparent wall separates its heroine from the outside world: “The only way a woman can experience solitude, without judgment and recrimination scuffing up against her peace, is if the rest of the world has come to a complete standstill and there is no one around to see her.” The wall in Big Kiss, Bye-Bye is not quite so literal, though the novel does take place during Covid lockdowns, where most people are retreating into isolation. The novel ultimately makes very little of this premise, given how its protagonist finds freedom, rather than restricted action, in social distancing. Following Haushofer, for whom loneliness enabled her “to see the great brilliance of life again,” Bennett views solitude as a kind of creative reprieve—“an emptying of the mind and a renewal of the senses,” as she describes it.

It makes sense that the constantly displaced and financially insecure writer would be attuned to the detritus of the material world. Bennett finds an affinity with other women writers with similar origin stories, such as Tove Ditlevsen, Ann Quin, and Annie Ernaux. These authors too are meticulously attuned to domestic minutiae, almost to an obsessive extent. As Bennett writes in her introduction to the 2021 reissue of Quin’s Passages:

It occurred to me some time ago that growing up in a working-class environment may well engender an aesthetic sensibility that quite naturally produces work that is idiosyncratic, polyvocal, and apparently experimental. The walls are paper-thin; you rarely have any privacy. . . . Your own skin is paper thin. When you are living from one measly pay cheque to the next with no clear sense of a future, day-to-day life is precarious, haphazard, fragmented, permeable, and beyond your control.

This description of Quin’s prose also applies to Bennett’s. Like her predecessor, Bennett draws on “polyvocal, and apparently experimental” (note the tonal eye roll) techniques not to obfuscate, but to elucidate the real conditions of living, and writing, from the perspective of the underclass. Far from the stylistic abstractions of modernist masculinist totality or the avant-garde elite, this is the prose, we could say, of precarity. Bennett’s heroines might seek shelter in rooms of their own, but the walls always feel treacherously porous. Beyond its deteriorating roof, the cottage in Pond is constantly being infiltrated by stray leaves that blow in through its windows. Such precise—even excessive—attention to mundane realist details is a sign of the working-class writer who cannot afford to take anything for granted. These are characters perpetually uncertain of interiority, whether their own or that of the rooms they inhabit.

On her first night at the woodshed, the narrator of Big Kiss, Bye-Bye reflects: “I wonder about those rare people who never move. Who live on and on in the same house. Never really needing to sort through anything. Never having to handle each and every object in turn. Never having to weigh up its value. Never having to ask, what do I take with me? Never seeing their life like this. All up in a heap.” Such a sense of stability she can hardly imagine. After all, Bennett’s characters never stay put in one place for too long. More often they are merely passing through, nomadic figures who never settle on any firm landing because they’re hardly certain from where they begin. But disorientation is not necessarily a bad thing, at least creatively. At the very least, unsettling—both psychic and physical—allows room for new connections to be forged, new doors to appear. Watch the gap: Bennett’s narrators do not live so much as thrive in rooms not quite of their own.

Jane Hu is is a writer living in Los Angeles and an assistant professor of English at USC.