A MAN LOOKS OVER A FENCE, SPYING. He notes the arrival of a Buick hardtop convertible. Parked now, the driver rolls the top down, using a new automatic mechanism, exposing the interior leather to the elements right at the wrong moment. The camera at first shows a magnificent three, who spill out as from a clown car: Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. Then it lands on Jimmy Schuyler in the back, who, doubling as a porter, carries the luggage.

So begins Presenting Jane (1952), a short film made by Harrison Starr and John Latouche. The boy poets and their beloved woman painter have taken to Long Island; it is summer, and this exurb is, or would become, their haunt. It’s afternoon and time to get down to the water. John presses his palm against the supporting column of the porch, while Frank holds his column more tentatively and tenderly. They stare out on the sound, gazing at Jane, now in the landscape she prefers to paint. A glitch occurs, and like a ghost conjured through splice, Jimmy appears behind them once again.

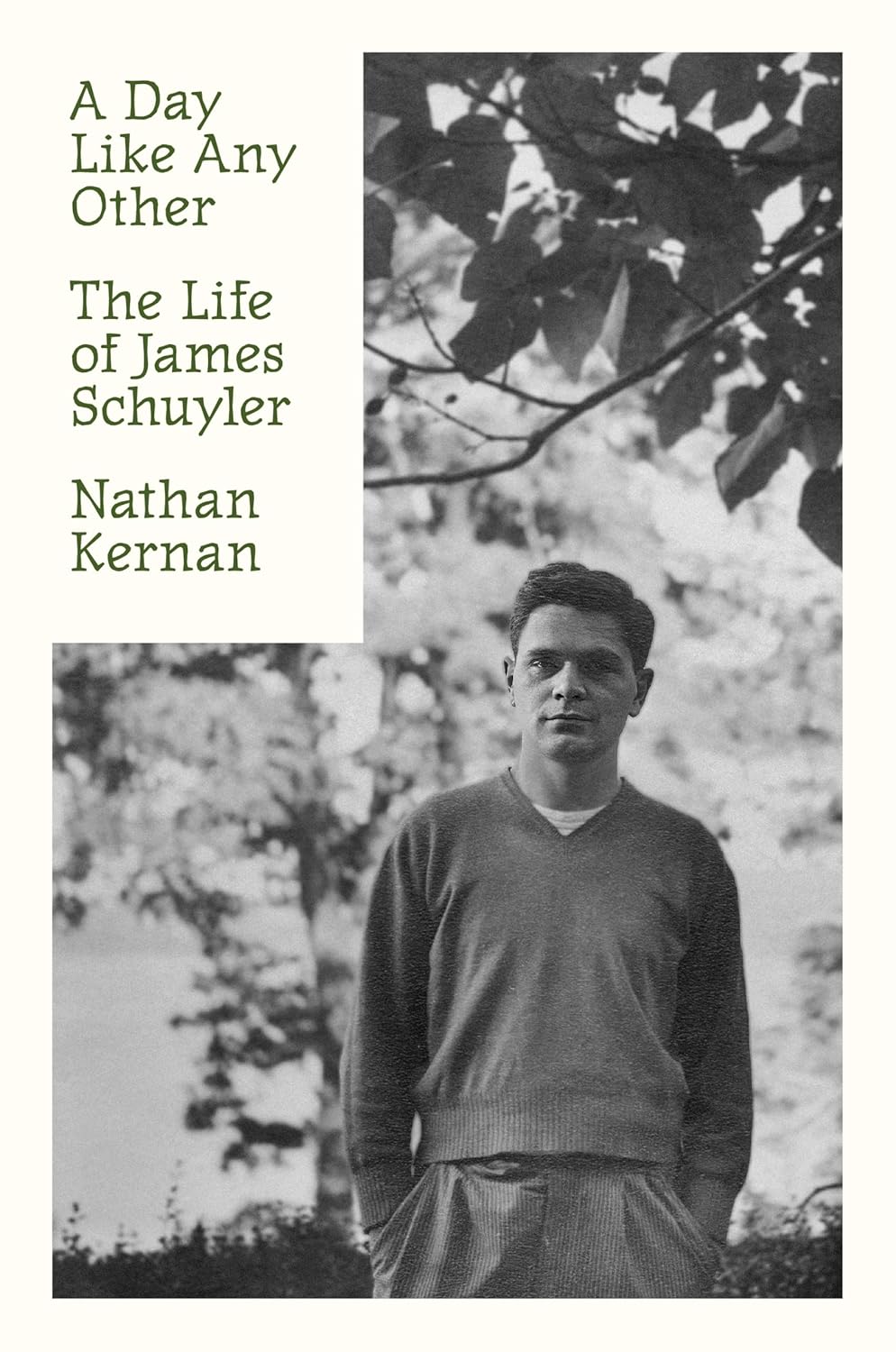

Whether a cutting error or the mark of the filmmakers’ artistry, this pair of frames—Jimmy standing twice behind his friends—reenacts, to some extent, how they are remembered. When most people consider the New York School, they’re most likely to remember the Harvard Boys: John, Frank, and Kenneth Koch, meeting as boys at the school’s literary magazine, The Harvard Advocate. A bit later poet Barbara Guest came into the picture. Finally, Jimmy arrived, a college dropout, having grown up in much greater precarity. But Jimmy didn’t remain behind for long. Of the five, he had the greatest early success, not just because of his poems’ achievements, but because that achievement was, in a word, recognized. He was the first to publish in The New Yorker. But he who shall be first will later be last: Schuyler took the longest to put out a book, and had the least celebrity and attendant security, of the group in his lifetime. A new biography of the poet, Nathan Kernan’s A Day Like Any Other,finally lets Schuyler stand out in front once more.

JAMES SCHUYLER WAS BORN on November 9, 1923, in Chicago, the son of a socialist midwestern newspaperman who could trace his lineage back to the Dutch settler fur trappers of what would one day become New York, and a socialist midwestern newspaperwoman whose people came from the farms of Minnesota. He then moved around a lot, finally finishing his childhood in upstate New York.

Schuyler too got his start writing for a newspaper—in high school. There, he discovered his great American poet queer ancestor, Walt Whitman, although it would be a long time before he identified with the poet part. Schuyler’s best friend in high school was also a gay boy, and they were out to each other, a first profound social experience. But otherwise, Jimmy was closeted, even quoted in the yearbook as wanting to have a lot of girlfriends. He had one then, but his first love was, incidentally, the other boy who from time to time went steady with Jimmy’s beard (much later, the boy was murdered in New York).

Before arriving in the city, Schuyler attempted college and flunked out; he then joined the Navy. He had his first breakdown in college after his father’s death; he subsequently went AWOL. After he turned himself in, he was imprisoned on Hart Island among the potter’s fields, and the ghosts of women prisoners. When he was released, he was dishonorably discharged for both his disappearance and for his sexuality. Back out in New York, broke, Schuyler’s friends began to figure out ways to provide for him—jobs, apartments, pin money. This would be a lifelong pattern: friends helped him live in ways that system and state tried mightily to prevent.

Incarceration on Hart Island left Schuyler traumatized; he had a tremor. He had acquired a fear of public speaking after the military interrogations he endured there, leaving him unwilling to read his poems before audiences for almost his whole life. (He had a second reason: poems were, for him, a written medium.) Not that there were poems yet. Schuyler’s first real genre was fiction, one he would practice until the end of his life—he was also a playwright and an art critic, never abandoning the newspaper form. Schuyler’s next seven years were spent in the company of a set of New York poets, but not the ones we associate with him or with New York. Schuyler first formed a deep friendship with W. H. Auden and his younger boyfriend Chester Kallman; rounding out the quartet was Schuyler’s boyfriend Bill Aalto. That Auden was a poet was incidental; the group loved the opera, they loved to gossip. In a way, Schuyler became a poet of New York before the Harvard boys even got going—except he still hadn’t made a poem.

Auden helped bring Schuyler to Europe for the first time. In Italy, Schuyler became himself again in two senses: first, he restored for himself his father’s last name after having taken his stepfather’s; second, Auden hired him as secretary and lent him and Aalto his house in Ischia, off the coast of Naples, where he began to write fiction more seriously. When Schuyler and Aalto’s relationship went from bad to worse (knives were pulled), Auden also helped get Aalto away from Schuyler and brought Schuyler home to New York. There, he “learned to make a poem before he wrote a poem,” typing up Auden’s latest manuscript, getting a feel for his lines by making them.

Kernan moves from describing this apprenticeship phase to retelling the meeting of the formal New York School, starting in 1951—the group partially captured in Presenting Jane the next year. John Ashbery met Jimmy first, and after Frank and Jimmy had published in the issue of the same journal, the three hung out. Frank recognized Jimmy’s greatness, and Jimmy started biting Frank’s poetry from that moment on. But that meeting led to a second pronounced manic breakdown, in which Schuyler, at the hospital, began to produce the first poems he’d be known for.

The next fifteen years of biography—from Schuyler’s first meeting with O’Hara until 1966, when O’Hara was killed by a dune buggy on Fire Island—require readerly patience of the kind demanded when sorting through who’s who in Tolstoy. They’re also the most unabashedly fun. For readers who already have a mental map of this socio-literary world, its pleasures are likely to be numerable.

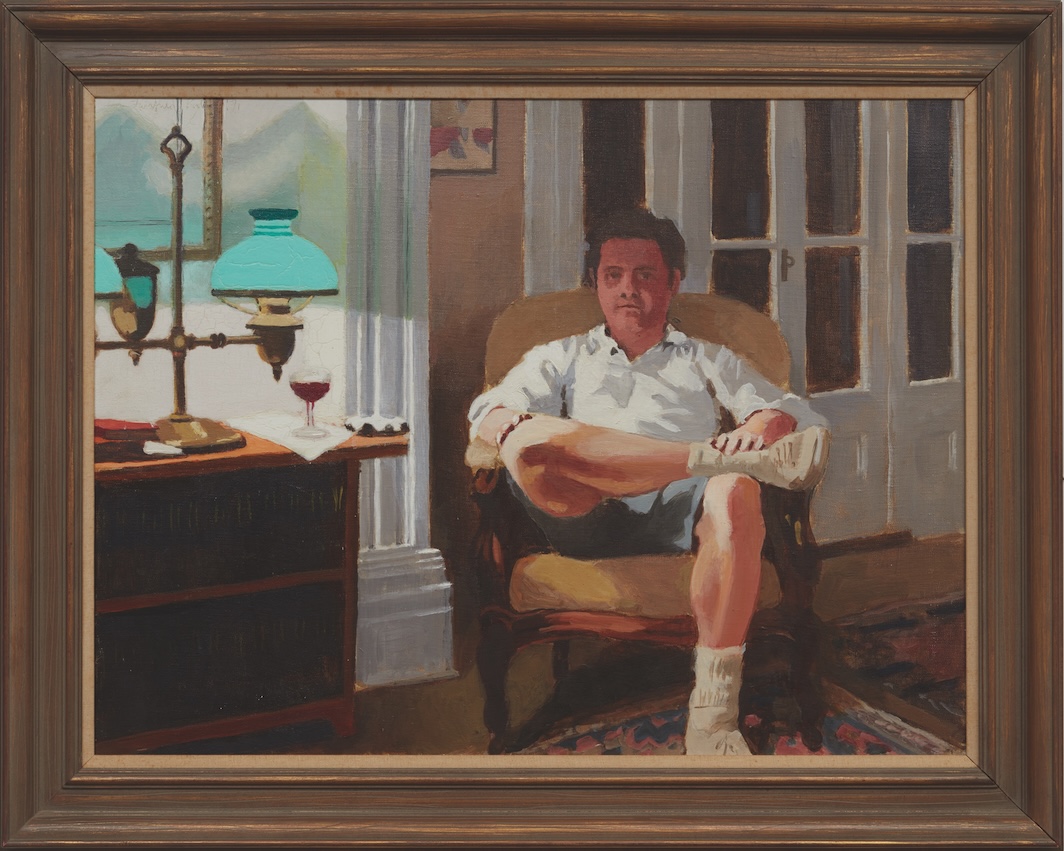

WHAT MARKS THE WORK OF THE NEW YORK SCHOOL POETS is their attention to daily life and everyday activities: going to country homes, passionately engaging with art and music, meeting up, going to dinner. This has been termed “I do this, I do that.” But in A Day Like Any Other,the doings are given new depth; not only were the poets and the artists going to the Hamptons, but the Hamptons were a space of coordinated, open care.

Most centrally, after another breakdown and hospitalization, Schuyler moved in with Anne and Fairfield Porter, largely living in their Southampton home, but also traveling with the couple and their two children to Great Spruce Head Island in Maine. Schuyler had come for a “visit” in 1961 that lasted more than eleven years. Putting it that way may sound glib, and indeed when Kernan quotes Schuyler’s friends speaking about him and his illness, they might sound that way, too: when Schuyler wouldn’t or couldn’t leave the Porters’ house for more than a decade it was an intense, if not terrifying, experience for everyone involved. But on and off the page, they tended to treat the situation in little offhanded colloquialisms. That is, until they couldn’t.

Unlike other recollections of the New York School on which I was raised (not in family, but by many of the younger poets drawn to the protagonists of A Day Like Any Other who mentored me, themselves now almost all dead) or other biographies, this book gives us a lot of carefully managed absence. Kernan resists some of the most famous scenes from this time, simply because Schuyler was not there. Most painfully, the story of O’Hara’s funeral is faithfully rendered only in the secondhand that Schuyler had access to when the Porters told him about it, even though we know more or less what went down. Anne and Fairfield were worried that if Jimmy attended, it would cause him to have a break. Later, he would have visions of meeting with Frank perhaps occasioned as much by his exclusion from the funerary rites, and by the two’s falling out toward the end of Frank’s life, as by mental illness.

Kernan’s hand throughout is quiet, calm. The book took nearly three decades to complete, and yet its author, having completed it, remains willing to cede the floor to his subject, coordinating everything in service of his poetry and life story. Kernan’s job is to let us drop in on the poet at work, the resilient friend in need. This is achieved. Kernan was a friend of Schuyler’s in his last years, and had access to his other friends, their archives both formal and informal. Because Kernan did not set out to write a critical biography, the readings of the poems have a precise, constellating function, seldom blooming into full, formal analysis. Kernan instead offers us a kind of formulaic associative logic for how, where, and why the poems appear. And because Schuyler turned to poetry to make sense of his mind, his poems often take up the key moments that make up a life—what psychoanalysis might call sublimation. If, say, a fight with Schuyler’s mother is mentioned and Schuyler writes a poem about his mother (or you can substitute aunt, friend, experience), Kernan will produce it for us, even just a few lines.

Kernan calls this method of bringing the poem into the poet’s life “to restate what is self-apparent.”

The poems keep pace with the life anachronistically, and vice versa, even appearing before poems could appear, as in the sections on Schuyler’s boyhood. Delightfully, it’s as if the Collected Works of James Schuyler has been torn from its spine, lines cut out of individual poems and then reordered chronologically—not by when they were written, but by the moment of Schuyler’s life that needs the kind of elucidation that only a poem can offer. (I hope those who haven’t yet read Schuyler go read it in the way the poet intended, too). One of the moving impacts of this method is that some poems, like “The Morning of the Poem,” “Crystal Lithium,” and “Salute,” appear throughout.

Kernan, whose previous work assembling Schuyler’s diaries is put to good use here, understands that being present and working retrospectively are not in opposition, perhaps especially for Schuyler himself; today’s flowers will recall yesterday’s experience just as well as the analyst’s couch, which Schuyler had been making use of since the 1950s. Schuyler’s work, like that of O’Hara’s, can seem almost easy on the surface: he stared out a window and recorded what he saw. But in capturing the here and now he also moved backward in time, perfecting the art of observing and performing the work of memory (it didn’t hurt that often the window he was gazing out of was in his teenage bedroom, or at a friend’s house he had frequented for more than a decade).

What happens when we chronotag a line to the moment it is representing rather than the moment in which it was composed? This might seem like a perverse choice for writing about a poet who was famously presentist and, indeed, for many poets, this move would be deadly to their work, akin to the author who explains their poem so completely before they read it that the magic is gone by the time they do. In other words, selective sleight quoting could exacerbate the “I do this, I do that,” of the poem and the “he did this, he did that” of the biographical form. This is an even greater risk because Kernan mixes Schuyler’s lines with biographical narration and the recollections of other New York School poets who do indeed have a propensity to sound like how they write and write like how they sound.

But Schuyler, with Kernan stewarding him, triumphs. The chatty tone of Schuyler’s poems, like that of many of his contemporaries, can make it seem like that’s the extent of the work: talking. But the frequent, steep, precarious enjambment of the poet’s lines serves to constantly remind us that no one is talking at all. Schuyler’s ear for expressive meter and his freedom to break anywhere in syntax and thought takes any illusion of speech and reveals it to be pure line. The poems are fully formally and musically in control of themselves. So is Kernan as he represents the precariousness of Schuyler’s life and mind.

This method, which lets the dead poet speak for himself, is essential to how the book handles the thorniest thicket in Schuyler’s life and in his reception: his madness. Variously diagnosed as manic depressive, psychotic, and schizophrenic, Schuyler was in and out of hospitals for these conditions and for physical ones including diabetes and extensive treatment for third-degree burns acquired when he fell asleep smoking in bed.

Kernan deploys a light touch, remaining matter of fact when discussing Schuyler’s physical and mental states—his early religious visions, the tremor that appeared after Hart Island and then was exacerbated after his first serious boyfriend threatened, seriously, to kill him; his manias, his flights into psychosis. Kernan neither sensationalizes nor downplays what was true for the poet.

KERNAN OFFERS A SOBER MATERIAL ACCOUNTING of how the poet lived on a third of what he needed (accounting for his hospitalizations and medical bills) and how that remained possible through a network of fundraising, poets’ nonprofits, phone banking, friends’ grant writing, and writers’ emergency hospital funds. This is most pronounced in the period that followed the eviction from the Porters’ home—if not their lives (after the eleventh year, the Porters’ children had had enough). Kernan tells us who found Schuyler too much, too scary, stayed away, retreated some, downplayed his illness, came back to him, took advantage of him, and when and why. Twice, Schuyler’s friends called the cops on him. Sometimes he asked to go to the hospital, and it often seemed to help Schuyler; every time he went, his room became a gathering space for those who loved him. And those rooms always seemed to have windows; composing in those spaces, he was always on the inside looking out.

Schuyler’s eleven-year experiment of living with the Porters makes it clear that the New York School was not merely a set of geniuses who liked to hang out. They were committed to keeping Schuyler alive, tended to, and with his people, even when they felt they had run out of options and had to take unthinkable steps. They invented a kind of milieu therapy for themselves, just as it was being substantiated across the Atlantic in places like La Borde outside of Paris. The depth of care in his poet-milieu, care that was sent his way, is of a sort few among us are lucky to inspire and receive in the face of a system that had long decided it wanted him dead.

None of this is separate from his work. Again, Kernan has a needle to thread. Schuyler is presented as a poet whose sublimation was his life, his life the poem, and this rubs against a long-standing reading of Schuyler’s oeuvre—that he was basically downplaying his illness if not outright placid on the page. Shorn of complaint, his competent music becomes the sign of self-control in composition. Here, Kernan’s method of citing Schuyler allows the poet to speak for himself—a move that is radical for those with severe mental illness. We can’t know the feeling of that time, but Schuyler knew it and represented it for us.

Although few of his poems directly take on the subject of the ward directly, many were written there. So Kernan lets be what is so: Schuyler’s poems were part of his mania; he wrote some of his best poems from the hospital bed or after leaving it or just before landing in one by choice or by force. Someone else would glamorize it. Someone else would reduce the poems to merely products of touching God for a minute (Schuyler sometimes felt that he was Jesus, specifically the Infant Jesus of Prague) before medication kicked in. Kernan makes a different choice, and the book is all the better for it.

Kernan identifies a pattern that was part and parcel of Jimmy as he lived and Schuyler as he wrote: when he felt ecstatic, after properly meeting John and Frank for the first time, say, he became “manic.” This was his second breakdown; during hospitalization, Jimmy said he felt better “than I have in years.” Sometime during his nine-week stay in the hospital, Schuyler turned the evening that precipitated his breakdown into some poems, not as content, but in his lines and tones. Although his early work was “New York School” enough such that the Harvard boys recognized him (game sees game), now Schuyler began to emulate them deliberately, coming closer to them, especially O’Hara. The first of these poems, which became a standard across Schuyler’s nine readings at the end of his life, is “Salute.”

Past is past, and if one

remembers what one meant

to do and never did, is

not to have thought to do

enough? Like that gather-

ing of one of each I

planned, to gather one

of each kind of clover,

daisy, paintbrush that

grew in that field

the cabin stood in and

study them one afternoon

before they wilted. Past

is past. I salute

that various field.

Many think of Schuyler’s work as exuding a kind of evenness—as if meter should repel any and all association of madness to the poet who lived with it. That reading of Schuyler has never sat well with me and seems to rely on an idea that he doesn’t sound like other mad poets of his era, the ones who did time at McLean. Or that madness did not seem to alter his sensibilities. Put another way, because Schuyler’s poems don’t read as frenetic, and because Schuyler doesn’t conform to a received notion of the mad poet on the page,the mad states he could enter are assumed to be absent from the poems written in them.

Bringing those states back to a reading of Schuylerian syntax and severe enjambment, which “Salute” typifies, one can think of its line breaks as at once violent disruptions in syntactic business as usual and as signs that the sentence has continued on to face another day when we arrive at the next left margin. The poem itself is proof that he survived long enough to turn lived, painful experience into formal structure and rhythm. The line break represents the instability Schuyler kept going through. If this style is one of the two that Schuyler was most known for (the other, those neo-Whitmanian extended lines), both evince the struggle to keep going. It has taken Kernan’s book to show that the hospital and the milieu that helped Schuyler on either side of breakdowns were both constitutive of his work, without robbing the poet of an iota of dignity.

KERNAN SHOWS HOW THE SAFETY NET provided by Schuyler’s extended network slowly became unnecessary. At the end of his life, the poet started taking care of himself after meeting the right doctor, a young gay man named Dr. Newman who would later die of AIDS. Schuyler began managing his money; he kept the assistant position that his friends had put in place during the most difficult decade of his life, but the position actually became only that, bounded. His friendships with people like John Ashbery reflourished (although they had never been completely estranged). He started going to readings of friends like Barbara Guest. Always interested in younger poets, Schuyler started making magazines again, helping the next generation of writers influenced by the New York School (the Gizzi brothers come to mind). After more than ten applications, the poet was awarded a Guggenheim for both new poems and new fiction. He won a Pulitzer (Ashbery was on the committee, which rankled Schuyler slightly). He won a Whiting. He started to read his poems in public to packed audiences.

A Day Like Any Other opens with the infamous story of Jimmy’s reading for the first time in public at the Dia Center for the Arts in New York. To prepare for it, he had run two dress rehearsals, the first for younger poet friends who had cared for him and the second for those old beloveds, including Ashbery and Guest. If there is great pain in your friends being the only network that keeps you alive—no matter how bad the alternative—there is also some ecstasy in their watching you triumph. Schuyler’s Dia reading stands in for the “miracle” of this period.

The Dia reading was the first of nine (the last would be with Guest before Schuyler died in 1991 of a stroke and heart attack; another saw Schuyler fly to San Francisco, another was with Ashbery, the only time the two read together). The first time Kernan places it, it’s like reading a great party report from those who were there, including Eileen Myles (who served for a time as Schuyler’s assistant) and Ashbery. This telling centers on the standing ovation Schuyler received, a round of applause that was said to last minutes. Kernan presents it chorally, serially, with seemingly every poet the biographer could get his hands on telling us about it, reliving the story again, so that the prosody of the scene is matched by the extended collective holding of the applause. The second time, it appears chronologically. We learn that the applause lasted in reality for just under one minute. Everyone wanted it to be as long as Jimmy deserved. In memory they made it so.

Even here, many a biographer would go ahead and flatten Schuyler’s story to this familiar “miraculous” arc, especially if that biographer had been friends with him in this period. But Kernan is careful to tell it more like it was: these are the years of the AIDS crisis. Many beloveds of Schuyler’s were already dead, and scores more were dying now. Schuyler began to write, among his other modes, especially his love poems, elegies for those who were gone. As Jim Carroll once sang, being a poet sometimes feels like it’s just knowing the names of people who died, much like you know the names of flowers. In this way, even Schuyler’s triumph is remarkably depressive—which is to say not split off, not just good after ostensibly much bad. The truth of the poet’s life is unfurled in that admixture of ecstasy and pain it had always been, whatever the ratios. Here’s Jimmy in “Morning of the Poem”: “Die, die, die, and only pray the pain won’t be more than you can bear. But / What you must bear, you will.”

Hannah Zeavin is an associate professor of history at UC Berkeley. She is the author of The Distance Cure and Mother Media, and the founding editor of Parapraxis magazine.