LONG BEFORE ELON “I am become meme” Musk sought to dismantle the federal government under the aegis of a dog meme, there were LOLcats. Founded by two software developers in 2007, icanhascheezburger.com hosted an array of image macros, foraged from forums like Something Awful or created with an in-site tool, that paired a cute cat with a caption in misspelled or ungrammatical English, as in the site’s URL. Like the countless memes that would follow and like the forgotten ones that came before, a LOLcat isn’t much on its own. Derivative and communal, it accrues meaning through use. The real memes are the shares, upvotes, and modifications we make along the way.

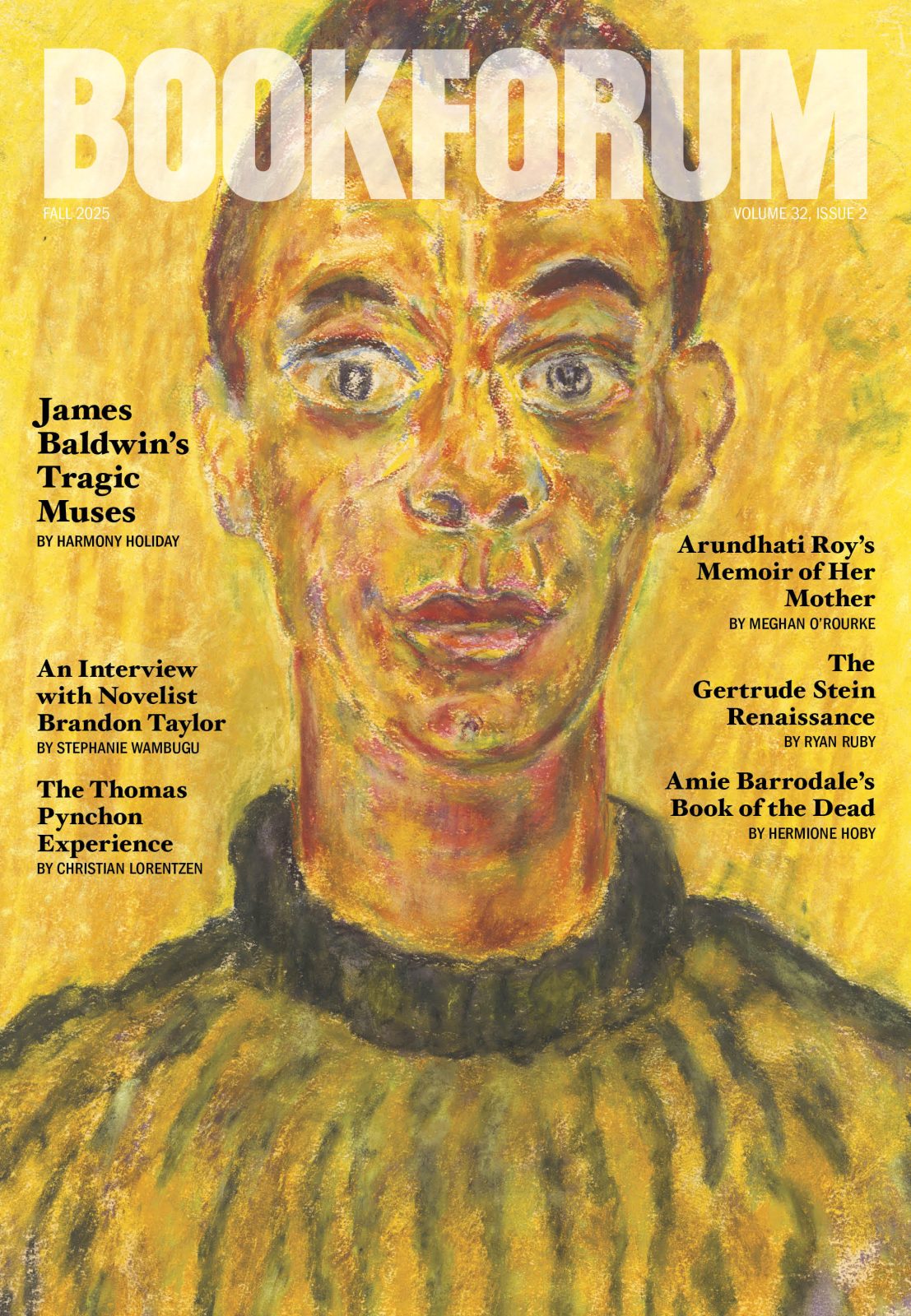

I Can Has Cheezburger, as the Dublin-based writer and multimedia artist Joanna Walsh reminds us, was an amateur project, an outlet for tech professionals who wanted an easier way to exchange cute cat pics after a hard day at work. In Amateurs!: How We Built Internet Culture and Why It Matters, Walsh documents how unpaid creative labor is the basis for almost everything that’s good (and much that’s bad) online, including the open-source code Linux, developed by Linus Torvalds when he was still in school (“just as a hobby, won’t be big and professional”), and even, in Walsh’s account, the World Wide Web itself. The platforms that emerged in the 2000s as “Web 2.0,” including Facebook, YouTube, Reddit, and Twitter, allowed anyone to experiment in a space that had been reserved for coders and hackers, making the internet interactive even for the inexpert and virtually unlimited in potential audience.

The explosion in amateur creativity that followed took many forms, from memes to tweeted one-liners to diaristic blogs to durational digital performances to sloppy Photoshops to the formal and informal taxonomic structures—wikis, neologisms, digitally native dialects—through which the categorization-pilled can go list-mode by catalog-maxxing. Even while it was an aesthetic and political promise—net art as the solution to the alienation of life under capitalism, the answer to the Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre’s avant-garde call to “Let everyday life become a work of art!”—user-generated content was also, at bottom, about the bottom line, a business model sold to us under the guise of artistic empowerment. Even referring to an anonymous amateur as a “user,” Walsh argues, cedes ground: these platforms are populated by producers, but their owners see us as, and turn us into, “helpless addicts.”

For some, online amateurism translated to professional success, a viral post earning an author a book deal, or a reputation as a top commenter leading to a staff writing job on a web publication. (Walsh, who has published thirteen books, describes herself as “one of the amateurs who made it” into the ranks of the at least semipros.) But for most, these days, participation in the online attention economy feels like a tax, or maybe a trickle of revenue, rather than free fun or a ticket to fame. The few remaining professionals in the arts and letters have felt pressured to supplement their full-time jobs with social media self-promotion, subscription newsletters, podcasts, and short-form video. On what was once called Twitter, users can pay, and sometimes get paid, to post with greater reach. The founders of I Can Has Cheezburger quickly became overwhelmed by the site’s popularity, and after only a few months online it was sold to the entrepreneur Ben Huh; it is now owned, along with the web encyclopedia knowyourmeme.com and several dozen other sites, by the holding company Cheezburger, Inc.

Readers in 2025, when artists who might once have been paid in exposure now prefer cryptocurrency, and when we read on our phones that no one is reading because of phones, may struggle to remember the optimism of the aughts, when the internet seemed to offer endless possibilities for virtual art and writing that was free at the point of production and consumption. The internet of Amateurs! is characterized by activity rather than passivity, Rickrolls and sly trolls rather than doomscrolls. Today, Walsh’s generation of intelligent artificers has been replaced by AI generations of shackled detainees in the style of Studio Ghibli. The content we do create online, if we still create, often feels unreflectively automatic: predictable quote-tweet dunks, prefabricated poses on Instagram, TikTok dances that hit their beats like clockwork, to say nothing of what’s literally thoughtlessly churned out by LLM-powered bots. Walsh wants us to remember how truly creative, and human, the internet once was.

Of course, even that human creativity could have an uncannily mechanical quality. As Walsh puts it, amateur aesthetic practice is “artifice that imitates artifice,” and memes, the basic unit of online culture, “teach us to expect the unexpected only in the context of what already exists.” As was the case with most literature composed before the Romantic era, what makes online textual artifacts like snowclones (Mad Libs–like verbal templates where words are swapped to humorous effect) and copypasta (recontextualized text reproduced verbatim, without citation) effective is their remixed unoriginality, their reanimated cliché. When Milton announced in Paradise Lost that he would do “things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme,” he was doing something that had very much already been attempted in rhyme, because the line is a literal translation from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, making it perhaps the first modern epic meme. In a way, the political power of Web 2.0, too, came from uncreative writing in a non-pejorative sense: the inventive coining of hashtags like #blacklivesmatter could only have material effect if they were repeated enough by others, the first-person pronoun of #MeToo made meaningful through collectivization, as intimate and impersonal as the generic lyric “I.”

AMATEURS! PROCEEDS THROUGH A NONLINEAR CHRONOLOGY, each chapter marked by a year, skipping around like a For You page: from 2007 (LOLcats) to 2011 (Tumblr) to 2001 (William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, recorded that year, later uploaded to YouTube) to 2023 (DALL-E image generation) to 2014 (selfies and autofiction) to 2020 (fan wikis) to 2015 (the confessional online personal essay). The chapters are bookended by an introduction on the early promise of 2004 and a coda on the defeat of 2025 and supplemented by an appendix with a straightforward timeline of the major events and publications that serve as the book’s touchstones.

Walsh, who has a PhD in critical and creative writing and a suite of accolades and appointments but not a permanent university job, describes her own approach to the aesthetic theory of the internet as “amateur,” a word rooted in love, or as prefixed by the “para-” that denotes the unseriousness of so much online activity: para-academic, parasocial, the parataxis of one thing after another sliding past us on our infinite scroll, to the side of the sanctioned, sometimes earning side-eye. In its collection and reproduction of resonant online and offline phenomena and references, Amateurs! is structured like the internet, “like” being the operative word and the basis, Walsh argues, of aesthetic experience online. Online amateurism involves curating things we like, including by clicking “like,” and artful posting on social media often relies on surprising similitude: visual puns such as a bar graph resembling the graphic silhouette of Saddam Hussein in his hiding place, or a series of four images that echo the four panels of a canonical web comic, can garner hundreds of thousands of likes. Memes, as is etymologically encoded in the word itself, function mimetically. NFTs failed by trying to endow with singular aura what only has value through reproducibility. We like what’s like. According to Aesthetics Wiki, the primary subject of one of Walsh’s chapters, the suffix “-core,” as in cottagecore, evolved, meme-like, from “cœur”: go ahead and smash that heart button.

Amateurs! is also like the internet in its juxtaposition of the high (as in high theory) and the low (as in LOLcats). Sometimes this evokes the textual tension of a meme, an enjoyable friction between content and form, the zeugmatic yoking of disparate terms as in the Google-search-derived flarf poetry that flourished in the 2000s, the free association of a blog, the discord of a social media feed, ideas “hyperlinked” together, the self-conscious lack of rigor made into its own methodology.

Sometimes, though, it feels more like a specific meme, the one where under the caption “Leftist memes be like” lies an ocean of text in a microscopic font, a treatise where a snappy phrase should do. Some juxtapositions can feel embarrassing, even cringe, as when we’re told that “like poetry, fandom relies, as the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth wrote, on a ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.’” (Real Wordsworth heads know that the rest of the sentence Walsh cites rather restrains the part she quotes: “but though this be true, Poems to which any value can be attached, were never produced on any variety of subjects but by a man who being possessed of more than usual organic sensibility had also thought long and deeply.”) Foucault and Ricoeur are recruited as authoritative authors to make the point that memes, rather obviously, are authorless. This crowded theoretical field, too, can mimic parts of online experience. One of the pleasures of scrolling Twitter, the cacophonous dissonance of different voices jostling together, is also what makes it maddening, which I could but don’t think I need to back up with a quote from Freud, Lacan, or Derrida. In one of several passages where Walsh rehearses Kant’s Critique of Judgment, the final clause hits like an unintentional punch line:

Both the “concept-based explanation” and the para-epistemophilic feeling are necessary to Kant’s categorisation of an experience as aesthetic: “If art merely performs the acts that are required to make a possible object actual, adequately to our cognition of that object, then it is mechanical art; but if what it intends directly is [to arouse] the feeling of pleasure, then it is called aesthetic art.” Kant goes one further: it “is agreeable art if its purpose is that the pleasure should accompany presentations that are mere sensations; it is fine art if its purpose is that the pleasure should accompany presentations that are ways of cognizing,” something that Know Your Meme’s multilayered expression gets perfectly.

A website like Know Your Meme is not outside the purview of even the most serious aesthetic theory, which can approach artifacts of mass culture with similar eclecticism; the University of Chicago professor Sianne Ngai, frequently cited in this book and one of the most prominent living humanities academics, brings Adorno, Facebook, Nietzsche, 1970s performance art, and early modern commedia dell’arte to bear on Jim Carrey’s performance in The Cable Guy. The problem isn’t that Walsh, who describes amateurism as “a matter of imitation,” merely mimes professionals like Ngai; it’s that the imitation game isn’t fun. Walsh summons smart-sounding support for a claim like an academic aiming to impress a peer reviewer rather than helping the reader see, like a good fan account, why the Kant quotes are worth savoring, and not just something to scroll past.

Playful and illuminating apposition can easily devolve into “i wrote about white boy summer, cheugy, going beast mode, bestie, do you ever get lonely, the moon, and what it all means for marxism in the new issue of hit the back walls journal of poetry and poetics,” as the novelist and amateur shitposter Sebastian Castillo parodically tweeted. (If you need a definition of “parody,” Amateurs! obliges: “As Judith Butler wrote in their 1998 essay ‘Merely Cultural,’ parody is what ‘could not have happened if there were not this prior affiliation and intimacy, and that to enter into parody is to enter into a relationship of both desire and ambivalence.’”) The book’s mashing together of aesthetic autonomy and Autostraddle, or the Freudian theory of screen memories and something Walsh remembers seeing on her screen, works best as a kind of scrapbook, of which the mixed-media tumblelogs of Walsh’s fascination are skeuomorphs. But the failure of a point to land doesn’t offer the same delights as the failure of a tweet’s language to conform to standard English, or the failure of a meme to make sense.

THE ONLINE SPACES where amateur content creators once “created and steered online culture” have been hollowed out and replaced by slop, but what really hurts is that the slop is being produced by bots trained on precisely that amateur content. Bricoleurs make art out of trash; AI is a machine for turning art into trash. The deal was, Walsh reminds us, that we would pay for the privilege of creating free content with our data; we didn’t realize we’d be paying with our creativity. The inherent recyclability of memes doesn’t feel as liberatory from the bourgeois cult of subjectivity when artistic work is getting cropped and reposted by engagement-farming accounts, or by a multibillionaire whose greatest losing investment has been a massive expenditure of time and energy trying to get people to think he’s funny. Recently, a self-described “memelord” announced on X that he had landed unpaid gig work for Andrew Cuomo’s mayoral campaign by pitching memes as stupidly effective. (Later tweets suggested this was an attempt to promote his business, “an AI-based meme generation platform.”) Dead internet theory—the idea that a substantial percentage of information exchange online is bot-to-bot—might not be so depressing if there weren’t also so many humans who have willingly given up their own humanity or tried to squeeze it out of others. As one worker in the AI art mines is quoted in a newspaper interview, requoted by the artist and essayist Hito Steyerl and requoted again by Walsh, this technology doesn’t so much replace people with robots as the other way around: it makes “people like me work like robots.”

In her 2020 novel Mercury Retrograde, set in 2014–15, the artist and brand strategist Emily Segal writes, “With the rise of trolling culture and the collapse of free speech between then and now, it seems kind of insane to think that letting the voices of the Internet scribble all over everything would be anything other than an endless mandala of swastikas and jizz, but that’s how optimistic I was at the time.” Segal’s novelis an infrathinly veiled account of her time working as the creative director of genius.com, a tech start-up that began in 2009 as a crowd-sourced explainer of rap lyrics but with the “Talmudic” aim, as one founder put it, of annotating the entire internet. “I saw it as a chance to write on the membrane of reality itself,” Segal’s autofictional avatar says by way of explaining why she took the job; she needed the money, but she also thought she could make something meaningful. Like Segal, and like Walsh, I was once optimistic about what could happen at the intersection of art and technology in the years before “at the intersection of art and technology” became a snowclone. “Memes—the kinds clients hoped they could pay me to create—were narratives with no structure, no climax, and no resolution,” Segal’s narrator reflects, which made me think of other things memes were like: certain Renaissance sonnet sequences; Jerry Lewis movies; love.

Katie Kadue teaches English at SUNY Binghamton.