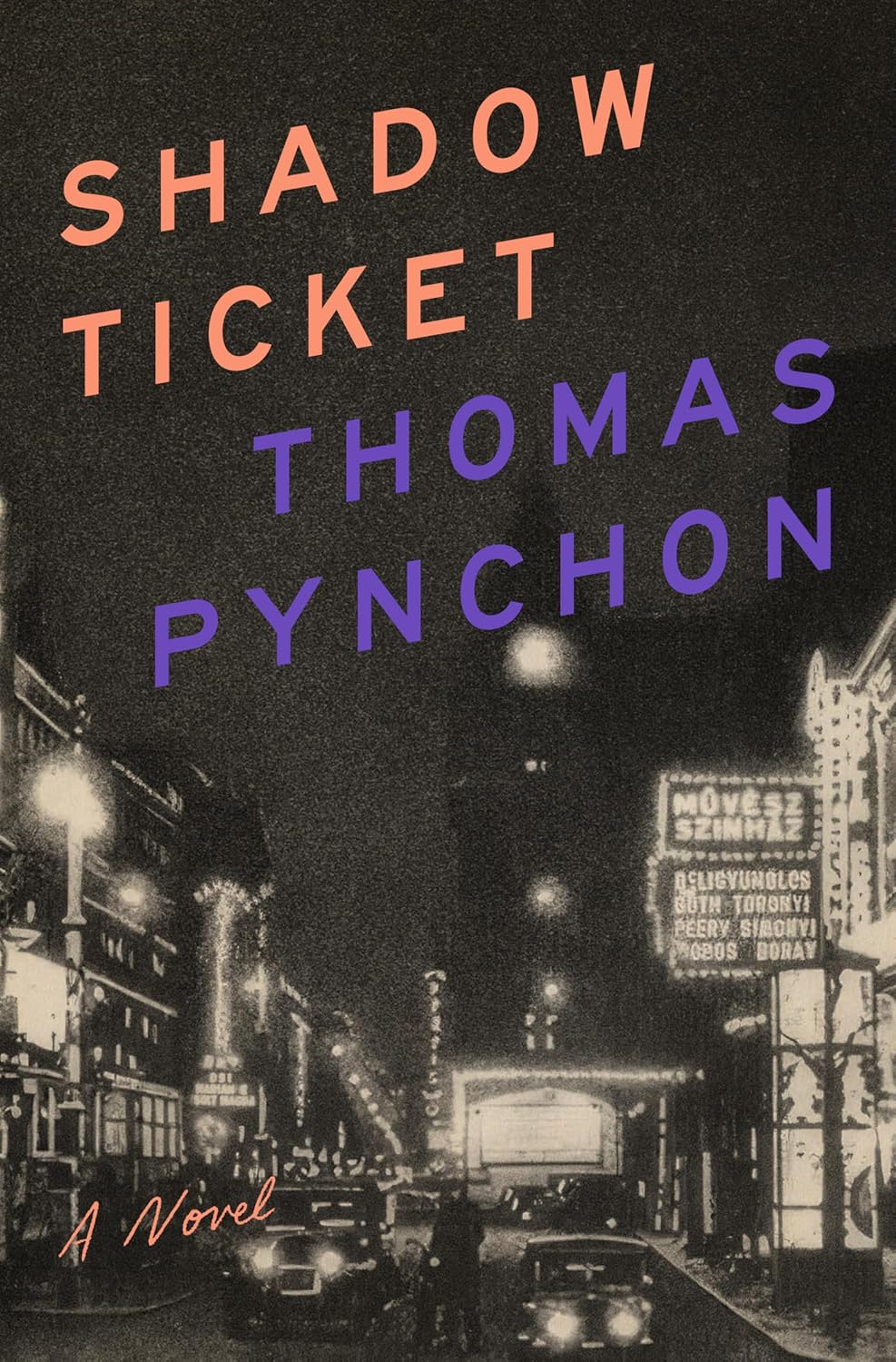

THE PATERNITY OF Hicks McTaggart—defender of dames, dodger of bombs, twirler of spaghetti, the amiable behemoth hero of Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket who prowls the streets of Depression-era Milwaukee—is a question his author leaves open. His mother, Grace, and her sister, Peony, “grew up in the Driftless Area, a patch of Wisconsin never visited by glaciers, so that its terrain tends to be a little less flat and ground down than the rest of the state, free of the rubble, known as drift, that glaciers leave behind.” (Despite its charming name, the Driftless Area is a real place, not a Pynchonian invention.) Once old enough to hitchhike (“Soon as they could figure out how to bring their thumbs out of their mouths and into the wind”), Grace and Peony started consorting with circus performers wintering in Baraboo, a town at the Driftless Area’s northeastern edge, before making their way to Milwaukee to take ordinary jobs and marry ordinary men. Grace’s marriage to Eddie McTaggart was interrupted by the discovery of her ongoing affair with Max, a German elephant trainer back in Baraboo. Eddie skipped town and headed west, never to be heard from again. Of Max we are told: “When other boys got sentimental they talked about all the children you were going to have, with Max it was more likely to be elephants.”

Whoever his father, Hicks is not unlike an elephant: large and powerful but gentle by nature and with a memory that keeps leading him down nostalgic pathways, a heartbreaking quality since his story will fling him far from home and offer no way back. A good memory is an asset for a private detective, charged at the start of the novel with finding a missing cheese heiress named Daphne Airmont. Gumshoeing is the more humane line of work Hicks took up after an apprenticeship as a strikebreaker for hire. He had been an accidental corporate thug since the job seemed merely a “logical” extension of high school in Milwaukee. “It didn’t get as political for Hicks as it did for some,” Pynchon writes. He didn’t know what the word “Bolshevik” meant and figured he was just beating up Polish guys as usual, only now for money. One day a short bespectacled striker taunts him: “The famous Muscles McTaggart, ain’t it. Why you’re nothing but a big creampuff, what happened to you? you were the wrath of god once, part of history, what is it, your mother’s been yellin at you?” After the “truculent little Bolshevik” slips away from a backhand delivered in a state “angry enough to finish off the four-eyed troublemaker and leave the body where it fell,” Hicks experiences “relief at not having killed somebody.”

Our hero is a convert, a recovering agent of reaction who turns into something of a rescue artist, which is not a bad thing to be at a time, 1932, when there are Nazis lurking everywhere and few are aware of just how evil they’ll become. Hicks’s own Uncle Lefty (full name: Detlef Flascher), who raised him with Aunt Peony after his folks split, has some sympathies of his own. “Der Fuhrer,” he says, “is der future, Hicks. Just the other day the Journal calls him ‘that intelligent young German Fascist.” He goes on:

“You can’t trust the newsreels, you only think you’ve seen him, the Jews who control the movie business only allow footage that will make him look crazy or comical, funny little guy, funny little walk, funny mustache, German Charlie Chaplin, how serious could he be? But there also exist other Hitler movies, yes, some even filmed in color, home movies, a warmer, gayer Hitler, impulsive, unorthodox, says whatever comes through his head, what’s wrong with that?”

“Jumpin up and down all nutty and screaming the minute anybody brings up the topic of Jews, sure everybody’s welcome to their own sense of humor. Swell casserole here, by the way.”

Hicks, we’re reminded over and over again in this novel full of food gags, enjoys a good meal. He tends not to get too excited, and in the roll call of Pynchon’s characters—among them the lovable slobs like Pig Bodine, Pirate Prentice, Tyrone Slothrop, Zoyd Wheeler, and Doc Sportello, not to mention the “human yo-yo” Benny Profane—he might be the one who most resembles Homer Simpson. As the algorithms often remind us, when Pynchon voiced the character Thomas Pynchon, a famous author with a paper bag over his head eating chicken wings, on a 2004 episode of The Simpsons, he deleted the line “No wonder Homer is such a fat ass” and scrawled a note explaining, “Sorry, guys, Homer is my role model and I can’t speak ill of him.” Hicks is a burly guy with an air of innocence about him. Is it of any significance that he shares the surname of the English Hegelian philosopher J. M. E. McTaggart, whose most famous theory concerns “the unreality of time”? It may be too soon to tell. And though I can’t be sure of Hicks’s paternity, I have a hunch that one of his sidekicks, Skeet Wheeler, a street urchin who tips him off to the goings-on of the Milwaukee underground and informs him in a letter at the end of the novel that he’s moving to California, is the father of Zoyd Wheeler, the hero of Vineland.

Pynchon is now eighty-eight years old, and news this summer of his new novel was greeted with delight, coming as it did on the heels of a second Paul Thomas Anderson adaptation of one of his novels. (One Battle After Another, based on Vineland, was not yet screening in New York as I was finishing this review, but the murmurs from Los Angeles were almost troublingly ecstatic.) Along with Don DeLillo, he survives as one of the granddaddies of the paranoid systems novel, and we are unlikely to read many or any more new novels from the pair. (Pynchon is of course the grandparent we’ve never laid eyes on, aside from the famous yearbook pictures, and know only from his words and the legends and rumors: Did he really serve as a crossing guard at his son’s school on the Upper West Side? Does he actually appear in a few frames of Anderson’s adaptation of Inherent Vice? Is that him with Richard Fariña and Joan Baez seeing Dylan go electric at Newport in 1965? As with DeLillo’s last (by which I mean most recent) book, The Silence, there is a temptation to call Shadow Ticket a work of “late style” and point to certain economies of style evident in the swiftness of transitions, the plunging into familiar perennial themes, a certain doing away with gratuitous niceties in favor of something like playing new, pared-down versions of the greatest hits as if in medley form.

These characterizations aren’t wrong, but I don’t find them very illuminating. Shadow Ticket is first of all a very funny book. (Call me crazy but I think the same was true and underappreciated in the case of The Silence: an esteemed old man muttering football play-by-play commentary from memory in a Manhattan apartment on Super Bowl Sunday when the power has gone out all over America while his protégé is in the next room cuckolding him—that’s funny stuff.) There’s a high ratio of gags per page, which is nothing new for Pynchon. And there’s a beautiful casual lyricism to the narration (see those thumbs of Hicks’s mother and aunt going from their mouths to the wind) offset by the often dopey dialogue between Hicks and the lowlifes he meets in Milwaukee and the more sophisticated snoops and spooks he comes across on the other side of the Atlantic. (You can hear the condescension in their voices, especially a pair of English intelligence agents who work for MI3b.) In Shadow Ticket, the set pieces don’t go on as long as they used to, the Manichaean divide between the good and the evil isn’t as stark as it used to be, even as recently as in Bleeding Edge, Pynchon’s 2013 novel of New York City before and after 9/11, because 1932 is a stage in the interzone before the real evils, ideological and technological, really dug in their heels. Even the FBI doesn’t have its repressive act together yet. If a former young thug like Hicks can be saved, there’s time for Uncle Lefty, or for any goon who still has a heart.

I will be surprised if Shadow Ticket, a sentimental slapstick adventure novel, nostalgic to the point of gooeyness but never quite crossing over into the corny, a soft-boiled noir including a few too many jokes about cheese, isn’t met with general acclaim by reviewers. It wasn’t always the way. I’m old enough to have worked as a deckhand at a magazine where a critic gave up reading Against the Day out of exhaustion if not quite disgust and then had the temerity to admit it in print. Reviewing pages have been thinned by the forces of history and technology; few Pynchon skeptics anymore bother to take the time to read the novels and register their objections. Right-wing literary pages where these broadsides found a welcome home hardly exist today, and to the extent that they do they are probably as open to Pynchon’s fiction as they are to anything familiar if once radical that now counts as Americana. Pynchon had his admirers in the establishment from the start: in 1963 George Plimpton called V. “a brilliant and turbulent novel” by “a young writer of staggering promise.” Pynchon’s most authoritative, perceptive, and insightful defender and interpreter was Richard Poirier, who took to the pages of the London Review of Books in 1985 to reject the criticisms of the juvenilia collected in Slow Learner lodged by the author himself in his introduction. Writing in the Saturday Review on Gravity’s Rainbow in 1973, he argued: “Readers who get impatient with this book will most likely be too exclusively literary in their responses rather than not literary enough. They’ll stare at designs without listening to voices, wonder about characters when they should be laughing at grotesques, and generally miss the experience in a search for the meaning.” Oh, meaning, that silly thing, forget about it.

But he’s right: then as now with Pynchon, the experience is the thing. The meanings are there, but they are overloaded in the prose, and the prose propels you past them like the speeding motorcycles that zoom through much of the last third of this novel, describing the circumference of “Hungary Unredeemed,” an unholy rally of irredentists, communists, fascists, fathers, daughters, and robots. Praising Against the Day in 2007, Michael Wood remarked that more impressive than the maintenance of his privacy was the fact that Pynchon had “created a career impervious to narrative,” and at the time it was true. Nothing before it suggested the outpouring of Gravity’s Rainbow and the same could be said of Mason & Dixon and Against the Day. The three novels that have followed since have had detective protagonists, and though simpler and somewhat more conventional than the doorstoppers that preceded them, they throw back beams of light on themes that have animated Pynchon’s work since Plimpton correctly identified V. as a picaresque: quest, investigation, the possibility of redemption. Oedipa Maas was a detective too.

Once upon a time Joan Didion and Gore Vidal counted among Pynchon’s skeptics. In a 1965 National Review column that ran under the headline “Questions About the New Fiction,” she took aim at Pynchon and Joseph Heller, among others:

the hallmark of this kind of fiction is its refusal to follow or think out the consequences, let alone take them; it is content to throw up its hands, cry that outrage surrounds us. This absence of moral toughness seems to me to determine the style and the structure of the novels, or rather the lack of it. To throw a picaresque character into a series of improvised situations is to stay as clear of a consistent point of view as one possibly can; all the old structural conventions automatically confer upon the novelist, whether he wants it or not, a point of view, a stance, a statement—just as the mechanical tensions of film do.

You can imagine the Pynchon of the Slow Learner introduction nodding his head in agreement with this assessment, one that anyway doesn’t apply to his books that followed it, in which more and more a consistent authorial point of view is unmistakable, in which consequences are certainly followed and thought through, all the way to the end of the rocket’s arc. What might seem like improvisation is always an illusion, and as for structure he has been a master of the art since he put the structure of his first novel in its very title. As for moral toughness, his is that of the stridently sentimental liberal, one who prizes privacy, freedom, and play above all.

Vidal was a more sympathetic skeptic in his 1976 essay on “the New Fiction,” “American Plastic,” in which he admitted to finding Pynchon’s use of metaphors from physics exhilarating. His harshest complaints were on matters of style: “To my ear, the prose is pretty bad, full of all the rattle and buzz that were in the air when the author was growing up, an era in which only the television commercial was demonically acquiring energy, leaked to it by a declining Western civilization.” And he tilted at those moments when Pynchon’s characters break into original songs: “Pynchon’s prose rattles on and on, broken by occasional lengthy songs every bit as bad, lyrically, as those of Bob Dylan.” A generation gap of another kind was still in effect. No readers are still alive who weren’t raised on or at least in the aftermath of television. And sure, the jingles, like the comic books and the pop songs, leave their traces in the prose. In Vineland especially, Pynchon is aware of the vices of the tube as an appliance of control. But I suspect that the medium’s main effect on him in his youth was to deliver the movies of the 1930s as Pauline Kael wrote in her 1967 essay about film on television: “Everything is in hopeless disorder, and that is the way new generations experience our movie past.” Pynchon was a member of the first of those generations, like those slightly younger than him who made the films of the New Hollywood, now all taking their last laps themselves. The names Myrna Loy, Bela Lugosi, James Cagney, and Chaplin flicker through Shadow Ticket along with the antic spirit of early-’30s Hollywood, one of Pynchon’s lost anarchic utopias before the imposition of codes and the tyranny of accountants.

James Wood has over the years found in Pynchon his ultimate antagonist, Against the Day arriving as if to fulfill his critical prophesies about hysterical realism. In a review both relentless and punctuated by qualifications about its subject’s humor, knowledge, and talent—“Many things can be said against this writer, but no one has ever accused him of lacking talent. (It may be that he has too much.)”—Wood swings a wrecking ball at an entire wing of the tradition of the English novel, that of Henry Fielding, and calls Against the Day “a salad of buoyant despair.” I might have chosen a different food metaphor, like an ice cream sundae, but we return again to Poirier’s distinction between reading for meaning and reading for the experience. For Wood, the experience of reading Pynchon is a joyless one: he sees him as an avant-gardist of content but not of form. “One of the problems with hysterical realism, of which this novel is a kind of zany Baedeker,” he writes, “is that one suffers both the hysteria and the realism: the worst of both worlds. There is the weightless excess, the incredibilities, the boredom that always attends upon cartoonish, inauthentic novelistic activity. But there is also the boredom attendant upon the rather old-fashioned, straightforward realism used to create this very escape from realism.”

In his criticism of Pynchon, Wood strikes me as a man consistently laughing while also insisting that his laughter is the wrong sort of laughter. And it is true that there are limits to pastiche and that if there are orders of pleasure, pastiche doesn’t occupy the highest rung. The young woman Hicks McTaggart is chasing, from Milwaukee to Budapest, is the heiress to a fortune earned from the success of a “once infamous food product known as Radio-Cheez.” A competitor to Kraft’s Velveeta, “Radio-Cheez was designed to stay fresh forever, in or out of the icebox, thanks to a secret, indeed obsessionally proprietary, radioactive ingredient.” After the “federal Food and Drug killjoys” banned the stuff for being “‘harmful to human health’ somehow,” it also turned out to be spontaneously explosive,

sending once loyal customers running in blind panic down to nearby rivers to throw in all their as yet unexploded jars of the product, which were then carried away buoyant and glowing downstream sometimes hundreds even thousands of miles to coastal harbors and ports before detonating against the hulls of ships at anchor, any found still upstream being promptly labeled enemy mines, with duly sworn sharpshooters ordered to fire at them from a safe distance. Fish in the rivers and harbors were briefly puzzled by the bright new scatter of food potential until deciding, all together the way fish do, that they didn’t care for Radio-Cheez either.

How seriously can you take a book built from such a premise? It’s a joke that radiates through the rest of the novel, its plot, such as it is, hinging on the reunion of Daphne Airmont with her father, Bruno, the so-called “Al Capone of Cheese.” He will hand over to Daphne the secrets of the International Cheese Syndicate, locked in a vault under a remote Swiss mountain range, enough dirt to “send the whole business up in one giant fondoozical cataclysm.” It is as if Oedipa Maas were granted the uncensored history of the secret Tristero just before the end of The Crying of Lot 49 (and perhaps after its last sentence she is). And what to make of the news delivered to our Milwaukee exiles that a revolution set off among Wisconsin dairy farmers intent on raising the price of milk has resulted in a coup unseating Roosevelt and putting General Douglas MacArthur in charge of the nation? Are all the Nazis running around this novel brownshirted harbingers not of the nightmare we know but of an American Reich, and all because of some spilled milk?

Contra Gore Vidal, I have always thought Bob Dylan’s lyrics superior to the ditties Pynchon puts in his books (which the author himself called “stupid” in the flap copy for Against the Day), but at this late date in their life cycles a comparison seems appropriate. Both men emerged in the early ’60s with revolutionary designs on their art forms; both have been inscrutable tricksters, alternately eliciting critical adoration and spite; both have been mistaken for prophets or Judases; both have shown us the America we know and suggested the existence of Americas, ones either more sinister or more perfect than the Union we inhabit. No circus stays in town forever, and some comets never come back.

Christian Lorentzen is a writer living in New York.