DESPITE HER REPUTATION as a long-winded writer, Gertrude Stein had a talent for pithiness. Of Oakland, the town where she grew up, she famously remarked: “There is no there, there.” Of one of her literary nemeses, Ezra Pound: “A village explainer, excellent if you were a village, but if not, not.” Of the younger American expat writers who flocked to Paris during the ’20s: “You are all a lost generation.” Of the atomic age: “Everyone gets so much information all day long that they lose their common sense.” Of pithy remarks: “Remarks are not literature.”

According to Alice B. Toklas, the woman who had for forty years served as her devoted secretary, editor, cook, bouncer, companion, and lover—as well as the narrator of her most famous book—Stein kept her wits and her wit to the very end. On July 27, 1946, the two waited in a hospital in a suburb of Paris, where Stein, who was suffering from stomach cancer, would undergo the surgery that would kill her. Toklas recalls: “I sat next to her and she said to me in the early afternoon, What is the answer? I was silent. In that case, she said, what is the question?”

Stein’s obituarists seemed to know exactly what the question was. Starting that evening, Eastern Standard Time, The New York Times wire service set the tone. The “famed woman writer” was “one of the most controversial figures in American letters.” The controversy was this: “Devotees of her cult professed to find her restoring a pristine freshness and rhythm to language. Medical authorities compared her effusions to the rantings of the insane.” In the days that followed, other newspapers adopted the same framing. According to one, “Her admirers held that she wrote the most profound prose of the twentieth century; others, who did not pretend to understand her books, said she wrote gibberish.” Another claimed that “in some she stimulated a fierce, undying admiration; others looked on her as an amusing poseur and a charlatan.” Who was right? The obituarist punted: “History alone will judge.”

Almost eighty years later, the court is still in session, though the debate is now conducted in less spicy language. On the conventional understanding, there are in fact two Steins: a writer’s writer and a bestselling celebrity memoirist. It is only the first who remains controversial. To give a fairly accurate picture of their respective reputations we need only look at who publishes her books today. Three Lives and The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas are Penguin Modern Classics. They are also included, along with her unpublished first novel Q.E.D. and Tender Buttons, in Gertrude Stein: Writings 1903–1932, the first of two Library of America editions of her work, the closest thing American literature has to the French Pléiade in signaling canonicity. Not included, however, is The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress, which was completed in 1911 and first published in 1925. Stein considered the thousand-page-long epic of the Dehning family, the Hersland family, and indeed “everyone who ever was or is or will be living” her masterpiece, and the primary evidence for her boast that she was “the creative living mind of the century.” Today, it is published by Dalkey Archive Press, home of the unreconstructed avant-garde. Its influence is as undeniable as it is unacknowledged. As Stein put it: “the followers are always accepted before the person who made the revolution.”

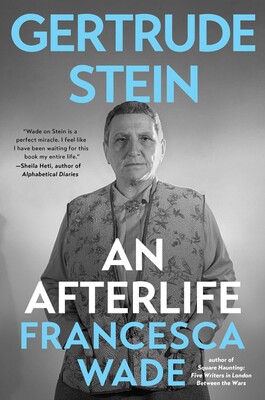

THE LATEST WITNESS to testify for the defense is the biographer Francesca Wade, whose Baillie Gifford Prize–nominated Square Haunting, a group portrait of five female writers who lived on London’s Mecklenburgh Square between the wars, was published in 2020. Reflecting on her craft, she writes: “Biography, like detective fiction, tends to begin with a corpse.” But in her new biography of Stein, Wade puts the corpse in the middle.

Bookended by a prologue, in which Wade describes how she came to be interested in Stein, and an epilogue, in which she makes a pilgrimage to Stein and Toklas’s country home in Bilignin, France, Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife is divided into two parts. The first, “Life,” contains the events that have become the stuff of literary legend: Stein’s student years at Radcliffe under the supervision of William James; her expatriation to Paris with her beloved older brother Leo, an art collector and dilettante; her courtship of Toklas, which ultimately precipitated dramatic fallings-out with Leo and others; her friendship and artistic collaboration with Picasso; her years of literary struggle and experiment culminating in the writing of Three Lives, The Making of Americans, and Tender Buttons; her role as a volunteer driver in World War I; her salon on 27 Rue de Fleurus during the Roaring Twenties; her breakthrough to international celebrity with the publication of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas; and the dangerous and politically controversial years in Bilignin during World War II that she recorded in Wars I Have Seen, the best-selling book of her career.

The second part, “Afterlife,” tells a tale that will be less familiar to those with only a casual interest in Stein. Centered on the widowed Toklas, it concerns the writing of her infamous cookbook and her late conversion to Catholicism—so that, as she touchingly believed, she could spend her own afterlife with Stein—as well as her unflagging efforts to manage Stein’s estate, her papers, her historic art collection, and her legacy with the help of the couple’s trusted friend, the writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten. In this last capacity, Toklas proved to be as implacable a gatekeeper as she was during her days controlling the door to the Rue de Fleurus. The most significant of the handful of strangers she spoke to was Leon Katz, a doctoral candidate at Columbia. Katz began visiting the Stein collection at Yale shortly after her death, transcribing material from the period leading up to the writing of The Making of Americans, including correspondence, early drafts, and notebooks that contained diagrams charting out the personalities of everyone she knew, including Toklas. Between November 1952 and February 1953, he interviewed Toklas and recorded her candid impressions and memories of that time for his dissertation “The First Making of The Making of Americans.” In what, even by grad school standards, would be considered an acute case of procrastination, Katz took ten years to publish his dissertation. He refused to let anyone see the notebooks of his interviews with Toklas, which he said he needed for his forthcoming book-length study of Stein. The notebooks became the holy grail of Stein scholarship. The study never appeared.

Wade’s subtle departure from biographical convention in Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife allows her to reveal particular pieces of information about Stein not when they occur but as they are discovered afterward. Take, for example, the story behind Stein’s book of poetry Stanzas in Meditation, which was written in the months before Stein turned to work on the Autobiography but was only published posthumously. In “Life,” the Stanzas are largely passed over in silence; but in “Afterlife,” Wade reveals that Toklas, who was responsible for typing up everything Stein wrote, crossed out each instance of the word “may” in the manuscript and replaced it with “can.” Why? In a moment of hermeneutic inspiration, Stein scholar Ulla E. Dydo, author of Gertrude Stein: The Language That Rises 1923–1934, guessed that Toklas’s strange editorial intervention might have a biographical basis. As Stein was trying to find a publisher who would rerelease The Making of Americans, she and Toklas found the manuscript of her unpublished first novel, Q.E.D., which describes a love affair with a young woman called Helen, based on May Bookstaver, a fellow student at Radcliffe. Working off a hint from Katz, Wade tells us, Dydo concluded that Toklas cut all the “mays” from Stein’s manuscript. Behind the official explanation for the Autobiography—after years of neglect by the public, Stein wanted to write a commercially successful book—there was another, more intimate one: Stein was trying to save her relationship.

On top of the drama created by moments like these, the structure of Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife allows its readers to understand something that usually goes unmentioned in literary biographies. A writer is not merely the sum total of known events that occurred to her between birth and death, she is also the network of readers created by her work during that period and afterward. This network includes, among others, artists, journalists, scholars, archivists, and, yes, biographers, who shape our sense of who the writer is and what their writing means. To write a biography is not merely to record a person’s life in some neutral, external way; it is, in effect, to participate in it.

THE IMMEDIATE PREDECESSOR to Wade’s biography is the late journalist Janet Malcolm’s 2007 Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice. Like Wade, Malcolm gives Stein and Toklas equal billing, on the understanding that the works that bear Stein’s name were produced to an unusual degree by more than one person. As a “caustic dissector of scholarly intrigues,” in Wade’s words, Malcolm would probably have also endorsed her conception of the biographer as a kind of detective. After all, much of Two Lives is taken up by Malcolm’s sleuthing, as she assembles a crack team of aging Stein scholars—Dydo, along with Edward Burns and William Rice—to help her persuade Katz to show her the notebook containing the transcripts of his conversation with Toklas, a story she was responsible for breaking to the general public. Although she is ultimately unsuccessful, the author of The Journalist and the Murderer makes reflections-on-process lemonade out of the lemon of Katz’s refusal to meet with her.

Afterlife has a few built-in advantages over Two Lives. The first is access to information. After Katz’s death in 2017, his papers, including the elusive notebook, were sold to the Beinecke Library at Yale, where they joined the rest of Stein’s archive; Wade was the first person to consult it, and to incorporate Katz’s notes into her research. The second is page count. Conceived of as a biography from the start, Wade’s book is nearly twice the size of Malcolm’s, which was pieced together from a pair of articles Malcolm wrote for The New Yorker in 2005 and 2006. Where Malcolm often merely mentions a fact about Stein or retells an anecdote from her life, Wade has the space at her disposal to situate it in a narrative and provide context for it. This is particularly important when it comes to their respective interpretations of Stein’s and Toklas’s relationship to their Jewish heritage, Stein’s proposed translation of the speeches of the Nazi-puppet Maréchal Pétain, their close friendship with the nefarious Vichy official and collaborator Bernard Fäy, and the biographical mystery—with which, aside from the fate of Katz’s notebook, Two Lives is narrowly concerned—of how two well-known, Jewish-American lesbians survived the Nazi Occupation.

But the fundamental difference between the two biographies is their authors’ attitude toward their subject. Malcolm can barely conceal her animus toward Stein as a person, an animus that extends not merely to her politics, but to much of her writing as well. Malcolm prefers her popular writing to the experimental work. She has to be shamed by Dydo into reading The Making of Americans, on the quite reasonable grounds that anyone writing about Stein should at least have finished her masterpiece. Even then, reading the “innately rebarbative” novel is clearly a chore for her. Malcolm writes: “The Making of Americans was a work that Stein evidently had to get out of her system—almost like a person having to vomit—before she could become the Gertrude Stein as we know her.”

There is, of course, no rule that says that a literary biographer must approve of their subject’s character, find their personality appealing, or even admire all their writing, though the irony in the latter case is that if you successfully undermine the value of the work, your argument will seem more like beating a dead horse than slaying a sacred cow. The conventional narrative arc Malcolm imposes on Stein’s career distorts the facts: neither Tender Buttons, nor Everybody’s Autobiography, fits Malcolm’s overly linear scheme of evolution from difficulty to accessibility. It also causes her to miss the continuity between Stein’s experimental and popular writing, and to overestimate how much we can really “know” a person from a book like the Autobiography, which is as much mythography as it is memoir.

It may be the case, as Malcolm argues, that employing Toklas as her narrator allowed Stein to write a simpler, more accessible book, restoring all the elements of character and plot that were missing from The Making of Americans. Nevertheless, the prose of the Autobiography remains recognizably Steinean; it is best enjoyed after The Making of Americans, because it is, in part, a lighthearted parody of its style. The Autobiography reads like The Making of Americans as if it were watered down for the audience of The New Yorker or The Atlantic, whose editor rushed to serialize the Autobiography after years of rejecting Stein’s work. (In other words, it reads like Hemingway, who helped Toklas prepare The Making of Americans for publication as he worked on The Sun Also Rises.) What is worse, from the perspective of journalistic rather than critical practice, is that Malcolm’s attitude may have affected her access to Katz. In her discussion of Two Lives, Wade plausibly suggests that he was not motivated exclusively by a desire to protect his scoop, as Malcolm believed, but also, as a man who had devoted the better part of his life to making sense of The Making of Americans, by the justified suspicion that Malcolm “was not interested in Stein’s writing, but was seeking a good story.”

Wade, by contrast, states up front that she is “drawn to [Stein’s] work—even if at first [she] didn’t know what to make of it.” This will be familiar to anyone who has started, let alone completed, the supposedly “unreadable” The Making of Americans. But when Wade is confronted by writing she doesn’t understand, curiosity rather than resentment wins the day. As she gets deeper into Stein’s epic, Wade finds herself “hooked by its rhythms” and “eager to follow Stein’s restless sentences as they quest toward conclusion,” an experience she describes as “intoxicating.” Though never credulous toward her notoriously “self-mythologizing” subject, Wade argues that the best way to read Stein is to “trust her.” To read Stein as we have been trained to read Joyce—as a “code to be deciphered”—is “to set oneself up for serious frustration.”

The superiority of Wade’s approach can be measured by the insights into Stein’s work that she gleans from it. “Stein is less a writer in the conventional sense than a philosopher of language,” Wade argues, correctly in my view. Seen from this perspective, the tension between Stein-the-writer’s-writer and Stein-the-bestseller that underpins the conventional narrative of her career simply disappears. What can be emphasized instead is the underlying continuity in Stein’s writing, from the experimental results of “Normal Motor Automatisms,” the medical paper on hysteria and double consciousness she coauthored as a student at Radcliffe in which the style of Three Lives and The Making of Americans is already apparent, to the semi-Platonic typologies of the “writer-scientist” narrator of The Making of Americans, to the literary-cubist poems of Tender Buttons, to the critical essays “Composition as Explanation,” “What Are Master-pieces and Why Are There So Few of Them,” and “Poetry and Grammar,” to the meditations on words and the people who write them that are scattered throughout the Autobiography. From start to finish, Wade writes, “words were her medium and her subject.” To read her, as is often done, as though she herself was her subject is not just to miss something crucial about who she was, it is “to miss the pleasures her work can offer.”

SPEAKING OF JOYCE: he was the writer Stein regarded as her main living rival. She envied the seriousness with which he was taken following the publication and trial of Ulysses. Though the comparison was always meant unfavorably, she took petty pleasure when reviewers said his writing reminded them of hers. Toward the end of her life, she told an interviewer: “You see it is the people who generally smell of the museums who are accepted, and it is the new who are not accepted. That is why James Joyce was accepted and I was not. He leaned toward the past, in my work the newness and difference is fundamental.” This may be sour grapes, but it is not entirely untrue. Pound inadvertently confirmed half the point when he told William Gaddis, then the thirty-three-year-old author of The Recognitions, that “Joyce was an ending, not a beginning.”

Stein’s writing, however, has proven to be a beginning, and an immensely rich one at that. The Making of Americans presents a no less radical challenge to the realist novel’s concept of character than Finnegans Wake, written twenty-eight years later; in this respect, it also predates the formal innovations of Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy by over four decades. The appearances of the Stein character in The Making of Americans, who comments in the first person on the writing of the novel, are an early instance of the now widespread technique of incorporating the process of creation into the created work. With its stripped-down diction and its repetitive, paratactic, run-on sentences, The Making of Americans synthesized minimalism and maximalism long before these two tendencies split to form the stylistic poles of American high literature. More than any other writer, including Joyce and Pound, Stein invented high modernism, and—if you take Fredric Jameson’s word for it—postmodernism, too.

Capturing the whole of Stein’s “cultural afterlife” would require another book, Wade admits, but in “The Branches,” the biography’s penultimate chapter, she provides a “selective snapshot” of it that includes everything from Disney cartoons to avant-garde music and theater to feminist and queer activism and scholarship. Stein was a seminal influence on the two most important postwar movements in American poetry—the New York School and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E—and was claimed as a precursor by groups such as New Narrative and Oulipo as well as individual figures like Eileen Myles, who called her “the world’s biggest influence.” To this list, I’d add two novelists whose remarkable prose styles would be unthinkable without The Making of Americans: Marguerite Young, who bristled at the suggestion that her writing owed anything to Stein, and William Gass, who reveled in the debt.

Stein never shied away from making extravagant claims on her own behalf. “Think of the Bible and Homer, think of Shakespeare and think of me,” she once said. Absurd, to be sure. Yet since 1973, people have gathered in New York to read through the whole of The Making of Americans out loud—not unlike the way Jews gather to read the weekly Torah portion, the way The Iliad was performed at the ancient Olympiads, or the way people attend Shakespeare’s plays. (Or for that matter, with apologies to Stein, the way they celebrate Bloomsday.) This annual tradition, founded by the Fluxus artist Alison Knowles and originally held at the Paula Cooper Gallery, was revived after a short hiatus by the magazine Triple Canopy in 2013. Then, as now, if you wanted a glimpse into the probable future of American letters, you would do better to consult the roster of readers at the marathon event than the longlists of literary prizes.

Stein’s afterlife, in other words, is still shaping and being shaped by the present. Thoughtful and thorough, with insightful interpretations of her work embedded in a compelling narrative of her and Toklas’s life, Wade’s biography makes a convincing case that, while her status as a cultural figure is secure, her writing remains, if anything, underrated. Will Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife be what finally gets The Making of Americans into the wafer-thin pages of the Library of America, or perhaps even trigger a long-overdue Steinaissance? That is the question.

Ryan Ruby is the author of Context Collapse: A Poem Containing a History of Poetry (Seven Stories Press, 2024).