If I love you and I duck it, I die. —James Baldwin

JAMES BALDWIN FELL IN LOVE too easily, and we’re the victors feeding on the spoils of his dysfunctional longings as they mingle with his use of language in the service of divine justice. His private yearning and his public writing, like foils in a great tragedy, fed on him and each other. As he brooded over an unattainable lover—a man married to or beholden to a woman, sharing children and a domestic life with her, while occasionally sneaking off for a charged rendezvous with him—he wrote Another Country or Giovanni’s Room, sublimating his tortured affections with the help of his more demanding obsession, the sharing of ideas so true they had to be disguised as fiction.

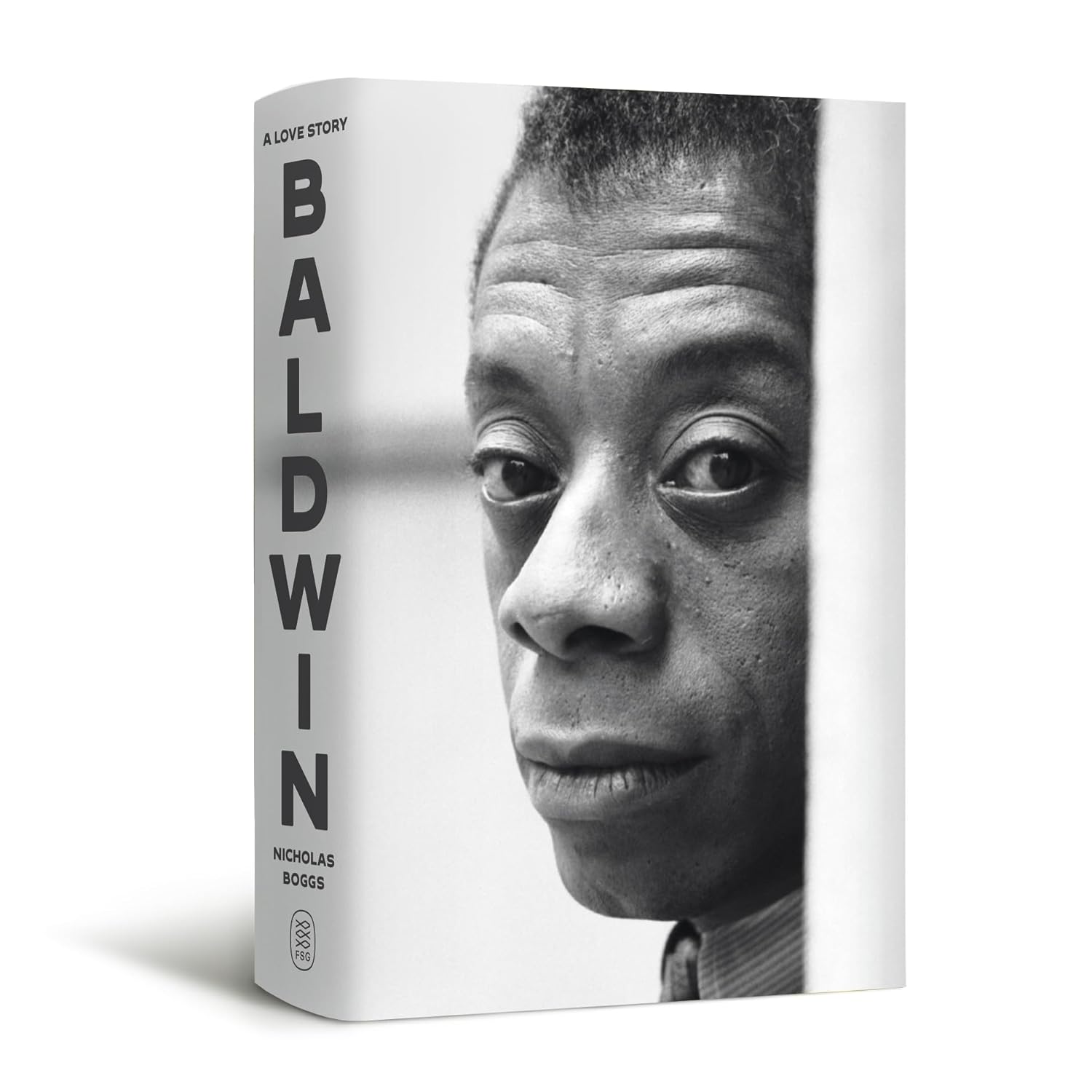

Baldwin: A Love Story, a new biography by Nicholas Boggs, traces one of the twentieth century’s most influential writers and personalities (we should separate the two roles where possible) through his connections with men—those with whom he was in usually-unrequited or half-requited love, and those who were his surrogate fathers and brothers, his chosen family. Boggs mines Jimmy’s personal and often hyper-confessional letters to intimates and friends for clues into his temperament, his secret lives, often discovering histrionic episodes of lovesickness, which Baldwin tended to soothe through professional preoccupations and a self-awareness so keen it cauterized and effaced the self it revealed, inducing periods of relative stoicism and utter despondency. Boggs deems this ability to code-switch seemingly at will an epistolary persona, which it is, along with being another form of intimacy and community building, through letters that point to what could be if we were always open to tender maximalism and divulging in script what we fear uttering aloud. The letters accumulate into a sustained cry for help, one that evokes a void with many faces and personae of its own. When the billets-doux to lovers, family, and friends weren’t detailed recapitulations of his romantic excursions, they were requests for loans or visits. Sometimes they were pitches for films, books, or plays. He didn’t really compartmentalize these areas of his life; in fact he lived in such a way that these spheres became interdependent, his published writings drawing from his unreciprocated desires and vice versa. Happiness in love meant a new book dedicated to its muses, despair meant becoming benefactor to an ungrateful young lover who might become a capricious protagonist in the next novel or essay, on masculinity, or vain protest. Baldwin’s correspondence exists in a fading pre-email and pre-text-message universe, wherein it was common to make an effort to describe and share our lives in complete sentences. Hear the double entendre, the carcerality of the sentence on parchment, its crypt criminality, how it incriminates and unfolds over and beyond a lifetime of speech acts, which become source material for a relitigation of Baldwin now that he’s gone, the parasocial public sphere merging with the secret personae made semipublic record. Elaborate notes signed Love, Jimmy, stamped and mailed, were fantasies, prayers, etiquette, contraband, offering glimpses of the sender that tend to contradict his reputation. Some might say they make him more human; others might find him chaotic and selfish in this fine print, when compared to the self-abnegating sage with all the answers he played on television and in speeches and debates. We might feel betrayed to learn he was more than one man at a time and therefore a lot more like us than the prevailing image of him as one of liberalism’s oracular black mouthpieces suggests.

In one of these handwritten letters, addressed to his younger brother David, Baldwin assessed his own competing tendencies as a mix of helplessness and ruthlessness (implying that both qualities were at least somewhat performative), as if rendering a character sketch of a flawed hero based on himself. He reveals the strategy behind his dialectic when he declares in an interview that he’s candid both publicly and privately so that any attempts to scandalize his name are thwarted—You didn’t tell me, I told you, he taunts an invisible army of his gratuitously scorned critics, preempting those who may try to undermine him and his gifts. He had done this to Richard Wright in “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” And even if Baldwin had been correct to excoriate Wright’s brand of so-called protest fiction as a covert form of minstrelsy, he was aware that the same leveling would threaten him one day. Baldwin would have already told us: he’s ruthless, helplessly so. He was a poet of love, a romantic first, and saw anything less passionate as self-betrayal. Militancy and love had become synonymous by that time, so he had to write his protest songs, his Beale Street,knowing it could be construed as the very sentimentality he was most suspicious of in his youth. He warns anyone hyper-critical of his caprices that what seems like a literary height could be a personal abyss so inescapable, so rooted in another man’s feelings for him, that critics will disappear there with him should they attempt to get to the bottom where they believe his motives live, at the mercy of his muses.

Ain’t no net on that tightrope. Each time out, it’s higher,he shares in an interview with Maya Angelou in response to her question about his need for family support. There, with cameras rolling, he claims his family is the exception, constantly rescuing him. In A Love Story,it becomes clear that there was no sustainable intervention at all, no network of souls to console him if his current lover or infatuation became dismissive or began resisting his advances. He would be found at sea, on a bridge in the pitch black of night, near overdose. Writing was what he did to profess his love for other men, without which it all became meaningless. He was done being the kind of preacher who believed he could save mankind with parables, so the carnal drove stories forward toward the spiritual. It’s almost like he thought maybe those who had rejected him—his biological father whom he never met, his stepfather, the love interests who kept him in abeyance—would finally run toward his embrace and realize their true feelings for him, if he wrote a great enough book. It’s a very disturbing fantasy if you look at it through the lens of his broken heart, but a comforting one if you consider how alienating the process of writing really is; this is how ruthless a great writer must be, selling out everyone, himself included, to get through. It means the torment of the affairs themselves is both real and pantomime, because the writer never quite wants to be invaded by another and merge souls entirely. He needs to hold on to most of himself for the more orgiastic, autoerotic act of love that permeates his lucid literary composition.

When I read some of his letters, it seemed to me that ascetic commitment to his splendid isolation, more than his addiction to romantic interludes and relationships, was the theme haunting Jimmy’s days and threatening to take him and his talent from the world. The talent and the world were at odds, each requiring the level of supernatural attention only he could give them. He really liked it here but also found it unbearable. I like to laugh, and I like people, he once exclaimed, as if in protest to his own shadow. And as with many artists in their darkest days, he could be revived for a while by attention to a new project, stepping off the jagged cliffs that had formed to guard a creative idea’s genesis. And then back onto the brink when that attention proved once again to be a cheap knockoff of the adrenaline supplied in private erotic encounters. Jimmy fell in love too easily but didn’t romance himself enough. He surrendered to men more readily than to his own needs, neglected those needs to chase after or dote on lovers, and inevitably found himself back on the tightrope, pretending at nets or deflecting the groupies and phony supporters who would then become voyeurs to a recurring breakdown that became inextricable from his creative process.

This was a classic case of an artist self-sabotaging in the face of a confounding aura of divine purpose, seeking as much of an out as an in. As Boggs’s book shows, even while Baldwin was under FBI surveillance and punishing public scrutiny, it was his reliance on the distractions of romantic love—a new love that left him intentionally naive and irresponsible, a love that felt like a calling and that competed with and sometimes overshadowed other mandates on his life—that was his number-one menace. You get the sense that he feared his destiny, his success and how lonely it might be, and that impossible love was his scapegoat. Jimmy’s misadventures with closeted or straight men, especially, as a refrain in a life full of unlikely triumph, start to drag on the spirit and feel like some kind of farce, as you read about encounter after encounter. Is it a kink, a reflex, or an involuntary affinity to one involuntary type, made more complex by how taboo open homosexuality was during his youth, and by how he never quite believed in the category, often calling himself bisexual when asked directly. He amplified that ambiguity in the face of homophobia within militant groups, succumbing to tacit peer pressure, and, on rare occasions, like in his interview with Nikki Giovanni, even taking up a minor, cavalier machismo to defend against her complaint that black men save all their sorrow for black women while distributing their high spirits among everyone else.

What do you mean James Baldwin had everything and nothing he wanted, and was forced to stylize his desolation with low-grade gallantry? He is one of our emblems of excellence and making it, but did he really get to enjoy what and who he made? While the lovers and friends were muses, disappointment was his stablest compatriot. Again and again he tried and failed to escape by suicide, and again and again he would recover a love that was a suicide mission, as if maybe he felt guilty for outliving so many of his peers, so many versions of himself. They’re killing all my friends, he cried, and this lament too was seen as style, not taken as literally as he intended it. At the end of nine hundred pages we’ve incurred a litany of rejections adorned in tenderness and loyalty, and a sense that what Baldwin was courting most delicately was the valley where wish fulfillment might have been, the death of Venus like the death of Christ, so that he would be forced to embody sacred, unselfish love, the kind that was really unconditional. This seems to have been his subconscious affliction, this and the artist’s ever-present dilemma, feeling undeserving of real and steadfast gratification, aware of his own ability to betray for a sensation on the wing, to defer his dream lover for the call of the word as he had been deferred for wives or other lovers.

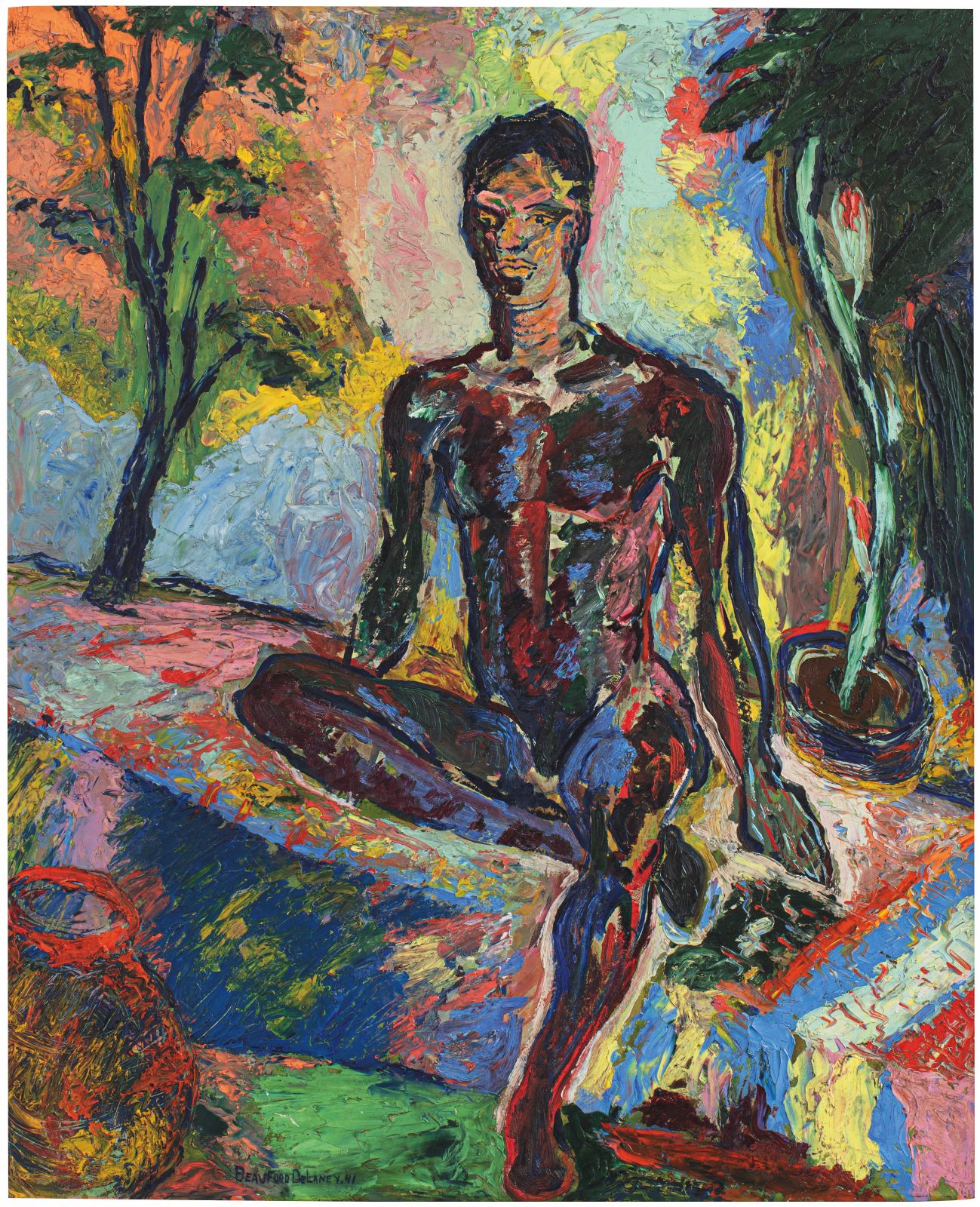

BOGGS ORGANIZES HIS book, like the Bible does with disciples, by the names of Jimmy’s leading men. We get the stepfather (the biological father is glossed over a bit though likely more at the root of the subject’s pathologies than anyone has ever admitted), then we get the painter and surrogate father Beauford Delaney, who takes Jimmy in and shows him bohemian life in Greenwich Village, likely saving him from the fate of his first unspoken love, Eugene Worth, who ends up committing suicide by jumping off the George Washington Bridge two years before Jimmy moves to Paris. We get Lucien Happersberger, his most enduring and complex flame, whom he meets when he flees New York and the ghost of Worth using money, almost all the money, from a small grant. Though Happersberger marries a woman and has a family with her, he later marries Jimmy’s friend and the lead in his play, Diana Sands. And though Happersberger at times seems to envy Jimmy more than he loves him, he is there when he dies, is there when he calls, and the one he looks for in every other man. We get Engin Cezzar, who takes Jimmy to Istanbul, with whom he makes an oath of eternal friendship in blood like grade-school playmates mimicking omertà. Cezzar, another man who marries a woman in the middle of his saga with Jimmy, introduces him to his first biographer, David Adams Leeming, whom Baldwin professes love to in one or two letters, before settling into their platonic alliance. And we get Yoran Cazac, an eccentric painter with whom Jimmy has an affair, though he too is married with children, placing the wife in a semi-consensual love triangle. In between we learn of crushes Jimmy supports even when he can barely support himself, a wished-for fling with actor Billy Dee Williams, and a persistent gnawing sense of seclusion that he soothes with alcohol, which causes him to lash out or become effusive. This was not some avant-garde display of enlightened polyamory; it was an unsustainable way of life in which Jimmy played the role of lady-in-waiting while managing the demands of fame and writing. He sustained it nonetheless with frustrated love, Christ consciousness, and a sense that martyring oneself for a connection is better than no human connection at all.

But there were aftershocks; we learn that Jimmy had two incidents of cardiac arrest in the early ’80s, as if slowly dying of a broken heart. The psychosomatic symptoms evidenced in each affair go unmentioned, tacit assets to the creative process, a fetishized knack for folly and self-abnegation becoming perception at the pitch of passion, catastrophized in novels and essays but not in life itself. I leave the book like leaving one of my fathers’ graves (Jimmy is a spiritual father of mine), feeling soiled, as if I hadn’t brought sufficient flowers and mementos, as if we had decorated his gravestone with totems that now betray him for the sake of these men, situating him as their plaything and ours, yet again a symbol of whatever freedom and vulnerability we extract from his suffering. I find myself believing this is all a case of We tell ourselves stories in order to live.The truth, which cannot be formulated into a story with a beginning, middle, and end, is that fame is a broken heart, and no amount of infatuation, even when it’s reciprocated, can mend that fracture, which attacks the foundation until vipers slip in and sleep there like restive angels awaiting their century.

I have an appointment with the twenty-first century,Baldwin tells one interviewer, less than a decade before his death in 1987. I guess I feel like I’m part of that appointment, and in that way exposed, and in that way lovingly violated by this new evidence. I tried some of the same faux-romantic maneuvers to trick myself out of being here, in the perfect hush of 4 a.m. Los Angeles, ruminating on what Jimmy teaches me by never learning not to love with his whole broken heart. And what I learned, what the book is too deferential to divulge directly, though it shows, is that a man who seems like your soulmate could be your devil, while one who appears to be just a friend could hand you the world. A book you’re afraid to write, like a person you’re afraid to love, will never leave you alone. You’re better off giving in and allowing the story to unfold. All you have to do to survive it is renounce the devil, though you might not be strong enough to do that, and steal the time alone to compose and think and brood and recover. In this way the writer triangulates for a lifetime. Boggs’s book is a meticulous and impressive record of such patterns, a lover’s almanac, and a monument that, in resurrecting a version of Jimmy he kept hidden or glamoured using the other more palatable identity markers, makes his absence more haunting and final, more like justice for him than all our tributes. So much of his time here was spent negotiating between honor and humiliation, between asking for help and being the help, insomuch as a man of letters can do the domestic American Gothic work of cleaning up our messes while his own fester and smolder.

My mind wanders to a letter Nina Simone sent to Jimmy, begging him to reply, to call her, accusing him of leaving her all alone in France while she was there on a comeback tour. I read it in his sealed archives last summer; there was no reply from him. I wonder if he was on tour himself when it arrived and behind on mail, if the letter was intercepted by the FBI to inflict dysfunction among strident voices in the ongoing political movements, if they had been in an argument not documented in the archive, or if Jimmy was chasing after or in the arms of a married, straight, or disinterested man and too absorbed with that relay to tend to his similarly erratic friend. Fame finds a safe harbor in her broken heart, too—a ballad for the romantics who secretly hope to be left alone to yearn and sing and swoon.

Harmony Holiday’s Life of the Party is forthcoming from Semiotext(e).