ALTHOUGH NONE OF HER BOOKS could be said to have happy endings, I have never until now thought of Chris Kraus as a writer of tragedies. As is the case with many of her admirers (and just as many of her detractors), my attention has long been snagged on her work’s thornier, more titillating qualities: how her stories are based very closely on her own life. How she is, unapologetically, an intellectual for whom ideas can be as real and red-blooded as the people who think them up—even if ideas are usually far more fluid and promiscuous. How she writes in the third person, deploying character as a stand-in for herself and others, dissolving the distinctions between author and subject, personhood and persona. These moves, among others, expand Kraus’s literary latitude. Framed as fiction, otherwise stolid fact is charged with metaphoric and symbolic value so that her stories, while told in the mirror, are larger, closer to readers than they may initially appear.

Kraus invented her mode of writing while in a committed—if often alienated—relationship with French theory, philosophy, and contemporary art. Genre—and more particularly, the form and reception of female discourse inside what one might frame as the Heterosexual Project—was one of the knots she tied inside her first book, the beloved and reviled I Love Dick (1997). In its afterword, Joan Hawkins praises it as a work of “theoretical fiction.” In its pages, Sylvère Lotringer (1938–2021), critic, theorist, founder of Semiotext(e), and Kraus’s first husband, describes her approach as “something in between cultural criticism and fiction.” Kraus herself dubbed it “Lonely Girl Phenomenology,” which I always took to mean both the particular consciousness of the craving female writer in isolation, and that which can only be produced by the craving female writer in isolation, apart from outside distractions and satisfactions. Later, in Summer of Hate (2012), her fourth work of what I’ve come to think of as “critical fiction,” Kraus summed up her strategy most legibly and succinctly: “Having no talent for making shit up, she simply reported on her thoughts. . . . She saw no boundaries between feeling and thought, sex and philosophy.” Not that everyone is always on board. As she also notes: “Her work was mostly perceived as a novelty act or dirty joke,” which may explain why, though ardently cerebral, every one of Kraus’s books is a total page-turner.

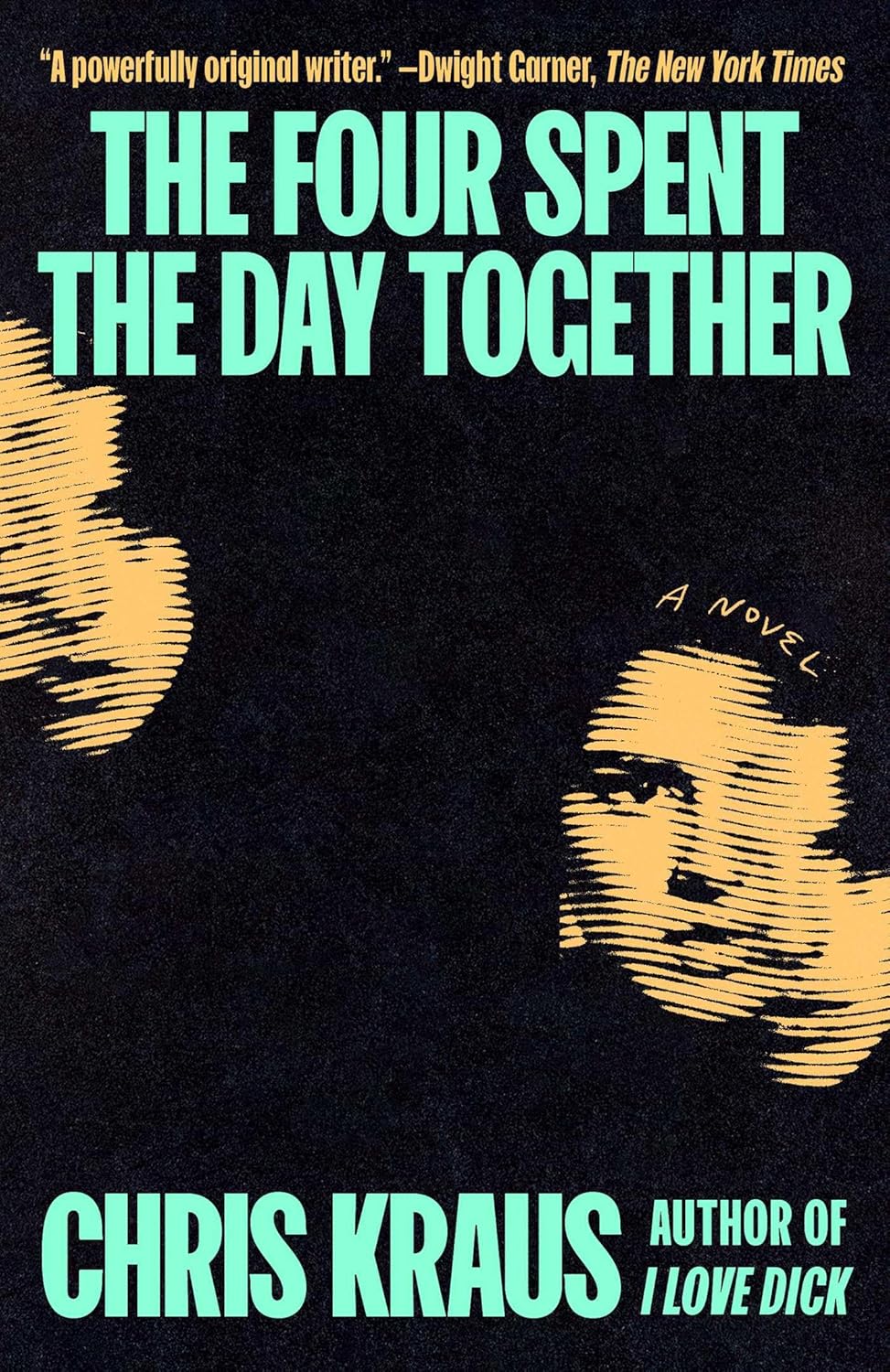

Kraus bends her genre even further in The Four Spent the Day Together, which seems to be her version of a classic American tragedy. It is also her first work of critical fiction since Summer of Hate, which chronicles both the whirlwind romance of Catt Dunlop and Paul Garcia (stand-ins for Kraus and her second husband) and a real estate debacle born of Catt’s blinding idealism and unrelenting belief that she, that any of us, can save another person. Composed of three sections, The Four Spent the Day Together meets Catt (last name now Greene) elsewhere in her life: as a brainy, curious young girl growing up in Milford, Connecticut; as a well-known author struggling to find the time and mind to write while her marriage to Paul, and the world at large, is unraveling; and as she researches a new book idea based on a murder that took place near the home that she and Paul purchased in the small town of Balsam, Minnesota. In previous works, Kraus’s protagonists could be seen as bright-eyed fools, unwittingly stepping into treacheries, or serve as scapegoats so that readers can breathe easier, seeing her fate as strictly of her own making. This is not the case here. The Four Spent the Day Together is relentlessly sad, bleak, offering no comforts of revelation, no high horse to sit on. It is also a dazzling, refined work, formally and otherwise—at once tracking the far-reaching tentacles of addiction, and the trajectory of an almost unrecognizable America, which is spinning out at such an accelerated rate that the capacities for critical thinking, reason, and humanity seem to be flying off its citizens as lightly as ash and dust.

In part one of the book, Kraus introduces her readers to Jasper and Emma Greene, a working-class couple from the Bronx, and their daughters, Catherine and Carla. The Greenes’ American Dream isn’t unusual, and even requisitely humble: to own a home in a nice neighborhood with a good school district and to have what a family needs. However kind and good-natured, the family doesn’t easily fit into Milford’s conservative set. Jasper works all day in the warehouses and offices of New York City publishing houses. Emma feels isolated, too unlike the other mothers. Catherine is bullied by her schoolmates. As she nears her teenage years, she asserts her autonomy by way of self-destruction: smoking, getting high, skipping school, hitchhiking, and exploring her sexuality with men who are young but still too old for her. She changes her name to Catt—her first gesture toward self-authorship—though the kids call her Ugly Catherine, and just when life seems too unbearable, her parents announce that the family is moving to Auckland, New Zealand, where Jasper will begin a new job. The moral of their story, if there is one: sometimes to get ahead in America, you have to leave it behind.

Home is a through line in Kraus’s books: her protagonists are always making one, or buying and renovating and renting one, or selling one. In fact, a belief in the sanctity of home may be about as close as Kraus comes to Family Values. “The first time Catt saw the gray house in Balsam, she was sick with desire,” she writes in the opening line of the book’s second part, jumping in time, and across the world, to northern Minnesota. Catt fell in love with the area when Paul was completing a degree in addiction studies nearby, and she feels the quietude of small-town America will offer both of them a haven from the velocity of their city life: “Twenty eleven, 2012, 2013 were the years in LA when it seemed like everything escalated. . . .Time sped up, a continual stream of cascading events that meant less and moved faster.” And so, with great luck and just enough money, they buy the house in Balsam and split themselves between two homes.

For Catt, Paul is not just a lover but an emblem, proof-in-the-flesh, that there can be recuperation after trauma. She doesn’t use the word “love” much—“Catt believed in Paul passionately”—yet wants very much to help him. As they both understand it, Paul, a recovering addict and convicted felon, is being crushed by a broken system, having to pay for his own drug tests and probation fees and stay sober all while he helps others as an addiction counselor. For various reasons, he loses or quits job after job. Catt may be sympathetic to the stress he’s under—“The pain that he witnessed was infinite”—but readers may find themselves less so. Paul is prone to bouts of rage and depression. “I only ever married you because of your money,” he lashes out at Catt in one of his many dark moods. “You’re old and you’re ugly.” Meanwhile, he begins to drink again.

But who is she to judge? Catt’s mind isn’t wholly her own, either. She spends much of her time online, incessantly checking Facebook, loathing all the humblebraggarts, giving them all too much attention, and somehow acquiescing to the erosion of her intellect: “Reading used to be her great escape, and books her solace. Now she had to force herself to leave the screen and even open one.” Throughout her book, Kraus notes the creeping death drive that seems to fuel compulsive behavior and mourns when and where it wins. (There is another essay to be written on how The Four Spent the Day Together can be read as Kraus’s reply to Avital Ronell’s 1992 landmark book, Crack Wars: Literature, Addiction, Mania, in which she proposes: “Addiction will be our question: a certain type of ‘Being-on-drugs’ that has everything to do with the bad conscience of our era.”) In Los Angeles, Catt receives a panicked phone call one night from her friend Eloise (a fictional version of the late artist Julie Becker). Eloise, who struggles with mental illness and addiction, has just witnessed her boyfriend die of an overdose, then watched as the EMTs bagged up his body and took him away. Catt asks Paul to go to Eloise’s house, thinking he can help her. He sits with her, offers her support. She offers him a joint, then an OxyContin. He takes both. Weeks later, she takes her own life.

In “What I Couldn’t Write,” Kraus’s 2019 essay on Becker, the author recalls the artist telling her: “Thinking, you know, can be completely suicidal. Sometimes it’s better to just zone out.” Kraus herself has dabbled in it. From Summer of Hate, cheekily describing her process when writing about art: Catt “does her ‘best’ work zoning out and writing down words that seem to be draped on the surface of things. She has no idea what they mean.” Zoning out can be the space where consciousness relaxes, temporarily vacates, lets some other part of the brain do the heavy lifting for a while—or not. Coming from Becker, however, the prompt is chilling. The artist asserting thought as a form of death also comes across like a symptom of the self-loathing, the self-immolation, delivered in feel-good packages. Longtime readers of Kraus may take pause at the subtly monumental scene in which Catt and Mikal (Lotringer), her husband of more than two decades, sign their divorce papers. A survivor of the Holocaust, Mikal has always wielded mind over muscle. As Lotringer tells Kraus in their introduction to the 2001 anthology Hatred of Capitalism: A Semiotext(e) Reader: “I wanted theory to become ideas, that would have a direct impact. That would be grasped as naturally as you breathe . . . Documents, images, quotes, ideas being part of some kind of movement that takes you from one thing to the next, and changes everything about the world.” Mikal’s exit marks Catt’s freedom to marry Paul; it also signals the end of this kind of intellectual presence in her life.

Kraus’s critical fiction does not veil and protect. More often than not, she deploys herself and others with wit, candor, and compassion, yes, but does not shy away from indictment, allowing Chris or Sylvie or Catt—or whatever she names her protagonists—their fumbles and shortcomings, negligence, and shadow sides. After all, there is no freedom of choice without the freedom to make a bad choice. In her books, Kraus inhabits, and writes within, a gray zone, in which moral clarity, moral certitude, is unavailable, made impossible simply by the circumstances of being human: an offer of help is extended on the presumption that someone needs it, wants it; an offer of care perhaps overestimates one’s healing powers. This is not to say such gestures are wrong, but neither are they purely beneficent. The same idealism that led Catt to try to create affordable housing in Summer of Hate also opens her up to public derision. After a colleague notorious for spewing venom like a geyser drunkenly jokes to a young critic that Catt is “a landlord, not a writer,” the young critic tweets this line. Soon Catt is fodder for an online burning by, among other people, an ex-student, a PhD candidate at Berkeley, and a poet: “Catt Greene put the first stone in Virginia Woolf’s coat . . . & turned on Sylvia’s oven”; “I’m tired of radical white feminism that mostly ignores questions of race”; “I mean I was literally reading Sebald’s Natural History of Destruction until seconds ago and this is a far more damning indictment of all humanity, well done CG!”

While it’s no revelation that humans can be cruel, it is always striking to note how we perceive our cruelties as correct, even just. If we have learned anything from the attempted atomization of fascism into our every social, political, and cultural pore, it is that none of us can trust that we are more virtuous than the forms we use—whether autofiction, platform, or post. What an optimist might call constraints, an optimist of a different stripe might call complicities. Catt isn’t brutalized by yawping, trigger-happy right-wingers; her trolls are would-be artists, writers, devotees of the life of the mind who might otherwise understand that mirroring power (and its forms) doubles rather than shatters it. But as Mikal liked to say: “It’s not enough . . . to be merely intelligent.” Kraus-as-Catt also faces the fact that her words, like her peers, are fair-weather, too, and despairs when she realizes that neither the initial failure nor the present success of I Love Dick has had much to do with the novel she believed she put into the world. “Since Trump’s election and the Twitterization of everything, she’d started to wonder if there was even a point to writing books anymore. And who for?”

In the midst of her ongoing character assassination, Catt’s attention is diverted by a gruesome, front-page article in the local Minnesota newspapers: a thirty-three-year-old man named Brandon Halbach was discovered dead, shot twice in the face, in the snow on the Nagamo Trail not far from where Catt and Paul live. The three people arrested for the murder—Brittney Linn Moran, Evan Stanton, and Micah Waldon—are seventeen, eighteen, and twenty years old, respectively. Kraus, as always, changes the names of those involved in the crime, which in fact took place in 2019 on the Mesabi Trail outside Hibbing, Minnesota, best known as Bob Dylan’s hometown. (In what might be considered her book’s denouement, Kraus’s research of the case is presented as part of a joint exhibition with artist Juliana Halpert titled Civil Commitment, which is on view through October 11, 2025, at Bel Ami gallery in Los Angeles.) Catt notes that there is story missing from the story—

According to [Stanton], the four spent the day together and Waldon, who carried a gun, talked of a plan to kill Halbach in retaliation for unwanted sexual advances and inappropriate touching of Moran, who was his girlfriend.

—and is moved to find out what happened that day, to understand who these people are and what they did and said to one another that led to the killing. Now that she’s been made an enemy, her books and ideas mangled and misunderstood, she thinks it might be best to write something that isn’t centered on her own life. Paul is excited by the idea of Catt pivoting to true crime, but she sees her task, her genre, differently: “She thought about the distances between LA and the gray house in Balsam and the lives of these four young people on the Iron Range and decided she would try and bridge them,” Kraus writes, forecasting the book now in her reader’s hands.

The stories of Brittney, Evan, Micah, and Brandon are heartrending, harrowing, not unfamiliar, and certainly not singular. All were raised in near poverty and abuse by parents who were raised in the same. Their families, their small towns, were destroyed generations ago by capitalism’s ruthless boom-and-bust playbook. Then meth descended and people in the long-dead economy could suddenly access the feeling of speed. The internet and social media also descended, and people could more or less do the same. These addictions irrevocably changed the Iron Range. “There’s a new norm out there, a norm you and I wouldn’t recognize,” a man called Landlord Mike tells Catt when she asks his opinion about the Nagamo Trail murder. “Their thinking ability, how they perceive life—it’s kind of depraved.” It also has its own terrible logic. As Micah—whose defense claims he pulled the trigger to defend Brittney’s honor—tells the courtroom on the day of his sentencing: “I don’t really know what to say other than I’m a man that was raised on my principles and morals. And what I did was bad but at the time what I thought I was doing was right.”

As Catt researches the murder, Paul sinks deeper into addiction, years of spiraling having sucked too much of the light out of him. The book’s final wallop is unexpected, delivered by Kraus/Catt with a cool, open hand. In these pages, she quotes from a letter that Evan, who took the victim’s car, sent her from prison, giving his account of what happened. Strangely, he writes in the third person, putting his own name in scare quotes: “So yes ‘Evan’ was going to bring the car to Brainerd but at the time ‘Evan’ had no cash and nobody to follow him and everything that was happening was just going fast.” And before the reader has time to take note of what it might mean that the velocity of contemporary life feels the same as the velocity of a crime—or reflect why this particular writer would put some distance between himself and his story—Evan offers up an unsettling insight as to why he just didn’t stop the murder: “I think he was looking toward the future.”

Jennifer Krasinski is a writer, critic, and an editor at Bidoun.