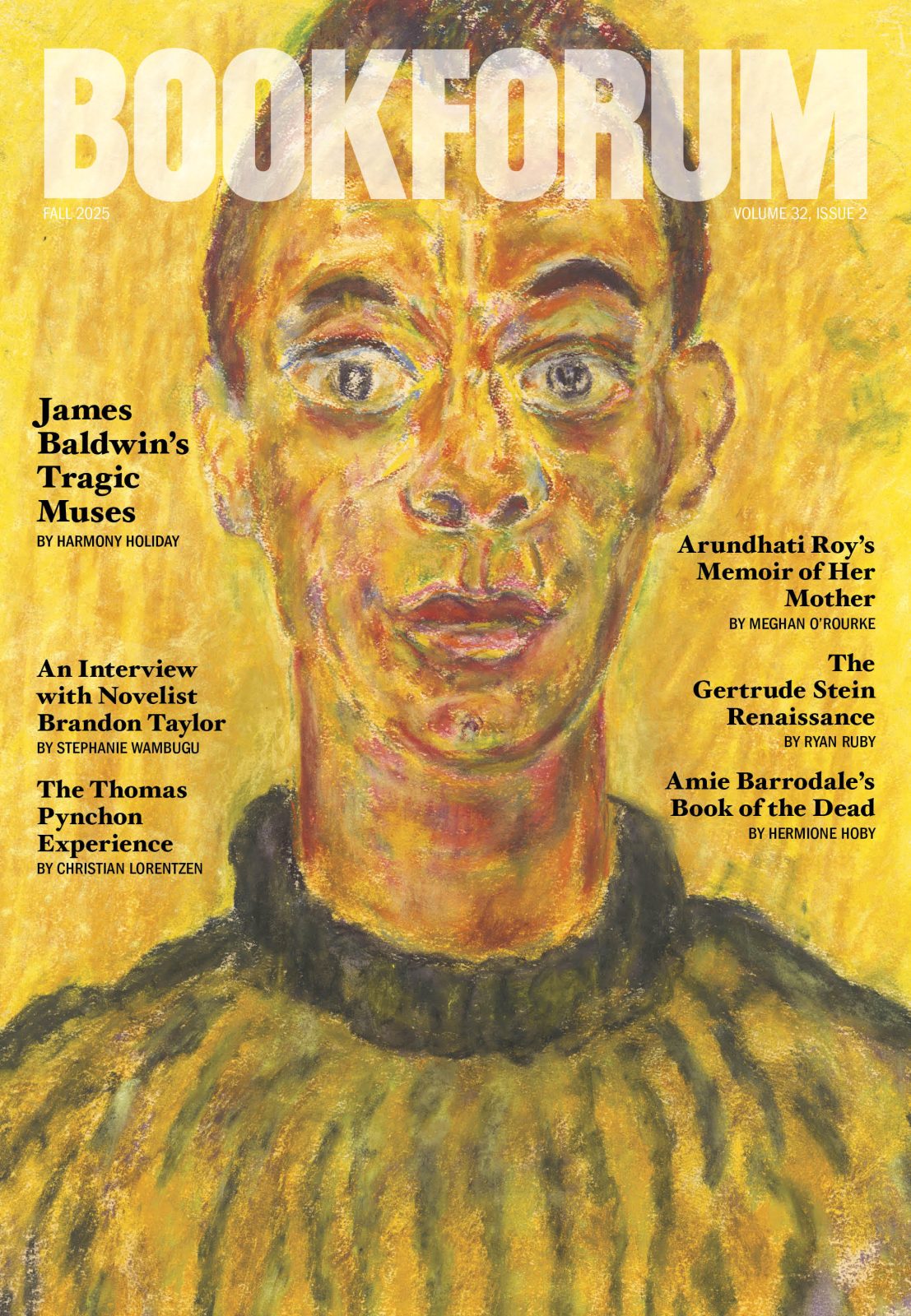

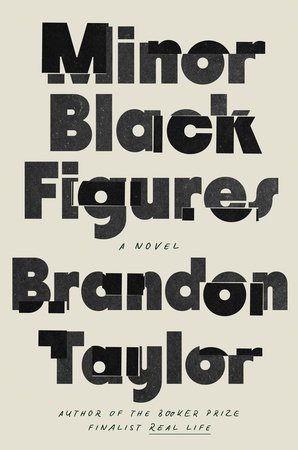

Brandon Taylor’s Minor Black Figures (Riverhead, $29)—his fourth book of fiction—is an ambitious departure from his previous work. The novel takes up timely and fraught questions of representation within a culture industry hostile to idiosyncratic depictions of Black life that do not adhere to predictable narratives. At turns satirical and humane, the novel follows the romantic relationship of an unlikely pair: Wyeth, a painter, and Keating, a former Jesuit seminarian who meet sharing a cigarette after an opening for a group show of artists who traffic in the kind of identitarian and didactic art the novel is not interested in replicating. In his first novel set in New York City, Taylor meditates on careerism, self-exploitation, uniquely American racial tropes, living digitally, and post-pandemic existence. I recently sat down with him at Metrograph Commissary to discuss his influences, his criticism, Émile Zola, what insights about contemporary life can be gleaned from the great television writers like Lena Dunham and Shonda Rhimes, the impermanence of the Internet, and more.

STEPHANIE WAMBUGU: Minor Black Figures is the fourth book you have published and your third novel. How would you say your concerns as an author have changed over the past five years? How is Minor Black Figures a departure from previous work?

BRANDON TAYLOR: Initially, I wanted to write myself into literature. Now I’m more interested in the relationship between the individual and society, and my books have become more porous to the concerns of the world. My first books are about characters who don’t know how to articulate their feelings while my more recent ones are about characters grappling with real-world problems. So Minor Black Figures is a departure in a number of ways. It’s set in New York—my first book not set in the Midwest. It’s my first book about a character who isn’t in grad school or even thinking about grad school. I also had the most ambitions for it in terms of scale: I wanted it to take on large social questions and issues. And so this book not only happens in a specific place but it also unfolds during a specific time in America. My other books are kind of amorphous as to the when and the where.

WAMBUGU: The backdrop of the art world and the subject of figurative art feels like an especially fitting allegory for what you’re dealing with, how painters might metabolize contemporary events in a way that’s different from novelists because a painter can work more quickly. I’m thinking of this quote in the book where you say, “Black figurative painters have to wrangle with both subjectification and objectification.” Do you see writing realist fiction as presenting a similar formal challenge, of being both the subject and potentially the object to a reader?

TAYLOR: That’s a great question. I certainly feel those challenges in my own life and work. In talking to painters—and even playwrights—I found that they feel quite activated by the challenge of representing the personal through the lens of the social. Their work seems much more responsive and on the quick of social issues. Sometimes novelists have an intense almost terror of letting the social in or dealing with the world or being inspired by real events. As a realist trained in a very particular strain of American literary fiction, I felt that and had a lot to work through. I realized that at bottom I had a question: How can one write about Black lives and Black characters, as individuals, when so much of the experience of being a Black person in America is being made abstract by these larger systems? So it becomes a question of how you make that legible to a reader. Because the characters I’m writing are Black, they are deeply aware of their existence as an abstraction in the racial imaginary that runs this country while they’re also having individual life experiences and individual moments. But if you acknowledge that, you’re accused of playing to race.

WAMBUGU: Of being didactic.

TAYLOR: Yes, of being didactic. And if you ignore it, you’re writing a fable.

WAMBUGU: Right. It’s a fiction in more ways than one.

TAYLOR: Yes, exactly. I find that really difficult but also really funny. It’s kind of comic to be in a double bind where there’s no right answer. So I decided to make it part of the comedy of the book.

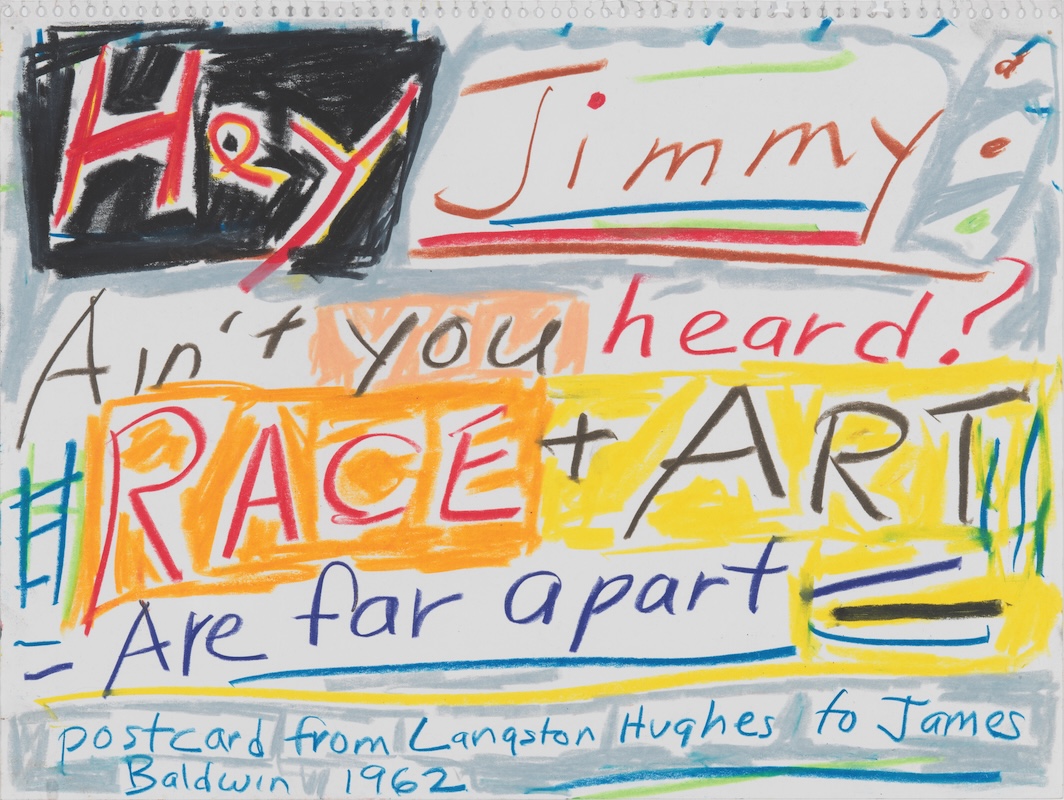

WAMBUGU: The painter Stanley Whitney made a drawing of a letter Langston Hughes wrote to James Baldwin because Baldwin had a similar charge against Hughes’s work being too didactic and being too interested in race. The letter, and in Whitney’s drawing, reads, “Hey Jimmy: ain’t you heard? Race + Art are far apart.”

Speaking specifically about social realism in the United States, I see your books as being very situated within the United States in terms of their content and setting. But I remember you saying that they’re better received in Europe. You draw a lot from European writers—I’m thinking particularly of Zola and your essay about the experience of reading his body of work in its entirety. I was wondering how you feel your work is read differently outside of the US. How do other audiences engage with it?

TAYLOR: My last novel, The Late Americans, was published here and in France and Britain. Here in the US, some reviewers took exception to the fact that I was writing in a very quote-unquote literary voice, that I was trying too hard to sound literary or whatever. I think maybe only one or two of the reviews mentioned Zola or realism at all. Whereas in France almost every review mentioned Zola. They mentioned realism and they understood the lineage in which I saw myself. I think maybe it’s the case that those writers are more alive to the culture, and they see the reference. In America, it’s not read so clearly in my work and maybe that has to do with the retreat of American realism from the forefront of popular culture.

If you read the progression of American literary fiction as being from Carmen Maria Machado to George Saunders, from Saunders to Ben Lerner to Teju Cole and, to throw in a couple of European writers, Rachel Cusk and Knausgaard, then my work might seem kind of weird. If you view American realism as a story going from the sort of antic fables of Saunders and culminating in this very cool authorial autofiction, then my work is kind of out of phase and out of step. I think that people here just don’t know how to read the antecedents, while a European audience can see who I’m clearly influenced by. The average American critic isn’t going to reach for Henry James, they’re going to reach for whatever other three Black authors are available to them. For most of them, it’s going to be Percival Everett or John Edgar Wideman, and I don’t bear any resemblance to those authors. And so the critic is like, What is this guy doing?

WAMBUGU: Sure, they’re much more interested in ethnicity than a literary lineage. In terms of lineage, I wonder how you situate yourself in this tradition of critic-novelists. I’m curious if you feel like there are any predecessors who were working in both modes who you feel like you’re inheriting a tradition from. And more generally, how do you see the relationship between your criticism and fiction? How do you think this influences how your work is read?

TAYLOR: I’m honored that you think I’m a critic-novelist—I consider myself such a baby critic. It used to be much more common, especially in the nineteenth century, where I’ve done too much reading in the last couple of years. It used to just be the way it was: writers would feel that they had to write a manifesto in order to justify the kind of fiction they wanted to write. Into the twentieth century, Virginia Woolf—who I consider an idol and an icon—and even James Joyce wrote really wonderful criticism. If you look back to some of the early works of Edgar Allan Poe, he was known mostly in America as a critic. They didn’t love his fiction at all—he was much more beloved for his fiction abroad. To me, they’ve always been together in the writers that I was reading. So if I’m looking at people who I most identify with, then I would say Baldwin of course and Woolf certainly. And weirdly enough, George Eliot is kind of my idol in all things because she was so strict with herself, with her standards, and she sort of invented realism in the Anglophone world with a number of essays that she wrote on realist art. Writing criticism helps me clarify for myself certain of my motives; it generates interesting artistic questions that I try to take up in my own work. And it provides more tools for discernment. But for me it’s all just an exercise in clarifying my thoughts, whether it’s writing a short story or a critical essay.

WAMBUGU: Moving more into the plot of Minor Black Figures, I’m curious about the distinction you make between careerism and someone who has a “true” vocation and a “real” calling. The book contains a group of careerist artists who are making a certain kind of diasporic work that you’ve created a shorthand for—they’re called MangoWave. Their work is self-exploitative and tends to pander to liberal art world audiences. And then the character Wyeth seems to really grapple with why he’s making the work he’s making and really agonize over the legitimacy of his subject matter. I was wondering if it’s a distinction you feel is worth making in life or if it even can be made?

TAYLOR: Yeah, I mean, “Can it be made?” is a great question. Maybe we will discover that together. Maybe that is the sort of question you have to live your whole life to come to an answer. But I felt that tension really acutely with The Late Americans. I had written a complete draft of it, and I had this feeling that it just wasn’t quite right. My editor kept telling me, “This is a beautiful book. You’ve never written better. Your writing is so great. It feels like the book is done.” But I kept thinking, Is beauty sufficient? Does the world need this book? It was a question prompted by this kind of icky thing. When I announced the book, this critic shared the screenshot of my book announcement and said, “Do we need another one of these books, eww.” It planted the question in my psyche. What is the reason a book should exist? What is the motivation to publish a book? If someone else were to ask me whether the fact that they wanted to publish was a good enough reason, I would say, yeah, of course. For myself, I was like, sure, it’s a good enough reason, but do I want to publish it for the right reasons? I would sort of endlessly spiral about it, and I eventually got to a good place with that book. But before I wrote this book, I basically killed another book that I’d been working on for five years because it just didn’t feel right. And again, my editor told me, “This book is sharp. It’s really interesting. Language is great. I want to read more of this.” It made me realize that the writing is good, so the reason that I’ve struggled is that I just don’t want to write it.

WAMBUGU: Right. Proficiency is not enough if you know that you’re proficient.

TAYLOR: Exactly. I was just like, “I need to find another reason to write a different book.” I set that book aside, did my teaching, and then I checked myself into a hotel for eleven days and wrote the first hundred pages of Minor Black Figures. And I discovered I wanted to write this book. I wanted to take on all of these questions, like how do you know that you’re making art for the right reasons, or is it fair that as a Black person I’ve got a different set of questions? I’ve got a different set of hills I gotta climb. How do I know that what I think is what I think and it hasn’t been implanted in me by the mind virus? I felt like I had never read a book that stared into the face of the race question for the Black artist in a way that wasn’t tacky or cheesy.

WAMBUGU: I wanted to ask you about Wyeth. He’s not religious, but he had a religious upbringing with a grandfather who’s a lay preacher. He has a roundabout relationship to his faith and says that we’re all trying to deal with the fact that life without religion or a vocation is arid. There’s some sort of loss that accompanies the loss of religion. Wyeth falls in love with a man who wanted to become a priest then left his studies in a seminary. I see certain parallels between being a member of the clergy and being an artist. I was wondering if you could talk about the role of vocation or the role of being called in the book.

TAYLOR: Yeah, this idea of being called is one that I’ve found fascinating for so long. You live your life and then you feel this compulsion; it’s true of the clergy, but it’s also true of art. I view them as very much the same thing—there’s a thing that you’re meant to do. There are all those stories of prodigies who sit down at the piano and know from that moment that this is the thing for them. For me, it’s really interesting because I grew up very Baptist. In this milieu, everything was structured by religion. Even though I’m an atheist, everything gets organized around this idea. And so for me the notion of a call has been with me my entire life, but how do you fit that into a secular world? In a world where you are an atheist, do you still believe in a call? If so, who is doing the calling? How does it function in the life of people who view themselves as atheists or irreligious or nonbelievers? What does that belief system look like in a world that is so compartmentalized and that has been so evacuated of meaningful connection by capitalism and by the way we live? Minor Black Figures dramatizes the fate of the call in a society where doing anything with meaning is made increasingly difficult by the structures that prevent people from connecting or even hearing their own interiority or knowing themselves or knowing their motivations. And so a person who is called would seem like an incredibly irrational person.

WAMBUGU: Yeah, even priests and artists have to think about whether or not their work is lucrative.

TAYLOR: Yes. Exactly. And they sort of trudge on, right? The fact that artists continue making art even though it’s not going to make them any money—those people are viewed as nuts by increasing sections of the population. I think about every kid who tells their parents that they want to be a DJ—it’s a trope or a meme at this point or kids who want to be English majors. As society becomes increasingly optimized, people who are called to do things that don’t align with society’s values seem mad. That’s been the case for the longest time—prophets and fools are the same people. And so I was interested in what a prophet looks like in a world that is being evacuated of belief or meaning. What does the call look like? What happens when someone who was raised religious but considers themselves a-religious confronts the fact that the person across from them actually believes. Are they insane?

WAMBUGU: There’s an Italian director who left Catholicism, and said that in lieu of the church, he turned to cinema. This interview is taking place in a movie theater, and Metrograph is mentioned in your book. There are many allusions to filmmakers in the novel. Wyeth paints Black figures into scenes from directors like Bergman and Pasolini and Fellini and Rohmer. I was wondering what you feel cinema gives to you in terms of narrative possibilities. Also, do you have a favorite film?

TAYLOR: I adore this question. I love movies so much and when I was writing my very first short story, I was trying to evoke the feeling of queer melancholy that’s in this film Weekend by Andrew Haigh. So many of my early short stories were about sad, depressed, gay French boys. Cinema gave me this vocabulary of how people move in space and how you can evoke a feeling without naming it directly. I fell in love with quiet movies even before I fell in love with so-called quiet literature. Film from the very beginning had such an overdetermining impact on my aesthetic. I spent a long summer watching every Rohmer movie, all of Bergman’s movies, and watching this film Bergman Island, which had all this great metacommentary. For me, cinema is so good at evoking structures of feeling and conveying things without saying them. And it’s so good at articulating all the stuff I love in relationships—the deep subtext of a character’s gesture that means so much because of the accumulated history in the relationship that has occurred across the breadth of the film. It’s such a beautiful almost poetic form of storytelling that I’m always trying to evoke with my writing. Part of why I wanted to write this book was because I wanted to describe scenes from movies I really love. I had written two other books—that may or may never see the light of day—in which I set myself a task of writing with quite a limited palette. This book is a gift to myself after two very astringent, very intense books. So it’s full of movies I love and full of paintings I love and writing about painting, which is another vice of mine—I love writing about art. The fact that it’s in there has everything to do with excess, just delighting in it.

WAMBUGU: It’s pleasurable for the reader as well. I was going to ask about the pleasure that the characters allow themselves in this book as opposed to previous books. I was so taken by the way one character in Real Life describes a sexual encounter as “a small blow job in the dark.” I found that so funny. It was an immediate disavowal of an incredibly significant sexual encounter. I was wondering if you would say a bit about your approach to writing sex and its transformation over the course of your four books.

TAYLOR: Thank you so much for saying that—I feel very seen. I often get asked what order people should read the books in. I always tell people to read them in publication order because if you do, it reads like someone discovering the possibility of human connection. The books get much warmer as they go because I think I became much less pessimistic about the notion of human connection. In the first couple of books, especially, sex is there but it’s so violent and I think it’s because I was deeply suspicious of pleasure and of narratives of pleasure. I grew up very Baptist—or very Protestant—so pleasure is always very suspicious to me and my people. The emotions in those books are so intense and so severe. And with this book, I honestly just wanted to write about a guy whose problems are no less intense than in the previous books, but who’s just a lot calmer. He’s been through the most intense firing of his soul, and made it through to the other side. There’s a character who comes back from one of the earlier books because I felt he’d been quite done hard by. And so I wanted to bring him back and see what more I had to offer a character in this new phase of his life. I love romance and I love love and I wanted to put some of that in my books. I’d never let myself do that before.

They don’t suffer as much as they maybe did in previous books, and if there is a trauma plot, it has a lighter touch.

WAMBUGU: I think that there is something about the way contemporary life is revealed in your dialogue. People reading your work in the future would have a sense of the concerns of our day or the way that people live now. A lot of the characters, even the friends, insult one another in a way that feels so understanding and comes from a shared language or idiom. I was wondering how you arrived at your dialogue, whether you borrow from life, and if there are other writers whose dialogue you’re particularly drawn to?

TAYLOR: That’s such a wonderful compliment. I’ve had a journey with dialogue. When I was in graduate school, my dialogue was something many of my classmates didn’t like in my work. They would say things like, “I just feel like these characters have a relationship that we the reader aren’t privy to.” And I’d always think, Well, yes, correct . . .

WAMBUGU: You don’t know them.

TAYLOR: Isn’t that good? They’d always be like, “I feel like I’m spying on a conversation between two people . . .”

WAMBUGU: That’s ideal.

TAYLOR: I always felt like that was the goal or the ambition. I think a lot of people writing dialogue these days get really anxious about the exposition part of it, so they write these banal non-conversations. It is so funny to me because even though this feels like such a contemporary issue, if you go back and you read György Lukács writing in the 1930s, he also complains about it in “The Intellectual Physiognomy of Characterization.” This has been with us a long time. For me, my sort of epiphany for dialogue came from watching Girls.

WAMBUGU: That’s sacred to me.

TAYLOR: It’s a sacred text. That show is so important to me for so many reasons—also Shonda Rhimes is one of our great stylists in terms of dialogue. Do not get me started on my unified theory of Shonda Rhimes dialogue. What both Lena Dunham and Shonda Rhimes understand is that you can’t be afraid to be melodramatic. You can’t be afraid to be direct or obvious. Sometimes your character has to say the thing, and you have to use your ear to shape it. You have to use your dramatic sensibility to make that expression land in a way that feels authentic to the moment. That is the work of the writer. I couldn’t be writing these little subtle things where a character says, “Hey . . . ”

WAMBUGU: Or a character who says: “And yeah . . . ”

TAYLOR: “And yeah . . . ” Unless I was doing it for a deliberate effect. It just freed me up to let the character be a mess in their dialogue and use my ear to make it feel natural to the moment it’s in. But yeah, Shonda Rhimes, she’s my mother, she taught me so much.

WAMBUGU: And life is so much more dramatic than we’re willing to admit while writing. That’s why we gossip.

TAYLOR: I was just texting a friend about the Jeffrey Epstein letters being published. The Times posted pictures of the inside of his house and wrote a piece about it. One of the details is that he had a signed first-edition copy of . . .

WAMBUGU: Lolita, no?

TAYLOR: Of Lolita!

WAMBUGU: If you put it in a novel, people would accuse you of being too on the nose. There’s the Mark Twain thing where it’s like the problem with fiction is that life can be true, but fiction can’t be. Did you see the birthday card that Donald Trump sent Epstein that said, “May every day be another wonderful secret”? This is the stuff you couldn’t put in a novel, but then people like Pynchon and DeLillo do put it in novels and people respect it.

TAYLOR: It’s because they understand melodrama. They understand the essential force of melodrama and one of our great melodramatics is Toni Morrison. People are always writing these treatises on “What is ailing contemporary fiction.” It’s because everybody wants to be cool.

WAMBUGU: Yeah, everyone’s anhedonic, and doesn’t feel anything. Do you know Stanley Crouch’s essay about Beloved where he says it’s far too sentimental? I remember thinking, How could you write that book without veering into potentially being sentimental? It’s worth the risk to me, and I think there’s something vital about fiction when you allow yourself to be fairly sentimental.

On another note, I wanted to talk about your character Dell Woods. He’s an artist who fades into obscurity, and Wyeth goes on a search to find out what happened to this man. You write that, “Sometimes they came across art by people who had vanished, history was filled with such cases. In fact, most of the people who had ever lived had died without a trace. Recent history, meaning the internet, had given them all the idea that anything and anyone could be tracked and named and sorted.” And you conclude with the idea that “the internet was not forever. It was simply very big.” What I love about that passage is that it works in two registers. It can have this serious digressive bit and then also kind of tell a joke. I’m curious how you metabolize something as impermanent as the internet and this excess of information that we’re all getting. You’re writing in a form that ideally is enduring and will outlive you—the novel. And you’re writing about something that’s fairly impermanent and can often be very frivolous—the internet. I wonder how you square those two things away.

TAYLOR: You asked me earlier about how this book is a departure, and it just now occurs to me that it’s also a departure in that it’s my first book where the internet is doing weird plot stuff and plot shenanigans. Writing this book I thought I couldn’t ignore the internet, because that’s not realistic. In my other three books, I wanted to create a partition between the internet and the eternal themes I wanted to write about. Whereas with this book I felt like I maybe don’t know how to write about the internet in a grand sweeping way, but I now know how to write about someone’s research practice. The internet is showing up in the work in ways that I recognize mainly because I’m learning how to do it. Novelists have to learn how to write about the world that they’re in and write about it in a way that doesn’t sicken them or bore them. They can’t ignore it because to ignore it is to sort of make your work increasingly detached from the material and spiritual conditions of your life. For me, the key is not trying to capture the whole grand image of the thing. But capture it in the little ways that it shows up in our lives. The character checks his phone and sees that a bad review has gone viral. There’s a group of artists, his contemporaries, that he’s in a memetic self-hating thing about. So yeah, he’s going to check their feed and now he’s got to research this lost artist. How does that look? So the internet shows up not as a grand abstraction but in these really concrete ways. As an artist, I’m interested in the concrete. I’m interested in the ways, the small ways, that the grand thing shows up.

WAMBUGU: In terms of this question about impermanence and posterity that the internet raises, I want to ask what you want people in the future to know about Minor Black Figures or about Brandon Taylor?

TAYLOR: Hopefully when they read it, they’ll know a little something of what life was like in about a ten-block square radius in Manhattan. I hope that the reader will be rooting for this pair, this couple that sort of bumbles through a steamy summer.

Stephanie Wambugu is the author of Lonely Crowds (Little, Brown, 2025).